The Priest and the

Boy

Father Jim brought a little bit of hell to the kids of

St. Joe's. Then one of them grew up and got mad

By Jason Berry

Rolling Stone

June 20, 2002

|

|

| [Click images to zoom.] |

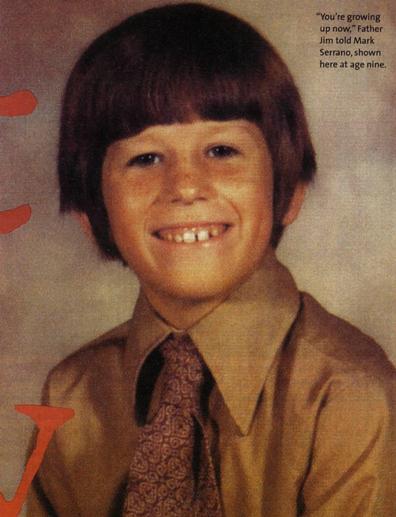

THE GROOMING PROCESS BEGAN TENDERLY. Mark Serrano was nine years old in 1974, a fourth-grader at St. Joseph's elementary school in Mendham, New Jersey, when the nun scolded him for misbehaving and ordered him to see the pastor. Mark was afraid. He'd never been disciplined by anyone besides his parents. But he'd served as an altar boy for Father James Hanley, so he was familiar with the man. Father Jim waited in the teachers' lunchroom, sitting with his back to the window. "You can do better than this—I know you can," the priest told him. "Don't give the teachers a hard time."

Mark's fear melted. In Father Jim he saw kindness.

A few days later, Hanley approached Mark and said, "Come on by the rectory to see me. Anytime you want."

Mark was intimidated the first time, as if entering the sacristy in church, a holy place. An imposing housekeeper ran things downstairs. Up in Father Jim's suite, though, Mark found a whole crew of boys about his age, eating pizza and horsing around, with the priest like a big buddy at the center of it. At home, Mark was part of a large, close family, two parents and six siblings. But the rectory promised to be a fun place, too—like a clubhouse.

To visit Father Jim, you first had to ask the housekeeper. She'd order you: "Go yell up."

"Father Jim?" you'd call up the stairs.

When Hanley's voice boomed down, "Yeah?" you could head up. If no response came, you knew to return another time.

Mark started out visiting after school or on Saturdays, maybe once or twice a week. He had just turned ten when one day Hanley invited him into his bedroom. They were alone.

"You're such a good kid," Hanley said, smiling. "I wish you were my kid."

Mark had never felt so flattered.

"Your parents love you so much, Mark."

Mark never doubted his parents' love. His mom and dad encouraged all of the children and were generous with hugs and kisses. But they were reticent about putting every emotion into words. "I love you" was one phrase Mark hadn't heard them say.

"Your father tells me you kiss him every night before you go to bed," Hanley went on. "He calls you 'the lover.'"

Mark had no idea his dad called him that.

"You kiss your father good night," said Hanley. "Now give me a kiss goodbye." As he spoke, he put his lips to Mark's.

"He talked so much about kissing," says Serrano today. "His kissing me was meant to be like kissing my father. He was so subtle and patient."

They met that way, just twenty to thirty minutes at a time, once or twice a week, throughout that year—never a sexual touch, only the slow, emotional seduction, sealed with a kiss.

One afternoon, as Father Jim sat in his recliner, he told Mark, "Hop up."

The dutiful boy sat on the priest's lap. Like a dad about to read a story, Hanley unfolded a copy of Hustler and turned the pages, showing Mark photographs of nude women, "telling me all about the clitoris, how it fills up with blood just like when boys get an erection and blood rushes into the penis," Serrano says.

Wearing his school uniform of blue trousers, white shirt and clip-on tie, Mark sat there, "somber and quiet," he recalls, staring at the pictures. "My adrenaline was rushing, and I felt as if my hair stood on end." He felt awkward and uncertain about how to react.

|

"You're growing up now," Hanley said. "You're going to have feelings, and think about girls. You're going to play with yourself. The hair is growing around your penis and under your arms—someday you'll have hair on your chest. This is good and natural, Mark. By the time you're nineteen, all you'll think about is girls and sex!"

"Really?" asked Mark.

"Oh, yeah," said Hanley, telling Mark that as a teenager he had masturbated regularly while thinking about girls.

Not long afterward, during another session in the rectory, Hanley asked the boy, "Do you know what French kissing is?"

