Abuse of the Collar

Priests who have sex with vulnerable adults have done a `terrible thing,'

but Bishop Higi sees consenting adults – not victims

By Richard D. Walton and Linda Graham Caleca

Indianapolis Star

February 18, 1997

[See links to all

the articles in this series from the Indianapolis Star.]

The Rev. Robert Moran was the deep thinker whose guidance was sought by

other priests.

The Rev. Philip Mahalic was the smooth-talking "golden boy"

whose confident ways drew others to him.

Both priests of the Lafayette Diocese influenced impressionable younger

men to seek the priesthood. And both priests had abusive sexual relationships

with them, their former proteges charge.

|

| In the Pulpit: The Rev. Philip Mahalic is back preaching after therapy following an accusation of sexual misconduct with an adult. File photo. |

"Dear Bob," Moran's accuser bitterly wrote him in December

1994. "Fifteen years ago I came to see you for counseling because

Dad was dying and Mom was drinking.

"One night, you closed the door and turned out the lights, and my

life was forever changed."

Like Moran's accuser, the former seminarian who claims an affair with

Mahalic was once his parishioner. He says he relied on Mahalic for guidance,

money - and his chances of becoming a priest.

The accuser, a Lafayette man, says Mahalic fueled fears that critics

were out to drive him from the seminary, and portrayed himself as the

man's "protector." Declares the accuser: "It was always

made real damn clear that if I ever said anything, I'd be gone."

Moran refused to talk to The Indianapolis Star and The Indianapolis

News. Mahalic admitted some sexual wrongdoing but denied any affair

or abuse.

Both men are still in the pulpit, Moran at St. John the Evangelist Church

in Hartford City and Mahalic at Sorrowful Mother Church in Wheatfield.

In both cases, Bishop William L. Higi found inappropriate behavior by

his priests, but no abuse. This, despite the fact that Higi's own written

protocols for handling sexual misconduct cases cover acts by priests who

have a pastoral, therapeutic or counseling relationship with another adult.

The names of both accusers are withheld here because they consider themselves

victims of abuse. Also, Mahalic's alleged lover has since turned away

from homosexuality and married.

Moran's accuser went on to become a priest himself and to have a long-term

sexual relationship with Moran. Yet at the time he says Moran seduced

him, the accuser was 19 – in the bishop's eyes, no less at fault.

While Higi calls it a "terrible thing" when a priest abuses

his office, he points out that both accusers were by law consenting adults.

"Society is full of those kinds of situations," Higi says. "A

husband snarls at his wife – is she victimized by that? Some say

yes, some say no."

Celibacy, notes Higi, is a high calling – and a difficult one. He

compares priests who break their commitment to celibacy with average Catholics

who sin by having sex outside marriage.

"We have all kind of violations of commitments across the social

strata," he says.

Others, though, worry that such comments minimize the seriousness of cases

in which a priest misuses the power of his office to sexually exploit

a needy or vulnerable adult.

Such acts go beyond immorality, they say.

They are abuses of the collar.

Much like a doctor who seduces a patient, a priest who engages in sex

with a person under his care breaches the very trust that binds the relationship.

The Rev. Melvin Bennett of St. Bernard Church in Crawfordsville says priests

must be celibate and refrain from dominating others, whether they be a

seminarian, housekeeper or parishioner seeking help.

|

In this age, Bennett says, priests "can't be naive" about

using their power and influence for sexual advantage.

So powerful are priests that if they told the faithful they could skip

Mass on Sundays, some would do it "without batting an eye,"

he says.

"So if you told them something that was explicitly against God's

commandments, some would be inclined to believe that ...

"A priest represents Christ."

A special relationship

To his accuser, Father Moran represented solace.

Cancer gripped the 19-year-old's father in late 1979, when the young man

came to Moran for counseling.

In early 1980, soon after the death of his dad, the Purdue University

student again sought out the associate pastor at St. Thomas Aquinas Church

in West Lafayette.

That night – the night Moran "turned out the lights" –

the student cried. It would be just the start of his anguish.

A few years later, the student's mother died. His brother was diagnosed

with cancer.

Through all the hardship stood Moran, consoling.

