The Economic Strain on the Church

Legal liabilities from the sex scandal threaten a U.S. Catholic Church

already beset by systemic financial problems

By William C. Symonds

Business Week

April 15, 2004

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_15/b3778001.htm

See also the related articles in the same issue of Business Week:

The

U.S. Catholic Church: How It Works and Q&A:

A Talk with the Vatican's Moneyman.

As the U.S. Catholic Church battles the most sordid scandal in its history,

it is fighting to preserve its moral and spiritual authority as the largest

nongovernmental institution in American life. Yet even as it does so,

another catastrophe looms--one that is not about sex abuse and priests

but about money and management. The fierce scrutiny that is piercing the

Church's veil of secrecy over sex is also beginning to reveal the largely

hidden state of its finances. As the institution's legal and moral crisis

builds, so too do the threats to its economic foundation--a foundation

already under enormous strain. "If there is anything that is kept

more secret in the Church than sex, it is finance," says former priest

and activist A.W. Richard Sipe.

|

The cascade of legal claims may just be starting. Plaintiffs' lawyers say as much as $1 billion in settlements, many of them secret, has already been paid since the first big sex-abuse case surfaced in Louisiana in 1985. And more payouts, sparked by incensed juries, are likely in the future. Cases filed to date "are just the tip of the iceberg, and it will be a multibillion-dollar problem before it ends," says Roderick MacLeish Jr., a Boston attorney who has represented more than 100 victims in the past decade. Church attorneys dismiss such sums as exaggerated. But they concede that because much of its insurance is either inadequate or exhausted, the Church increasingly will be forced to sell land and other assets to pay claims. Ultimately, some dioceses "might be pushed into bankruptcy," warns Patrick Schiltz, dean at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in St. Paul.

In turn, that poses a growing threat to the myriad good works the Church performs in its vast network of schools, colleges, hospitals, and charities. If the scandal cuts into donations, as many fear, "that would create a whole new class of victims--the kids in our inner cities," worries David W. Smith, director of finance for the Archdiocese of Boston.

Most appalling to many Catholics has been the insensitive way Church officials have handled the crisis, putting the protection of well over 1,000 of its priests above the interests of the victims. On a scale of 1 to 10, "this is an 11," says former Hill & Knowlton Chairman Robert L. Dilenschneider, who has helped manage such crises as Three Mile Island. "The Church has been hit by a truck and permitted the truck to back over it several times," he says. "The quickest way to deal with a crisis is to tell it all and tell it fast." Instead, the Church's hierarchy helped fuel the crisis by dealing with abusive priests in-house, often reassigning them to new parishes, and by insisting that victims sign confidentiality agreements before receiving settlements.

Now, a groundswell is building for radical reforms--among them optional celibacy, changes in the strict dogma about sex, and the ordination of women. At the same time, there is a growing call for more financial disclosure and corporate-style discipline for the billions on the Church's books. "The Church consists of the people, so the people ought to know what is going on," says William B. Friend, Bishop of the Diocese of Shreveport, La., who worked in banking before becoming a priest.

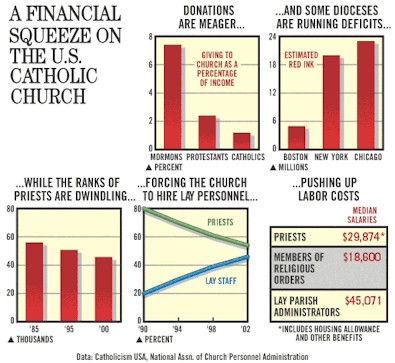

Indeed, because the Church depends nearly entirely on contributions from parishioners, experts say such reforms are necessary before donors will be assured that the practice of covering up sex-suit settlements funded with the collection plate has ended. Already, Catholics give half as much as Protestants as a percentage of income. And a Mar. 27 Gallup poll found that 30% of Catholics are now thinking of cutting off contributions.

To regain parishioners' confidence, the Church should start acting like a corporation, says R. Scott Appleby, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism at Notre Dame. "The way to restore integrity," he argues, "is to become perfectly transparent financially, to submit financial reports, and to become exemplary in best practices." If you do this, adds Bishop Friend, "the money comes in."

The Church can ill afford diminished contributions, operating as it does on donations. A common perception of the Church is that it is an ancient treasure chest with deep pockets, replete with opulent basilicas, a world-class art collection, and trophy properties like New York's St. Patrick's Cathedral. Yet the glittering holdings and the enormous reach of its institutions mask serious, systemic operating problems.

For one thing, there is a startling lack of financial controls and oversight--an omission that experts say has allowed bishops from California to Philadelphia to misuse Church funds. What's astounding to some is that even though billions of dollars are at stake, bishops have almost free rein over funds and virtually no supervision. Moreover, some of the nation's largest dioceses are confronting worrisome structural problems--including rising labor costs and deteriorating school buildings and churches, as well as its more tightfisted parishioners. The red ink is already spilling. Boston's archdiocese is "facing a financial squeeze," says financial director Smith, and will run a deficit of about $5 million this year. The Archdiocese of New York has a budget gap of about $20 million. In Chicago, which publishes perhaps the most complete financial reports of any large U.S. archdiocese, the Church saw its operating deficit for parishes and schools soar 63% last year, to $23.3 million. But it's far from insolvent, with $790 million in assets, most of which is in real estate.