Mark shrugged.

"Would you like me to show you how?" asked Hanley.

SINCE 1985, SOME 1,500 CATHOLIC priests in the U.S. have been named in legal actions for sexually abusing youngsters and teenage boys. More than 1,000 victims have filed civil suits in the last two decades. The church has hemorrhaged more than $1 billion, by various accounts. Still, only about eighty priests have gone to prison. The bishops' fortress mentality of refusing to report names to prosecutors has helped hundreds of predatory priests evade punishment. Hush money has been central to the strategy, with negotiated legal settlements, often for hundreds of thousands of dollars, in exchange for a victim's silence. No one knows how many kids have been sexually abused by priests, though everyone who has studied the problem agrees that the numbers are large. In 1993, the Rev. Andrew Greeley, the leading sociologist of the American Catholic Church—and an unflinching critic of its hierarchy—published an estimate that in the previous generation, 100,000 youngsters had been molested by priests. [Note from BishopAccountability.org: See Greeley's article.]

|

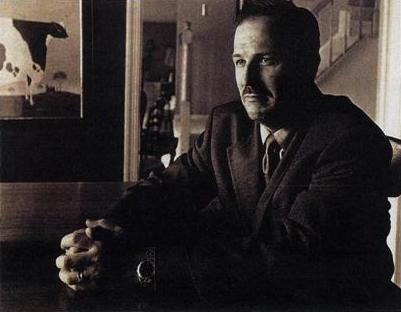

One of those children, Mark Serrano, is thirty-eight now, with reddish-brown hair, a handsome face and an athletic build. He lives in Leesburg, Virginia, with an attractive wife, three children and a fourth on the way. His company consults with businesses on federal-government policy issues.

Mendham, New Jersey, where Mark Serrano grew up, has hilly streets with yellow maples and dogwood trees that shimmer white in springtime. The Serranos bought a two-story house there in 1965, the year after Mark was born. His father, Lou, a former New York City police officer, left the force after a serious injury and found a job as a tool-and-equipment salesman, becoming the top representative in his division.

The family went to Mass each Sunday at St. Joseph's, a small Gothic-revival church built in 1860. Their children, five boys and two girls, all went to St. Joe's school. Mark was the fifth in line. He was seven years old in 1972, when a new pastor moved into the rectory.

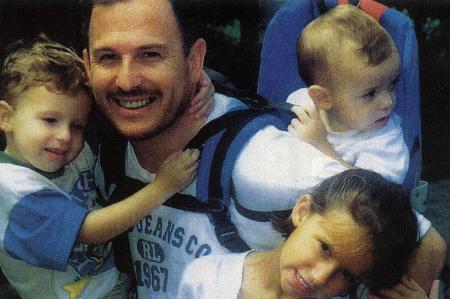

| The Victim Fought Back |

|

| Serrano today, a family man living near Washington, D.C. He organized a historic meeting in April, when he and eight other victims of Hanley convened to confront a church leader. |

The Rev. James T. Hanley grew up in Totowa, New Jersey, just twenty-five miles away, and graduated from Seton Hall University with a degree in classical languages. He entered Immaculate Conception Seminary in Darlington, New Jersey, and was ordained in 1962. St. Joe's was his first parish as full pastor. He was thirty-six then, with a booming laugh and Irish gusto. He ran the church youth program, taking kids on fishing trips and to the amusement park at Seaside Heights. He befriended many of the parents, too.

"He was a charming guy," says Lou Serrano, "a great after-dinner speaker. We had an involved parish. He was like the head of a family." Five feet ten and plump, Hanley enjoyed his beer and vodka. His sermons showed flashes of wit, and he seemed so natural, playing piano and singing for Knights of Columbus dances and parties at private homes.

Lou and Pat Serrano welcomed Jim Hanley into their house, for dinners with the family and summer days in the backyard pool. He even said Mass in the home. Those visits to the Serrano household only magnified his presence in Mark's eyes.

MARK HATED THE SENSATION as the priest's fleshy tongue entered his mouth. Yet he felt frozen: His mind could not send the signal "Walk away."

The kisses became a regular part of their meetings, and soon Hanley was rubbing Mark's crotch through his pants, too. Now the visits filled the boy with anxiety, but he was unable to express his confusion about the mingling of fear and erotic sensation. He kept returning, yet he hated the fact that he did so.

