By Judy Valente

Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, WGBH, Episode no. 751

August 20, 2004

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week751/news.html

To view a video of this feature report, click here to go to the Religion & Ethics Web site, and click again on the "WATCH THIS STORY" link.

LUCKY SEVERSON, guest anchor: In Boston, a special mass this week to protest the planned closing of 81 Catholic churches. More than 1,000 Catholics gathered on the Boston Common, mostly priests and parishioners from churches that are scheduled to close in coming weeks. The Boston archdiocese announced the closures in May, saying it was because of declining mass attendance, a shortage of priests, and the rising cost of upkeep on old buildings. Parishioners say they'll continue to fight the decision.

|

And a second Roman Catholic diocese -- this one in Tucson, Arizona -- could soon declare bankruptcy. The diocese faces lawsuits demanding more than $20 million in damages from victims of priestly sex abuse. The Archdiocese of Portland, Oregon, filed for bankruptcy last month. Bankruptcy would allow a judge to determine what assets a diocese must relinquish to compensate victims. But it's a step that raises a number of questions, including issues related to the separation of church and state. Judy Valente reports.

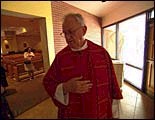

JUDY VALENTE: On this particular morning, Bishop Gerald Kicanas is doing what he calls his most important work -- being pastor to the people of Tucson. The occasion: the funeral of a popular 16-year-old who died of leukemia. Though sad, the occasion marked a rare chance for the bishop to escape his most pressing problem: how the keep the diocese functioning and still compensate victims who were sexually abused by priests.

To stave off a financial crisis, Kicanas is considering following in the footsteps of the Archdiocese of Portland by filing for bankruptcy protection.

|

Bishop GERALD KICANAS (Archdiocese of Tucson): There should be every effort made on the part of a diocese to try to compensate those who have been hurt, to seek their forgiveness. But sometimes the expectations of those who have been hurt are far beyond the assets or ability of the Church to respond to what they feel is needed in order to bring their healing about.

VALENTE: Two years ago, before Bishop Kicanas took over, this sprawling diocese serving 350,000 Catholics agreed to pay $14 million to 11 victims of sexual abuse. But now the diocese is facing 20 additional lawsuits seeking millions more in compensation. And that may not be the end of it.

LYNNE CADIGAN (Victims' Attorney): The ages of the victims that I represent -- the oldest is 45, and the youngest is only 10 years old.

VALENTE: Lynne Cadigan is an attorney who has 14 sex abuse cases pending against the diocese. She says she is seeking approximately $6 million for her clients, who include 3 sets of brothers from Hispanic farm worker families.

|

Ms. CADIGAN: To file for bankruptcy does two things. It re-victimizes the victims and makes them look like the predators; they're the ones chasing down the Church for money. It delays their lawsuit; it further prolongs their agony.

For these boys to come forward was very difficult. The parishioners ostracized them, called them "faggot," and they've had to switch schools. They had to testify in a criminal hearing. It's ruined their lives.

VALENTE: Cadigan's clients say the priest who abused them is this man: Father Juan Guillen, who is already in prison serving a 10-year sentence for sexual misconduct with a minor.

Other lawsuits against the diocese name this priest: Monsignor Robert Trupia. Although Trupia has not been convicted in a court of law, the Vatican recently forbade him to act as a priest after finding the sexual abuse allegations against him were credible.

Bishop KICANAS: Our litigation system is a first-come, first-serve system, and therefore the first people who come forward are compensated, and then there may be little or nothing left to help those who come later, who may be as hurt [as] or even more hurt than those who have come before.

|

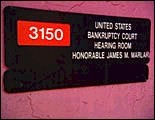

VALENTE: For the diocese, one of the main benefits of filing Chapter 11 is that all the pending cases would be consolidated in one court -- the bankruptcy court, where a judge would determine just how much money the diocese can reasonably afford to set aside for settlements with present and future plaintiffs.

THOMAS ZLAKET (Outside Counsel, Archdiocese of Tucson): Let an independent federal judge decide what assets there are, and then let that same judge divide those assets among the very many claimants. Tell me, what is unfair about that?

VALENTE: A diocese filing for bankruptcy is entering uncharted legal territory. A bankruptcy court judge could conceivably question a bishop's management decisions and order assets to be sold. A bankruptcy filing would also give victims' attorneys -- and the public -- unprecedented access to a diocese's financial records. Those records could help determine just how much the diocese's assets are worth. The argument is likely to center around property.

JOHN SHAHEEN (Property Manager, Archdiocese of Tucson): Look around you. There are no utilities, no phone poles. The water table itself could be 300 to 400 feet deep. We're in the middle of the desert, so it makes it very difficult.

|

VALENTE: The Tucson diocese says much of the land it directly controls, like this parcel, is scorched desert property with limited resale value. It estimates this and the other property it owns is worth about $3.2 million. But that figure does not include the diocese's 74 parishes, and herein lies the major battle to come in any bankruptcy proceeding: a potential showdown between canon law and civil law.