Damage to the rest of the Church's empire is also a concern. The U.S. Catholic Church is by far the largest operator of private schools, with 2.6 million students. An additional 670,000 students attend the 230 Catholic colleges and universities. The nation's Catholic hospitals account for 17% of all hospital admissions, while Catholic Charities USA--which collectively spends $2.3 billion annually--provides everything from soup kitchens to child care to refugee resettlement (table).

By no means would all of these institutions be vulnerable to billion-dollar legal settlements. Nor can the Church be likened to a unified corporation or a conglomerate. In the U.S., its members and assets are divided along geographical lines into 194 dioceses, each of which is legally separate (table).

This fragmentation cuts two ways. It is one of the Church's strongest defenses in the current legal firestorm, making it all but impossible for plaintiffs to go after the Church as a whole. The Vatican's bank accounts are also out of reach: As a sovereign state, it cannot be sued. Similarly, most of the Church's educational, medical, and charitable agencies are walled off. Although Boston College has a $1 billion endowment, for example, it is owned by a lay board of trustees, with no ties to the Archdiocese of Boston.

But the financial web that ties together the Church's massive network could be weakened if more big jury awards and settlements materialize. Churches, dioceses, and even the Vatican have an essentially symbiotic financial relationship--one that is largely hand-to-mouth and doesn't include large cash reserves. Joseph Harris, financial officer for the St. Vincent de Paul Society in Seattle and a student of Church finances, estimates that the nation's nearly 20,000 parishes had revenues of $7.5 billion in 2000. About $6.5 billion went to cover direct expenses, and much of the remaining $1 billion was used to subsidize Catholic schools.

These parishes also support the dioceses' operations, which in turn funnel money to other needy parishes, schools, or charitable programs. The dioceses also send money up the hierarchy. They contribute to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and also to the Holy See. "Rome doesn't usually offer to help distressed dioceses," says Bishop Joseph Galante of Dallas.

In fact, it's the reverse. The U.S. and German dioceses are the top two contributors to the Holy See, which in 2000 reported total revenues of $209 million. After years of deficits, the Holy See named then-Detroit Cardinal Edmund C. Szoka the effective budget director in 1990.

Within two years, Szoka had used management basics to reverse 23 years of deficits. He trimmed overhead, boosted investment return, tripled contributions from dioceses, and even began publishing a consolidated balance sheet. Still, because the Vatican depends so heavily on U.S. contributions, a few financially crippling jury awards at the parish level could send a ripple effect all the way to Rome.

Even with so much at stake, most bishops and Cardinals have little financial training and follow no Church-mandated accounting or auditing procedures, though some have professional advice as well as boards of advisers. "Every bishop is responsible for his own diocese--he doesn't have to send Rome a financial statement," says Szoka. This leads to wide variation. In New York, for instance, the late Cardinal John O'Connor, though beloved by his flock, had a reputation for being a terrible financial administrator. He was ill at ease with wealthy donors who could have pumped up Church coffers. Yet he loved to bail out money-losing schools and parishes, and blew through virtually the entire endowment.

Some believe Pope John Paul II chose Cardinal Edward Egan to succeed O'Connor in part because of Egan's strong record as a money mastermind. Egan mopped up a financial mess in the Archdiocese of Bridgeport and counts former General Electric Chairman Jack Welch as a trusted adviser. He's so adept at tackling costs with layoffs and school closings that he's known among some Archdiocese insiders as "Edward Scissorhands."

Yet even with the Papacy's growing awareness of the need for financial discipline, the system has no checks and balances, making it vulnerable to abuse. In 1998, the National Catholic Reporter revealed that Philadelphia's Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua had sunk $5 million into renovating his mansion, a seaside villa, and other properties in the early '90s, even as he closed money-losing parishes in impoverished North Philadelphia. Parishioners were so outraged that they took to the streets with signs depicting Bevilacqua as Darth Vader. In a more shocking case, the then-bishop of the diocese of Santa Rosa, Calif., resigned in 1999 after he allegedly forced a priest to have sex with him in exchange for covering up the priest's embezzlement of church funds. Only later did the laity learn the bishop had also incurred enormous losses through mismanagement, including offshore investments. And in Ft. Lauderdale, local law enforcement authorities are now investigating $800,000 in missing funds at a local Catholic parish. Getting the financial documents "has not been easy," says a spokesman for the Archdiocese of Miami.

So far, many of the doors that could reveal a true picture of the Church's finances remain tightly sealed. Kenneth Korotky, chief financial officer of the USCCB, says the U.S. Church has not even attempted to prepare a consolidated financial statement. Although Chicago, Detroit, Shreveport, and other dioceses do disclose their numbers, some of the largest--including New York and Philadelphia--refuse to release financial reports to their members. Charles E. Zech, an economics professor at Villanova University, in Villanova, Pa., says 38% of Catholics don't know how parish donations are being spent.