Afterward, he'd race home to join the family in time for dinner. With nine people sitting around the table, benches on either side, Lou and Pat at opposite ends, the kids vied with one another to talk about what they had done that day. Mark talked about friends, school, sports—anything but what happened with Father Jim, who heard the confession of each family member, who gave them the body and blood of Christ at Mass. At Hanley's invitation, Pat and Lou had become Eucharistic ministers, giving out Communion at Mass.

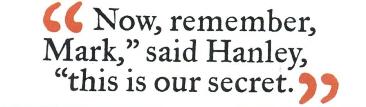

"Now remember, Mark, the priest would tell the boy after each encounter. "This is our secret. This is something special that you and I share. Best not to share it with Mom and Dad."

Mark obeyed without thinking. Hanley was the most holy and exalted figure in the boy's life, the father who had authority even over his biological father. His spiritual authority made him too overwhelming to even question, let alone challenge.

But Mark's mother noticed that he had begun talking in his sleep, sitting up in bed, babbling words no one could understand. Even when he was awake he was afraid, but couldn't say why. He occasionally got into fights at school, his behavior so aggressive that a nun finally slapped him in the face and sent him to the principal's office. Another time, he was eating in the lunchroom next to a girl and her mother, who was visiting. The sense of intimacy between that mother and child hit him like a punch. The secrets he had bottled up inside abruptly started him sobbing. He pictured himself caged, locked in silence, his parents slipping away as Father Jim took their place.

|

In sixth grade, Mark quit the Boy Scout troop, which met at the church. He had a new crowd—"a level of privilege being in Hanley's boys' club," he reflects. The rectory had become an erotic playland for adolescent boys, a place where Hanley screened hard-core pornography on the VCR. To gain membership, you agreed to one unwritten law: Nobody talks about the club.

BILL CRANE, 36, IS TWO YEARS younger than Mark and came from another large St. Joe's family—six kids. Today he owns a horticulture business in Clackamas, Oregon. One day, as "a tiny, scrawny kid" of eleven, he recalls, "I was changing into my altar-boy gown, and Hanley squeezed my arm. 'You lift weights? You're really strong,' he said. That made me feel so good—I had never worked out."

He too became a member of the rectory boys' club. He recalls Hanley telling them, "I know you guys think the Virgin Mary was a virgin. I'm here to tell you she wasn't. Joseph and Mary went through a lot of sexual activity, and I'm going to show you what kind."

Hanley had several groupings of boys, spaced two to three years apart, Crane says. On a Monday he'd have one bunch, Tuesday another, Wednesday a third; younger participants occasionally overlapped with older kids, but by fourteen most of the guys began to curtail their sexual contact with the priest. Many continued to visit, though, to watch porn, drink beer and tell the priest about their sexual exploits with girls, stories he enjoyed with vicarious relish.

The priest's advances on Crane "began as close hugging," he says. "He told me how much he loved me and put himself all over me, where you didn't have a chance to get away. He started tickling me, and it slowly turned into more."

As the club membership grew, emotions could flare. When another youngster—a year behind Crane in school—arrived on the scene, older boys got jealous, thinking, "What is this new kid doing hanging out here? He's taking our time from Hanley."

When he quit the Boy Scouts, Mark Serrano began a new activity: the track team. He was wiry enough to be a sprinter but opted for the more punishing long-distance races. "Running was my way of fleeing, trying to escape Hanley's abuse when I couldn't tell my father," he says.

One day, when Mark was eleven, Hanley had a new demand: that the boy pull down his trousers and underpants before sitting on the priest's lap. Father Jim then produced a new toy: a vibrator with a heating element, which he said he needed for his wrist after he broke it.

Hanley put the vibrator on the boy's exposed penis. The sudden heat and vibrations sent a surge of feeling through Mark as he felt himself losing control of his body. His legs stiffened at the shock of erotic release, something he had never experienced. "What I really felt was terror," says Serrano. "At that time I didn't even know about masturbation or intercourse."

At the moment of ejaculation, Father Jim brought out a handkerchief; he did so every time, like a ritual, cleaning the boy before he set him free. Mark dressed in embarrassed silence, then headed out the door with a miserable sensation of wetness. Each time he left the rectory that way, as if on a red-alert panic, Mark would jump on his bike and tear through the hilly streets, wind rushing hard in his ears, as if the air could wash away the feelings.

