Hiding in Plain Sight

Great Escapes

Cleric Slips Out of U.S., Continues to Work in Mexico

|

| 'Everyone knew you had to stay away from Aguilar.' |

By Brooks Egerton and Brendan M. Case

Dallas Morning News

June 22, 2004

[See also Egerton on the human

toll of Aguilar's alleged abuse and a timeline

with documents, showing Aguilar's travels and the protection he enjoyed.

See a list of articles

in the series. For diocesan and legal documents on Aguilar and links

to articles, see the BA.org webpage on The

Aguilar Case.]

http://www.dallasnews.com/sharedcontent/dws/news/

longterm/stories/062204propriestpt3.1db08.html

The Mexican bishop had trouble on his hands. An attacker had nearly killed

one of his priests, whose sexual misconduct was well known to the bishop.

And now villagers were telling police about a stream of young male visitors

to the priest's parish residence.

The U.S. bishop had a different problem: a lack of Spanish-speaking priests to serve a growing immigrant population.

And so, in 1987, the Rev. Nicolás Aguilar got a fresh start in Southern California. Just nine months later, he was on the move again, leaving behind one of the largest child sexual abuse cases in Los Angeles Archdiocese history. Again, scandal was contained with the priest hiding abroad.

|

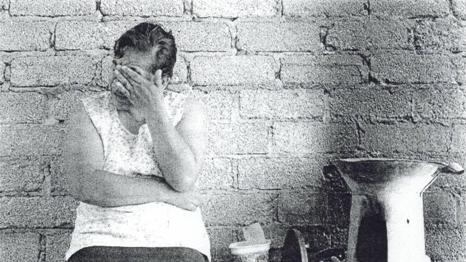

| "I felt like someone had poured boiling water on me when I found out," said María de Jesús González, the mother of a 12-year-old boy in Mexico's Tehuacán Diocese who accused the Rev. Nicolás Aguilar (top) of molesting him in 1997. |

|

| [In the News' Web posting of this article, the photo of Aguilar was superimposed on that of Ms. González.] |

Father Aguilar's tale of international flight fits a pattern that Catholic Church leaders have repeated around the world, a yearlong Dallas Morning News investigation has found.

In this case, the two bishops have become prominent figures in the global Catholic hierarchy. One, the Rev. Norberto Rivera, is now Mexico City's cardinal and one of his country's most powerful men. The other, Los Angeles Cardinal Roger Mahony, leads the largest diocese in the United States.

Father Aguilar is more than just an old skeleton in their closets. After dodging criminal charges in California, where police said he had molested at least 26 boys, he was charged in a 1997 Mexican abuse case. Church leaders kept him in ministry while the matter was pending and even after his conviction in 2003. Recently, he was spared punishment on a technicality, a Mexican judge said.

Cardinal Rivera did not respond to The News' written requests for information about the priest. Asked after a recent Mass what had become of Father Aguilar since his return to Mexico, the cardinal said: "I'm absolutely ignorant." He would not elaborate.

Cardinal Mahony declined to be interviewed. Spokesman Tod Tamberg did not respond to most questions from The News, although he did say that Father Aguilar was accepted in Los Angeles after Cardinal Rivera wrote that his cleric wanted to move there "for reasons of his family and health."

Father Aguilar, in a brief interview at a courthouse in Tehuacán, 150 miles southeast of Mexico City, denied any wrongdoing.

"God knows," he said, "that this is all just a slander to destroy me."

Numerous documents and interviews with former parishioners suggest otherwise.

In a Tehuacán slum, Catalina Cortez recalled how she let her 11-year-old son visit Father Aguilar's house on Saturday afternoons in 1997 to prepare for his first communion. She knew nothing about the priest's past.

"Aguilar would come to our home and ask that the kids go with him and sleep over," said Ms. Cortez, whose son was one of four boys who later reported abuse allegations to police. "I tried to respect his wishes, because he was a priest and I'm just an ordinary person."

Allegations since '70s

Lay people, ranging from a seminary student to parishioners to police, have long tried to stop the 62-year-old Father Aguilar.

Allegations of sexual abuse against him first began surfacing in the 1970s, according to Jorge Cadena, a former high school student at the Tehuacán junior seminary. He said one classmate told him that Father Aguilar had attacked him.