The same secrecy has obscured just how much the Church has paid out so far in settlements and how much more could be on the line. Mark Chopko, general counsel at the USCCB, says he "doesn't know the total volume of settlements" because many were sealed but estimates that $350 million has been paid to victims so far. But plaintiffs' lawyers insist the amount is close to $1 billion. Moreover, the legal climate is tilting against the Church, warns law dean Schiltz, who has defended both Protestant and Catholic churches against almost 500 sexual misconduct suits. Given the volume of damning media coverage, Schiltz predicts legislators in some states eventually will make it easier to sue the Church.

At the same time, the Church faces "an increasingly grim insurance situation," adds Schiltz. What little coverage it has is being exhausted. In Boston, "we have paid out just less than $30 million in claims and expenses relating to misconduct," says Smith, the Archdiocese's top financial official, and insurance has paid most of it. But he warns that insurance will fall short of all the claims now pending, which plaintiffs' attorneys predict could hit $100 million in Boston alone.

Inevitably, the Church will be forced to sell assets and cut programs to pay claims, as some hard-hit dioceses have already done. To settle 187 suits in the mid-'90s, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe had to sell vacant properties and a retreat center, says CFO Tony Salgado. Even so, it ran deficits for six years, which halted growth in ministries. Similarly, after sex-abuse settlements and a scandal involving its bishop, Santa Rosa was saddled with a $16 million debt. It was forced to ax 50 of 75 employees, sell land, and borrow from other dioceses. What's next? In Boston, there's speculation the Archdiocese might sell some prized land to Boston College, which wants to expand. And in Providence, lawyers are eyeing the diocese's most opulent property--the Aldrich mansion in Warwick, R.I., where John D. Rockefeller Jr. was married.

An additional strain on the entire Church is a mounting labor-cost crisis. For decades, the Church relied on an army of priests and nuns, paid next to nothing, to run its parishes and schools. Now experts fear the abuse scandal will deal a further blow to the priesthood, since even fewer men will choose this vocation--at least until the chastity rule is relaxed.

Meanwhile, with the average priest now 60 years old, "the number of active priests will shrink" as retirements pick up, says Brian Froehle, head of the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate. Add to that the decline in the ranks of nuns--whose numbers have dropped from 174,000 in 1965 to less than half that now--and the Church will have to rely more on lay workers, who are far more costly. The median salary for a diocesan priest is about $13,600, plus $16,000 in living expenses, says Sister Ellen Doyle, executive director of the National Association of Church Personnel Administrators. In contrast, parish administrators--often hired to do work once done by priests--are paid around $45,000, says Doyle. That's not to mention the need to increase the notoriously low salaries paid to teachers in most Catholic schools. But inner-city Catholic schools are in no position to hike salaries. As it is, "affording tuition [of $2,300] is a big problem" for parents sending their kids to McKinley Park Catholic School on Chicago's Southwest Side, says the Reverend James Hyland. Enrollment in Chicago as a whole dropped 3.4% in the current school year, the most in a decade, leading the Archdiocese to announce it would close 16 elementary schools.

Catholic charities could also be hurt. In Boston, Catholic Charities--the No. 2 provider of social services after the state--is already planning a 15% reduction in its central staff and is bailing out of some of its programs. Mostly that's because of reduced government funds, which provide 54% of its budget. But in the wake of the abuse scandal, fund-raising could also suffer. Health care won't be directly hit by the scandals, argues the Reverend Michael D. Place, CEO of the Catholic Health Assn., because much of its funding comes from government or private insurance. Even so, he concedes that "the current financial status of the ministry is challenged."

If anyone can see good coming out of so much bad, it's the Catholic faithful. Sister Jane Kelly, a 71-year-old nun who exposed sexual and financial abuse in Santa Rosa, figures the scandals can be an opportunity for reform. "Sexual misconduct of clerics has been an abscess on the Body of Christ for centuries," she says. And to its credit, the Church is moving toward more forceful measures to prevent further cases of sex abuse by priests--a subject the U.S. Bishops will address at their June meeting.

But there are few signs the Bishops--or the Pope, who has the ultimate say--are about to heed the will of reformers. "I don't see a major change coming in celibacy" right now, says Bishop Galante. Nor does the Church appear to be moving toward requirements for a more transparent system of financial reporting. "Our mission is to preach the Gospel," says Cardinal Szoka, who urges bishops to publish finances but dismisses American calls for financial reforms as a result of "secularization." The Church "is not an empire. It's not a financial entity. That's secular talk."

It's all a forceful reminder that, after 2,000 years of history, the Catholic Church isn't a democracy. But for the U.S. Church, the stakes have never been this high. Further delays and missteps may only increase the price it must pay--in money, in prestige, and ultimately, in power.

With Michelle Conlin in New York, Gail Edmondson in Vatican City, Ann

Therese Palmer in Chicago, Christopher Palmeri in Los Angeles, and Aixa

M. Pascual in Atlanta

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.