Mark felt ashamed when his friends began discussing masturbation. He was embarrassed that he had "already learned about my body, but not on my own. I did not like feeling weird and different ... and I did not know why I did. I felt great pain when my friends were learning about their bodies." He told himself, "I am not like them"—a seasoned veteran of the discoveries they were making on their own. Mark felt weird in seventh grade when a friend was amused to learn he had never kissed a girl. Mark had been kissed by Father Jim for years by then, but was too embarrassed to try it outside the rectory. He would masturbate but slap himself in the face afterward. This happened on dozens of occasions, he says. Sex with yourself is good, Father Jim had said. Therefore, slapping himself was Mark's way of saying that what Hanley told him was bad.

Hanley took Mark out to dinner and movies, usually with other boys; he also plied him with gifts—a gold cross on a chain; birthday cards with cash. Parents thought that on the afternoons and weekend day trips, their sons were in the safest environment imaginable: with their priest and friend.

While holding the vibrator on Mark's penis one day, Hanley said, "I want to put my mouth on you."

Mark remembers his chest heaving; the screaming in his head during the strange alchemy of revulsion and sexual rush, his legs unable to move.

"Now there's some of you inside of me," said Father Jim when it was finished.

Hanley seemed almost gleeful about the new stage of sexual contact. He performed oral sex on the boy dozens of times from age twelve to fourteen. Each time the adrenaline rush of sexual intensity was overwhelming. "I felt my hair standing on end, and a terrible voice inside: 'This isn't right,' " Serrano says today.

But why couldn't he bring himself to leave, to halt what he so despised? "It was like being brainwashed," he says. "I had no developed sense of self-protection. He stripped me of that instinct."

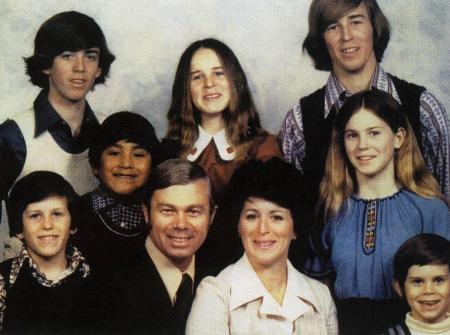

| Family Album |

|

| The Serrano family in the early 1970s: Mark, bottom left, would race home from the rectory to be with his parents, Lou and Pat, and his six siblings. |

|

| The Serrano family today: Mark with his daughter and two sons. His wife, Stacy, is expecting a fourth. |

Only once did Mark manage to break away. He was thirteen by then, a summer afternoon when, after performing oral sex on Mark, Hanley asked, "Will you do it to me?"

The priest then stood and unzipped his trousers, extending his penis toward the boy, who sat on the arm of the recliner. Suddenly, Mark jumped up and bounded into the bathroom, shutting the door behind him. He stood at the sink, staring in the mirror, looking at his bugged-out eyes, his mind shouting, "How do I get out of this?"

When he stepped back into the room, Father Jim was fully dressed, sitting at his desk, undoubtedly realizing that he had crossed the line. He never asked again.

For the most part, Hanley made sure the boys were not together when he had sex with them. As the encounters intensified, however, Hanley invited Mark, then twelve, and another boy to stay overnight at the rectory. After dinner he said, "OK, boys. Strip and hop into the shower!"

He marched them naked, dripping wet, through his suite. After the shower he said, "Hop into bed, boys." Hanley lowered the lights, took off his clothes, wedged his body between theirs and performed oral sex on Serrano, who looked at the other kid, each of them humiliated. Hanley fell asleep between them.

Later that week, Hanley played piano at a church function for parents and told a joke that made Lou and Pat Serrano uneasy. Once home, Lou said to Mark, "Father Jim told us a story about you and another boy in the rectory. He said he scrubbed you down with Bon Ami cleanser. That made your mom wonder: Is it true?"

"No," he said. The soap was not Bon Ami. But his heart sunk at a rare chance to break the silence. Instead he felt like he had a lock on his jaw.

Hanley snared at least fifteen boys in his decade at St. Joseph's. The most amazing thing about those crimes is that adults were often close by when he committed them. There was always an assistant pastor living down the hall. The housekeeper saw boys coming and going, and washed the sheets, towels and handkerchiefs Hanley used to clean the boys after sessions. Even Hanley's mother stayed at the rectory from time to time.

Did the adults sense something wrong but not want to know more, or did they simply deny the implications of such evidence?