"Everyone knew you had to stay away from Aguilar," said Mr. Cadena, who is now an engineering professor at a nearby technical school. "But when I complained to the priests in charge, they kicked me out of school."

In 1986 or early 1987, when Father Aguilar was heading a parish in Cuacnopalan, near Tehuacán, someone nearly killed the priest. One Saturday night, residents found him at the church residence in a pool of blood.

He'd been bludgeoned with a club or slashed with a bottle or shot, depending on the account. There are no public records of the crime, which went unsolved. Authorities said Father Aguilar didn't want it prosecuted.

Miguel Pérez, a church neighbor who served as a local sheriff at the time and said he helped investigate, suspected that Father Aguilar had been attacked by one or more guests.

"On weekends, the priest always had visitors, young men and teenagers who would spend the night," said Mr. Pérez, who still lives across from the church.

Father Aguilar said the attack stemmed from a land dispute involving a lot next to the church. His neighbors, he recalled, "said they'd never leave me alone."

New job in East LA

By April 1987, the priest had transferred to Our Lady of Guadalupe parish in East Los Angeles.

After about two months, he was transferred again, to St. Agatha in South Central Los Angeles.

Father Aguilar maintained ties with families at the first parish. And by December 1987, two young altar boys there were telling their mother that Father Aguilar had been molesting them.

She contacted Our Lady of Guadalupe's head priest. He begged her to stay quiet, she said. The head priest also alerted the cardinal's head of clergy personnel, Monsignor Thomas Curry.

Meanwhile, the woman's husband contacted another couple Father Aguilar had befriended. Soon, their boys also were saying that they had been abused.

On a weekday in early January 1988, their mother called the parish school, whose principal notified police the following Monday morning.

It was too late. Monsignor Curry – who is now a bishop and still working for Cardinal Mahony – had advised Father Aguilar of the allegations at least two days earlier and suspended him.

Father Aguilar had told Monsignor Curry he would return to Mexico, according to police reports. But the monsignor did not notify authorities of the priest's plans. Meanwhile, Father Aguilar had a local relative drive him to Tijuana.

Later, Sister Judith Murphy, a nun who was Cardinal Mahony's in-house lawyer for 17 years, refused police requests for church records.

"My biggest problem was the stonewalling of the Catholic Church," said Gary Lyon, lead detective on the Aguilar case, who has since retired.

Added Janice Maurizi, a Los Angeles prosecutor, "The archdiocese facilitated his flight."

No criminal charges accusing anyone of a cover-up have been filed in this or any other Los Angeles clergy abuse case. But the district attorney's office is investigating the possible "criminal culpability of anyone in the hierarchy of the archdiocese" who dealt with abuse accusations, said prosecutor William Hodgman, who heads the inquiry.

The cardinal's spokesman, Mr. Tamberg, declined an opportunity to respond to the statements from law enforcement officials.

'The number is large'

After Father Aguilar left Los Angeles in 1988, Cardinal Mahony wrote Cardinal Rivera, asking him to cooperate with detectives. Cardinal Mahony described his request as "very urgent," although he had waited two months to send the letter.

"It is almost impossible to determine precisely the number of young altar boys he has sexually molested, but the number is large," Cardinal Mahony wrote. "This priest must be arrested and returned to Los Angeles to suffer the consequences of his immoral actions."

Cardinal Rivera provided the names of Father Aguilar's parents and his hometown, but little more. He also pointed his U.S. counterpart to Cuacnopalan, scene of the violence against the priest.

"You will understand that I'm not in a position to find him, much less force him to return and appear in court," wrote Cardinal Rivera, in a letter dated March 17, 1988. "I can tell you that the priest was in San Sebastián Cuacnopalan parish for over 10 years, and surely the police there can find much information."

Cardinal Rivera also reminded Cardinal Mahony that he had given him, when sending Father Aguilar to Los Angeles, "a summary of the priest's 'homosexual problems.' " (Click the links about to read the full text of the letters.)

That term is "code for having been caught with young boys," said the Rev. Thomas Doyle, a former official with the Vatican's embassy in the United States, who has reviewed many abusive clergymen's personnel files. He said top church leaders generally don't consider consensual adult homosexuality a problem, despite their public statements to the contrary.

Cardinal Mahony wrote back to Cardinal Rivera, saying "we do not admit priests with any homosexual problems." He said he had never received the warning and asked Cardinal Rivera to send it again. Cardinal Rivera did not do so and has not replied to more recent requests, according to Cardinal Mahony's spokesman. The Mexican cardinal also did not respond to The News' request for a copy of his letter.