Little is known about what transpired that long-ago night in Moran's church

office. Neither man would be interviewed.

But through knowledgeable sources and by reviewing correspondence, The

Star and The News pieced together a partial account of the

relationship and its aftermath.

Bob Moran was a beloved and learned priest whose sermons brought perspective

and life to the Bible. Moran had a gift for bringing a message home.

The priest is said to have persuaded his younger lover that their affair

was not wrong. Their relationship, Moran told him, was special –

so special that no one else would understand.

After he got involved with Moran, the student decided to become a priest.

With Moran's encouragement, he went to the seminary and was ordained in

the mid-1980s.

Not until late 1994 – after he confided his affair with Moran to

a clinical psychologist – did the younger man determine he was the

victim of a controlling man and denounce the relationship as exploitative.

"Our relationship as lovers is over," he wrote Moran.

Ironically, the young priest who brought the allegation earlier had been

named to the Diocesan Review Board, a panel Bishop Higi formed to advise

him on sexual misconduct charges against members of his clergy.

When he was appointed, no one could suspect that this board member himself

would claim to be an abuse victim.

If he expected the bishop to empathize, he would be disappointed.

"From my perspective," Higi wrote the accuser in the summer

of 1995, "you (and Moran) both mutually entered and maintained a

relationship of sexual misconduct for some fifteen years."

That the priest accuser also violated his celibacy is not disputed. But

to draw no distinction between the two men confounds and angers some familiar

with the case.

For at the start of their affair, it was the 35-year-old Moran –

not the Purdue undergraduate – who had pledged to live a chaste

life. And it was Moran's duty to lead his young parishioner away from

sin, not into it.

Higi did not mention those points in correspondence reviewed by the newspapers.

Rather, he wrote to the accuser that, setting moral issues aside, "the

evidence shows that you were free to leave the relationship at any time.

|

There was no coercion or binding force that held you in the relationship

unwillingly."

Higi also informed him that the investigation had "brought to light

questions" regarding his sexual behavior before meeting or knowing

Moran.

Noting that the accuser had hired a lawyer to press his complaint, Higi

issued a warning: Cease using the term "abuse" to describe the

relationship – or face possible legal action from the diocese.

Taking a stand

When Higi decided not to refer the allegation against Moran to the Diocesan

Review Board, a board member protested. In a letter to the bishop, the

Rev. Richard Weisenberger reminded Higi that the written protocols cover

abuses that occur during counseling.

"From what we know this allegation ought to have been referred to

the DRB and it bothers us that this did not happen," Weisenberger

wrote in June 1995.

The priest cited a second concern: Father Moran remained in active ministry.

"We have grave reservations about his posing a threat to others who

come to him for counseling or have other contact with him."

Higi responded that protocols had been followed. He said the review board

is convened if there is concern for the safety of children. In the Moran

case, he noted, "children are not involved and never have been."

"Bob Moran was confronted, immediately, per the Protocols. He was

put into a therapeutic situation, per the Protocols," Higi wrote.

Board members, remarked Higi, were getting a narrow view of the case from

the accuser, who left the review panel after making his allegation.

Weisenberger, though, still was not satisfied with the bishop's decision.

He consulted the other board members. All promptly resigned.

The accuser, too, had tried to persuade Higi to take stronger action against

Moran.

"Sexual abuse," he wrote the bishop, "is not limited to

what is done to little children."

Higi's written reply: Whatever takes place regarding Robert Moran "ought

not to be your concern."

To the alleged victim, Higi seemed overly protective of the abuser.

That came through in documents giving the accuser's account of a March

1995 meeting with the bishop. The papers allege Higi asked the accuser

not to tell anyone about the relationship with Moran. When the accuser

protested that keeping quiet about the reasons he suddenly was leaving

his job in the diocese would hurt his "good name," Higi reportedly

responded by asking the accuser to "take that hit."

|

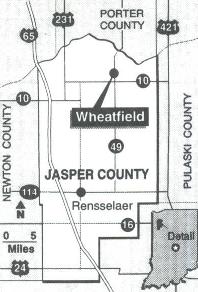

| Back in Pulpit: The Rev. Philip Mahalic was assigned to Sorrowful Mother Church in remote Wheatfield after receiving therapy for sexual misconduct with an adult. Staff Photo / Susan Plageman |

Because Higi cut off interviews with the newspapers, his version of

that meeting could not be obtained.