Child abuse was not an issue on the media's radar screen in the 1970s. Parents trusted Hanley enough to let their sons sleep over at the rectory.

They went on trusting Hanley until he showed clear signs of falling apart. By the late Seventies, his drinking had gotten out of hand. Lou Serrano saw him teeter on the altar and urged him into detox. But once he returned to Mendham, he was soon drinking again and back to his old ways.

Mark visited the rectory regularly through eighth grade. He would use the vibrator on Hanley at Hanley's request, holding the device as it stimulated the priest to climax. One afternoon, however, Father Jim muttered, "I can't do it"—he was unable to ejaculate. "I've done it twice today," he said, intimating that other boys had already been to visit.

At fourteen, Mark began making new friends in a school across town, so visiting the rectory required effort; though the clubhouse was always there with porn videos and magazines, Mark was getting interested in girls and less interested in Father Jim.

He was respectful of girls, but each relationship turned into an emotional box, so consuming that he barely saw his buddies. Girlfriends became best friends, obsessions, proof to himself that he wasn't gay. At seventeen he lost his virginity to a girl he was dating. However, he says wryly, "I had been deflowered as a child."

LOVE" WAS A WORD FATHER Jim used often as a means of seducing boys into his little club. "He fell in love with me, absolutely," says Bill Crane, who today is married and has had no other sexual relations with men.

As a high school freshman working part time as a groundskeeper at St. Joe's, Billy became interested in a girl. Hanley became jealous. "Fornication is a sin!" he fumed without a hint of irony over the pornography he had shown to Billy and others.

"Nothing is going on," the fourteen-year-old said.

"That's bad enough, but you have to lie to me!" Hanley barked. "You shithead!"

Hanley's drinking got worse, and his moods turned dark without warning. One night Billy visited him in his room. Father Jim was in boxer shorts, tanked on vodka and crying.

"Billy, I love you," he said. "I need to talk to the bishop. I need to move on."

"You can't leave!" the boy protested, crying himself.

In 1982, Hanley announced his departure from St. Joe's; many people knew he needed to detox again. Still, the parishioners held a huge going-away party to show their affection. By autumn, he was on a sabbatical at a Franciscan mission in Santa Barbara, California.

Mark Serrano was a freshman at Villanova University by then. The impact of the abuse was stuffed away in a part of himself he tried to avoid. He became "a slave to studies ... I had the most boring freshman year imaginable." A childhood friend from Mendham had gone to Villanova, too. On November 13th, 1982, they got a letter, postmarked Santa Barbara:

"I'm glad things are going well for you and that the girls are beating down (almost said meat) your door!" Hanley wrote.

"I'm cruisin' outa here next week with mixed emotions—it's been idyllic but unreal—I'm a bit homesick and actually miss work and yearn to feel needed again. . . ." He continued with the small talk, then wrote, "About 14,000 attend Santa Barbara here—all walk around half-naked, riding bicycles, getting stoned on beaches in front of bands, fornicating in the middle of the streets—you'd love it. But, of course, there's lots of money here!

"Anyway, you guys—behave, sort of. Watch out for casual, cheap sex, or else it gets expensive....

"God bless and take good care—

"Love, Jim"

Within a year, Mark had transferred to Notre Dame and severed contact with Hanley. In 1984, his junior year, he read a newspaper article about a Louisiana priest who had been indicted for sexually abusing boys. "That's a crime?" Serrano thought. Then, "What he did to me was illegal! At least it didn't affect me," he thought. "But what if he's doing it to other kids?"

In February 1985, Serrano decided to tell a girlfriend what Hanley had done. She took him to meet with a nun, who advised reporting Hanley to the bishop back home. His girlfriend suggested he get therapy. At twenty-one, Serrano began to rethink his childhood.

With the help of a sympathetic clergyman, Monsignor Kenneth Lasch, St. Joe's new pastor, Serrano got an appointment with Hanley's superior, Bishop Frank Rodimer, on June 5th, 1985, at the diocesan center in Clifton, New Jersey. The bishop, Serrano says, told him that Hanley claimed his problem was alcohol, for which he was being treated. "I have to give him another chance and take him at his word," said the bishop, according to Serrano. (Rodimer declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Over Thanksgiving 1985, Mark sat in his parents' bedroom, visiting his father, who was recovering from surgery. "I want you to know Father Jim fondled me and abused me," Mark told him.