The letters that The News did obtain came from Los Angeles criminal case files in response to an open-records request from the newspaper.

Cases go nowhere

By the time the bishops were corresponding in 1988, Los Angeles detectives were wrapping up their investigation.

The district attorney's office, seeing no sign that the church was going to return the priest and fearing that he wouldn't be extradited, submitted its 10 strongest cases for prosecution in Mexico. (That country's legal system allows Mexican citizens to be prosecuted at home for crimes committed abroad.)

The cases went nowhere.

Enrique Zepeda, the top lawyer at Mexico's consulate in Los Angeles, said Los Angeles police did not produce legally required evidence that the suspect was from Mexico. Likewise, no evidence showed that Father Aguilar was a priest, said Mr. Zepeda, who did not handle the case at the time. He and his bosses in the Mexican attorney general's office would not release supporting documents.

But readily available Mexican church records show that Father Aguilar was born in Mexico and ordained to the priesthood there, and that he has spent most of his adult life in clerical assignments in that country.

Los Angeles police say Mexican officials never expressed concerns about verifying Father Aguilar's nationality and clerical status. The Mexicans usually obtain such documents themselves, said Detective Fernando Gonzalez, who serves in the Police Department's foreign prosecution unit and worked on the Aguilar case.

The unit's records indicate that Mexican authorities did ask three times for the accusers' birth certificates, promptly received them in each instance and reported losing them at least once.

In 1995, Mexican prosecutors finally took the case to a judge, who dismissed it as too old to prosecute.

"I don't know what happened in Mexico," Detective Gonzalez said. "I can't tell you if it was planned or it just happened."

|

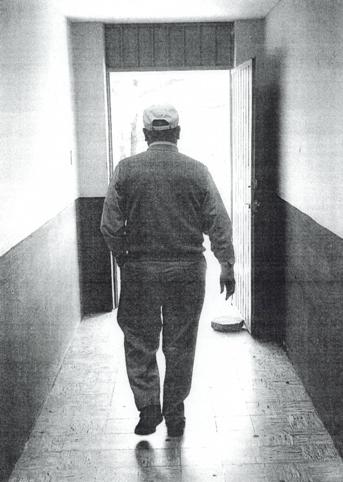

| Father Nicolás Aguilar leaves a court building in Tehuacán, 150 miles southeast of Mexico City, where he had to sign a bail book every Friday while appealing his molestation conviction. Photos by Erich Schlegel / Staff Photographer. |

|

Ms. Maurizi, who oversees prosecutions in Mexico for the Los Angeles district attorney, said she complained repeatedly to Mr. Zepeda's predecessor. About two years ago, she finally got him to admit what had happened, she said.

"The system was never going to prosecute a priest," she said the predecessor, Jorge García-Villalobos, told her.

Mr. García-Villalobos, now working in the private sector in Mexico City, said he was merely pointing out that prosecuting a priest would be difficult in any country – let alone Mexico, which has a large Catholic majority. But he did not say it would be impossible, he said.

At Ms. Maurizi's urging, Mr. García-Villalobos recommended a federal inquiry into why the California charges hadn't been prosecuted swiftly and whether the priest might have committed more crimes in Mexico. He and Mr. Zepeda said they don't know what became of the recommendations.

|

| Roger Mahony |

The dismissal of the Aguilar case is unusual. Authorities on both sides of the border say almost all foreign prosecutions in Mexico end in convictions.

The only similar case The News could find – of another priest who was supposed to face trial in Mexico on molestation allegations from California – also languished for years and finally was dismissed as too old.

One boy's story

In 1995, the year the California allegations were dismissed, Father Aguilar was listed in a church directory as serving in a Mexico City parish. The archdiocese also got a new leader that year: Cardinal Rivera.

But by 1997, Father Aguilar was back in his home Diocese of Tehuacán, working on the outskirts of town. His base was the chapel of San Vicente Ferrer, a spare, concrete building in San Nicolás Tolentino Parish.

One day, a 12-year-old boy who'd become active in the parish ran away. His frantic parents found him at a relative's house 75 miles away, where he'd gone by bus with a 14-year-old friend.