Bishop KICANAS: In canon law, it is very clear that I as a bishop have absolutely no right to demand the assets of the parishes. Those were given by people in trust to their own parish for its mission and for its work.

|

VALENTE: But county real estate records list the "Bishop of Tucson" as the owner of parish properties, including parish schools. That property has an assessed value of $48 million. Victims' attorneys maintain the market value of that property would be more than double that amount.

Vernon Schweigert is a Chapter 11 expert working with plaintiffs' attorneys

VERNON SCHWEIGERT (Bankruptcy Expert): The $48 million is probably an understated figure. I would estimate the value of those parishes probably closer to $160 million.

Ms. CADIGAN: The victims aren't asking enough money to close down any parishes.

VALENTE: The victims' lawyers are asking the diocese to borrow against the value of the parish properties to compensate victims.

|

Mr. SCHWEIGERT: There is a significant amount of equity in those parishes, and I believe the diocese could borrow certainly enough money against the equity in those parishes to pay any settlements contemplated. They could pay back that money over a period of time through the money generated by the diocese, and this would mitigate any effect on either schools or parishioners or anybody else, and at the same time take care of the legitimate obligations of the parishioners.

Bishop KICANAS: I am not able to put those properties up for collateral. Those are the properties of the parish, the people of that community.

VALENTE: But that is one of the looming uncertainties in a potential bankruptcy filing. A judge must weigh the arguments and could rule that parish land and assets, even money from the collection plate, could be used to pay for settlements, which has many pastors and parishioners just a bit worried.

Monsignor THOMAS CAHALANE (Pastor, Our Mother of Sorrows Parish, Diocese of Tucson): It's very difficult to put a value on the aesthetics of these beautiful pieces. ...

VALENTE (To Monsignor Cahalane): Any idea what the value of that window is?

|

Monsignor CAHALANE: I would consider it inestimable because of the fact that it was donated by my family and has very, very priceless sentimental value.

VALENTE: What if the parishes and everything in them become targets in a bankruptcy proceeding?

Monsignor CAHALANE: This space is very holy space, and it is unimaginable that the government would confiscate the space in a country where we have separation of church and state.

VALENTE: Father Raul Trevizo says if the diocese becomes financially strapped, it would devastate his parish of 5,000 mostly Hispanic families, because the diocese has to subsidize his parish school and programs.

|

Father RAUL TREVIZO (St. John's Catholic Church, Diocese of Tucson): This church building -- the parishioners built it, pretty much. They came and they laid the bricks. It's a legacy to a lot of people's commitment, in the past and in the present.

VALENTE: The diocese says it already has disposed of a number of properties in recent weeks, some to help pay for previous settlements.

For example, the diocese's downtown office building was transferred to a Catholic charitable entity in a noncash transaction. This former seminary was sold to a Catholic high school foundation. And this parcel was sold to another high school.

Victims' attorneys have argued in court papers that the diocese sold these properties to other church entities for far less than their market value, missing an opportunity to generate funds for the settlements. Diocese officials say they would have given these properties away to the high schools for free if they could have.

|

Mr. SHAHEEN: That's the mission of the Church. We're supposed to be expanding the educational opportunities for the children of the diocese. That's the Christian thing to do, but because of the original lawsuits, we had to sell the property.

VALENTE: For now, Bishop Kicanas is working hard to convince the people of his diocese that bankruptcy might be the best option.

Bishop KICANAS: I ask that you not look upon those who have been harmed as adversaries somehow hurting the Church.

|

Mr. ZLAKET: This is an issue that has never been decided in the history of this country. We're talking about a legal issue that is a first in 200 years of legal history, and it is certainly a first for the Catholic Church in America, so it ought to be given the utmost consideration.

VALENTE: This parish worker suggested that the bishop compose a special prayer for the diocese, seeking guidance through the financial crisis. It is now said at every mass.

Parish Worker (Praying): Merciful God, our hope in adversity, our comfort in sorrow, our strength in weakness. Guide us, your people. Give us new life and hope ...

Bishop KICANAS (Praying): Lead us through these times to become a stronger, wiser church ...

Monsignor CAHALANE (Praying): Help us to give greater encouragement to our brothers and sisters in their need. We ask this in the name of Jesus the Lord.

Bishop KICANAS: To make sure that the work of the Church is carried on -- that's the struggle: how to do that, knowing now that there are people within the very household of the Church who have been hurt and that we must try to help to heal. And yet, how do we also carry on the tremendous work of the Church?

(To woman parishioner): How are you doing, dear? Careful now ...

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: Glad to be here.

VALENTE: For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Judy Valente in Tucson.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.