A few days later, Lou drove to Hanley's new parish in Wayne, New Jersey, and asked him what he had done. "Mark is like a son to me," Hanley said. "I love you people." The sexual activity, he said, "wasn't as serious as you might think."

Mark was unable to tell his mother. At home on New Year's Eve, her husband told her instead. Pat wept. Jim Hanley had said Mass in her home!

|

In early January 1986, Pat Serrano saw Hanley's picture in a Catholic newspaper, saying children's Mass at a church in Wayne. The Serranos and their son met with an attorney, who began negotiations with the Paterson diocese for civil damages. The result was a $350,000 settlement, of which legal fees took about a third, says Mark. The agreement stipulated that the Serranos could not make public statements about the terms, unless the church provided a formal release.

|

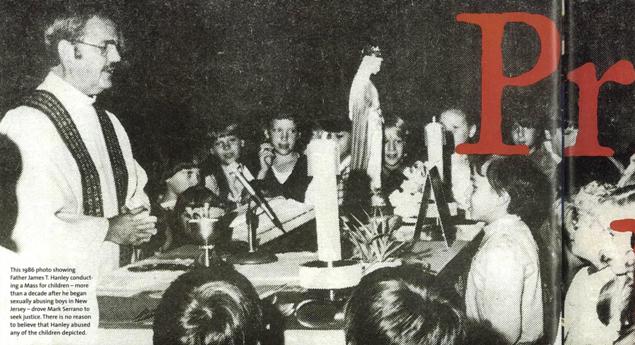

| This 1986 photo showing Father James T. Hanley conducting a Mass for children—more than a decade after he began sexually abusing boys in New Jersey—drove Mark Serrano to seek justice. There is no reason to believe that Hanley abused any of the children depicted. |

Serrano used much of the settlement to pay college expenses for his siblings. Still, he was haunted with flashbacks of Father Jim. "We'd be on the phone with him two, three hours at a time," recalls his mother. "He was sobbing, the thoughts were so terrible to him. Finding the words was a terrible hurdle." Going to Mass became a nightmare for Serrano: When he saw a priest on the altar, he imagined Father Jim's genitals.

He graduated from college and began his career, working in Republican political campaigns. Therapy helped him see that despite the obsessive relationships with women, he was sealing himself off emotionally. By the time he met Stacy, his future wife, he had left the Roman Catholic Church, something his parents understood but could not bring themselves to do.

In 1993, with the national media reporting on pedophile-priest cover-ups by bishops, three former St. Joe's altar boys came forward in the press and also met with police. The climate emboldened Mark to meet with Morris County prosecutors, despite his non-disclosure agreement with the diocese.

On April 12th, 1994, a detective knocked at Jim Hanley's apartment door in Lincoln Park, New Jersey. Hanley, although still a priest, had no parish and was working as a bookkeeper. Waiving his right to counsel, he spoke freely.

By the time Hanley spoke to authorities, the statute of limitations on his crimes against Serrano had run out. (Since 1996, there has been no statute of limitations for instances of serious sexual assault in New Jersey.)

"I fully accept the blame," he told police. "I want Mark to know that he is not to blame for any of it. It's all my doing and part of my disease, my alcoholism, uh, my own sexual history, that has brought this hurt upon him."

Hanley said his first victim was a boy at St. Christopher's parish, in Parsippany, New Jersey, where he served before he arrived in Mendham. "I was very friendly with the family," he said. "I would often go over and visit [the victim's] mother and father. They were very much involved in the church."

Many pedophiles were themselves abused as children. Hanley claimed he was not. He blamed a seminary system that expected priests "to be alone, to be a manly man.... Guys sit in their room and drink. The bottle gives you comfort.. You couldn't have close male friendships, so you start to bond with teenagers....

"Eight years, putting the pieces back together again, and it's going to be a lifetime.... If I could go back—but you can't. It's a toughie. It really is. And these are all, all good kids. Every one of them. And they have to know that."

For Serrano, this was not enough. On the night of October 6th, 1994, Mark and his parents rang Hanley's bell, hoping a surprise visit might inadvertently reveal information that would make his prosecution possible. Mark had rehearsed his statement. Lou was rigged with a body mike.

Hanley was living in an apartment complex in Lincoln Park, a twenty-five-minute drive from Mendham.

"Hi, Lou," said Hanley as the elder Serrano put his foot in the doorway.

"We need your help, Jim. Can we come in?"