But the accuser believes Higi was trying to silence him so the bishop

could keep Moran in the pulpit.

Eventually, Higi did remove Moran from his ministry. He sent him away

to therapy.

About 10 months later, Moran returned to his Hartford City church. He

was greeted with yellow ribbons strung in the trees by supporters who

had missed him.

At one weekend's Masses last May, Moran acknowledged that a long-term

friendship or relationship with a fellow priest had soured and broken

off badly. Moran spoke of his rededication to living a virtuous life.

After each brief statement, parishioners, some in tears, applauded.

"All of us who love Father Bob, and that's 99.9 percent of us, felt

so glad to have him back," said parishioner Marge Piguet.

Moran remains respected in the chancery, too.

Higi's second-in-command, Vicar General Rev. Robert Sell, described Moran

as a theological "guidepost" for other priests in the diocese.

"He has always been judged as an exemplar of what it means to be

a dedicated priest, in terms of ... care and shepherding of other people,"

Sell said.

In contrast to such support for Moran, his alleged victim felt shunted

aside.

Believing he had been treated unjustly by the diocese he had served for

10 years, he turned suicidal.

"I felt there was no hope for any happiness ever in my life,"

he wrote to Higi. "I'm not sure why I didn't go through with my plan

– except that something inside of me said, 'These people aren't

worth it.'

"I've lost a lot so far because I trusted Bob Moran, and trusted

you."

Last June, the accuser let Higi know that his life as a priest was over.

"I am no longer Roman Catholic," the note said.

A year and a half earlier, in his bitter letter to Moran, the accuser

had painfully acknowledged that he became a priest because of his sexual

involvement with Moran.

"I must now face the fact that my life, at least in terms of ordination

and vows, has been a farce," he said.

"It just happened"

Phil Mahalic's accuser was no innocent.

In fact, it was he who first came on to the priest.

"I told him in confession that I was very much attracted to him."

Father Mahalic, then a pastor of St. Mary Church in Muncie, made it clear

to his parishioner that nothing could come of that, the man says.

But he adds that the priest became more engaging afterward.

A friendship blossomed.

To his insecure friend, Mahalic seemed to be everything his admirer was

not – popular, goodlooking, successful.

Mahalic, who recently turned 50, had played football at Rutgers University.

He drove flashy cars. Before he entered the priesthood, he owned a car

dealership in Peru, Ind.

The two men went to movies together. They took a cruise to the Bahamas.

With Mahalic's encouragement, the accuser applied to the seminary.

Once accepted, though, he says Mahalic took the credit.

Mahalic told him he had recommended him after another priest would not.

It would become an abusive pattern, the accuser says: Mahalic putting

him down – and building a dependence.

The 42-year-old accuser says he is an alcoholic who had stopped drinking

years before he entered the seminary. Yet he says Mahalic told him it

was all right for him to drink as long as the priest was with him.

Mahalic denies that. "I said, 'If you want to drink around me, I

don't care.' . . . The liquor was in the closet and he just helped himself."

|

Responds the accuser: "He has a nice way of twisting."

The priest, he says, "got me started again."

The accuser contends he and Mahalic were drinking heavily before their

first sexual encounter.

It was the late 1980s. The accuser was attending the seminary; Father

Mahalic had left St. Mary's and was working as a Catholic chaplain at

Wabash College in Crawfordsville. The accuser says they were watching

a movie in Mahalic's Crawfordsville home when the priest suggested they

continue viewing it in his bedroom.

Then, "it just happened."

Though years had passed since he confessed his attraction, the man recalls

he still was smitten with the blond-haired Mahalic.

"He was the golden boy of the diocese."

Ordained just a few years earlier in 1983, Mahalic already held the influential

post of director of vocations.

That job – the liaison between seminaries and the bishop –

was just one reason the seminarian says he felt beholden to the priest.

Virtually from the time he entered the seminary, the accuser says, Mahalic

had suggested that he alone stood between his friend and failure. Mahalic

told him how he had to do some fast talking to fend off one critic or

another, the accuser says.

He adds: "I really felt like if I pissed him off, I would be gone."

Mahalic, interviewed in his rectory at Wheatfield, insists he never had

or claimed influence over the man's ultimately failed seminary bid.

Mahalic says he is not gay, and maintains that alleged first night of

sex at Crawfordsville never happened.

He brands his accuser confused and unbalanced.

Yet Mahalic admits to sexual contact with the accuser. He says it occurred

after he no longer was vocations director, in the early 1990s.

By then the pastor of the fledgling Holy Spirit Catholic Church at Geist,

Mahalic says his friend would visit his home and sometimes stay overnight.

Mahalic contends that on three occasions – each separated by a year

or more – he awoke in the morning to find the man at his bed.

Two of those times, Mahalic says, he permitted the man to masturbate him.

"I should have stopped it immediately and I didn't," Mahalic

says. "I allowed him to touch me sexually, without reciprocating."

Each time, Mahalic says, he was taken by surprise. Each time, he says,

he assumed it would not happen again.

Still, Mahalic admits he never reproached his accuser during or after

any of the advances.

After the first time, the priest says, he just looked disgusted. After

the second, he went into the bathroom. After the third, he says, he began

locking his bedroom door.

Mahalic contends he was taken advantage of by his house guest. "If

something like that would happen today, I would certainly stop it immediately."

Mahalic's version of events draws laughter from his accuser. "He's

such a weak guy," the man says.

The accuser scoffs at the suggestion that Mahalic was a victim of unwanted

advances or that the contact was limited to two encounters. Nor, adds

the accuser, were the acts confined to masturbation. He says they included

intercourse and oral sex.

A murky ending

Nothing might ever have been revealed, however, had the accuser not become

distraught one night in early 1993. His affair with Mahalic over and realizing

his own problems had doomed his bid to become a priest, he went out and

"got really bombed."

He was jailed. He tried to commit suicide.

The next day, he revealed his relationship with Mahalic to a hospital

counselor. The counselor's advice: Tell the bishop.

The accuser says he related his sexual relationship to Higi. After hearing

that allegation, as well as another more serious charge later found to

be false, Higi sent Mahalic to therapy.

The bishop says he acted immediately.

"Mahalic was out of his (Geist) parish almost overnight," Higi

said.

Mahalic, however, says he was not removed. He says he resigned in the

spring of 1993 "for the good of the parish."

There are other contradictions.

For example, Mahalic says he never gave his accuser spiritual advice.

The accuser says that, back at St. Mary's, he regularly made his confession

to the priest.

Mahalic says he never saw his accuser drunk. Yet the priest describes

one night at Geist where he says the accuser was "smashed."

Mahalic said he lives a celibate life. Later, in the same interview, he

said his acknowledged sexual contact with the accuser violated celibacy.

And Mahalic denies being supervised since returning from therapy.

Yet at his first assignment back – at St. Lawrence Church in Lafayette

– Mahalic was supervised, says Vicar General Sell.

From the start of their relationship, recalls the accuser, Mahalic was

reassuring about the accuser's homosexuality. The man says the priest

told him to quit worrying about it "and accept who I am."

Mahalic says he recalls no such conversations. He says he had "no

inkling" his friend was sexually interested in him.

"It wasn't something I was expecting, and therefore he could have

been doing all kinds of things that just went right over my head,"

Mahalic says.

Bishop Higi expresses confidence that Mahalic has learned his lesson.

"It's something he wasn't supposed to do and he needed to understand

it was wrong," Higi says.

"He received the tools, so to speak, to make sure it never happened

again."

Mahalic's accuser wonders.

The way he sees it, nothing's been solved. He continues to worry that

Mahalic could victimize others.

"Because the bishop's got him in that little parish out in the middle

of nowhere."

Mahalic's current post in Wheatfield is at the northern tip of the diocese,

in rural Jasper County. It was decided, the diocese says, that Mahalic

no longer warranted closer scrutiny.

For his part, Mahalic says he has set aside his bad feelings toward his

accuser. The anger, the priest says, has turned to compassion. "I've

forgiven him a long time ago," Mahalic says.

"I'm stuck – I have to. It's part of what I'm all about."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.