The priest, unshaven, had ballooned to 250 pounds. Years of fear fell away as Mark stood in the dimly lit room. His parents sat on the couch, Hanley in a reclining chair.

"You raped me of my innocence, you stole my childhood!" Mark declared. "You used the guise of the cloth and the word of God to control me and your victims so you could use us for your selfish, demented needs. You took a child, a little boy, not the thirty-year-old man you see in front of you—a child who didn't know what sex was."

Hanley looked up, as if in a daze.

"In the presence of God almighty," said Mark, "and for the sake of the destiny of your soul—who were the last victims ... their names, and where they live?"

"As far as I know, Mark," Hanley said, "you were the only one."

"You ever hear of Billy Crane?" replied Mark.

"Yeah," said Hanley, gazing downward.

"Kindly face me, Jim," Pat said. "You took a child away from me. You ruined aspects of my life.... You have bodies of boys littered all over Mendham." She called out the names of mothers whose sons he had molested. "You said, 'Come and be a Eucharistic minister, Pat.' That was a payoff, Jim! What are you paying off with now?"

Hanley was silent.

Lou Serrano spoke like the cop he had once been: "There is no place you can hide.... I will hound you, Jim. You are a pedophile. You prey on children."

"Nothing's happened since Mendham," whispered Hanley. "To the best of my memory..."

Mark's gaze fell to the floor beside the priest's chair, and he recognized a familiar object.

"You're using the same vibrator!" he cried.

Hanley looked away.

THE TORRENTS OF RECENT media coverage triggered by the Boston Globe's reporting of pedophile-priest cover-ups emboldened many victims to speak out. Few have had the impact of Mark Serrano. Disregarding the non-disclosure agreement he signed, Serrano gave interviews to the New York Times [see the article] and Oprah, which prompted more St. Joe's boys out into the open. A homeless man in Morristown, New Jersey, who lived in a concrete conduit, telephoned Serrano, sobbing, remembering Father Jim. Bill Crane called from Clackamas, Oregon. "I sat in my living room holding my wife's hand, watching television, and I heard my story come from your mouth," he said.

On April 19th, as eleven American cardinals began leaving for Rome to hold discussions with Pope John Paul II about the crisis, Mark Serrano convened his own summit. He returned to Mendham to meet with eight other men whose childhoods had been tormented by Father Jim.

Serrano had asked Hanley's former superior, Bishop Rodimer, to attend the final session and hear the stories of the survivors. In 1985, Rodimer had removed Hanley as a working priest once the accusations arose, but he never reported him to police. (Hanley, 65, is now retired and lives in Paterson, New Jersey. Attempts to contact him for this article went unanswered.)

At 5:30 P.M., the bishop entered the conference room at the St. Joseph parish center for the meeting. He sat opposite nine of the men who had been abused by Hanley. A poster showed photographs of them as boys.

This was not the first time Rodimer's vigilance against pedophile priests had ever been challenged. In 1999 he had settled out of court with a sex-abuse victim of another priest, the Rev. Peter Osinski, who shared a rented house at the Jersey shore for more than twenty years with Rodimer. Osinski eventually went to prison for the abuse. The Paterson diocese paid a reported $250,000 in a suit against Rodimer for failing to notice or put a stop to the assaults.

"You're responsible," said Tom Crane—Bill's twin, who had also been abused by Hanley. "What are you going to do about it? Hanley is a pedophile. You think there is a cure?"

"I don't know," said the bishop. "I don't think—"

"You have the power, Frank, to do something before you retire," said Tom. "This man belongs behind bars."

The bishop frowned. "What are you proposing?"

Groans went up around the room.

Serrano demanded that Rodimer publish a photograph of Hanley in the diocesan newspaper with the words WANTED: RECENT VICTIMS OF JIM HANLEY.

The room erupted in applause.

"I don't have the right to put him behind bars," said Rodimer.

By the end of the meeting, nothing had been resolved or even fixed. Still, in the thirty days since he had gone public with his story, Mark Serrano had gone from anonymous victim to crusading survivor.

"I got a piece of my childhood back," said Bill Crane.

"We did something good today," Serrano said.

*

JASON BERRY is the author of "Lead Us Not Into Temptation," among other books.

[Note on the text: This Web version was scanned by BishopAccountability.org from a paper copy of the June 20, 2002 Rolling Stone magazine, and was checked against the original.]

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.