The son told his father why he ran: Father Aguilar had been molesting him for months, according to the boy's statement to police. Soon, his friend and two other boys said Father Aguilar had abused them, too.

"I felt like someone had poured boiling water on me when I found out," said the 12-year-old's mother, María de Jesús González.

Father Aguilar had chosen her son as the leader of a group studying for first communion. The priest lavished special attention on the boy, often asking him to stay behind when the other kids left, according to police reports.

"Father Nicolás told me that what I was doing with him was normal, between men, that some people did that," the boy told police, in a statement obtained by The News.

The priest also threatened to kill the youngster's mother or his younger brother if he told anyone about the abuse, according to court documents and interviews.

Ms. González marched all four kids to the police station to make statements after she learned of the accusations. She repeated the allegations in a radio interview. And "people here told me they were going to lynch me for denouncing a priest," she said.

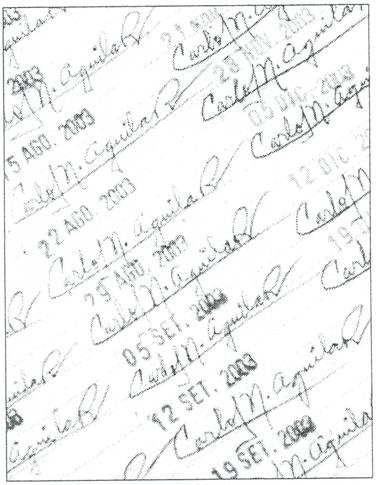

She didn't back off, and the case went forward – sort of. In 2003, six years after the initial complaints, state Judge Carlos Ramírez found Father Aguilar guilty of a misdemeanor abuse charge based on allegations by a 14-year-old.

Judge Ramírez sentenced Father Aguilar to a year in prison, but the priest remained free on bail while appealing the decision to federal court. Federal judges recently let the conviction stand but spared Father Aguilar punishment on the grounds that the crime was too old, Judge Ramírez said last week.

Yet it was Father Aguilar himself who had delayed the case, the judge said, by waiting four years to appear in court and answer the charges.

Earlier, Judge Ramírez had dropped a felony charge against Father Aguilar for corruption of minors. "The psychological exams on the supposed victims did not show signs of sexual abuse," he said.

But that's not what police psychologist Bibiana Rojas wrote in her report, a copy of which was obtained by The News. After questioning Ms. González's son on Dec. 20, 1997, Ms. Rojas found "aftershocks of severely traumatic experiences of a sexual nature."

Judge Ramírez said criminal investigators never showed him the report. The lead investigator declined to comment.

The four boys weren't the only victims, Ms. González said. She said she spoke with a dozen mothers who urged her to drop the charges against Father Aguilar – even as they told her their own sons also had been abused.

A Tehuacán Diocese official said that Father Aguilar had abused about 60 kids, according to Ms. González. She said the Rev. Teodoro Lima told her this in explaining why the church couldn't afford to pay for her son's counseling.

Father Lima told The News he didn't remember the conversation. He also said Father Aguilar had never returned to Tehuacán after going to California.

Cardinal's dueling views

Cardinal Rivera, now the leading face of the Catholic Church in Mexico, has sent mixed signals on sexual abuse.

In 2002, when several prominent bishops criticized suggestions that the church should hand over accused priests to police, the cardinal scolded them. "When these criminal abuses occur, inside or outside the church, of course they should be reported to authorities, and justice should be done," he said in a televised sermon.

But he also told the Italian Catholic journal 30 Giorni in 2002 that "as far as I am aware, there has not been any documented report" to Mexican authorities of a priest molesting children.

Meanwhile, protests over the Aguilar case have gone all the way to Mexican President Vicente Fox.

In a July 2003 letter to the president, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., complained that the priest had gone free because "Mexican prosecutors failed to submit the case for timely prosecution."

Father Aguilar's case was one of several she cited as evidence that Mexico was not aggressively tracking down people accused of fleeing there after committing crimes in California.

Mr. Fox never responded, Ms. Feinstein's office said. His aides did not respond to requests from The News for comment.

In Los Angeles, Cardinal Mahony portrays himself as a reformer who doesn't tolerate sexual misconduct. Pending lawsuits, which he is contesting, allege that he concealed abuse by several priests and religious brothers.

About 250 priests and brothers have been accused of molesting children in the Los Angeles Archdiocese over the last 75 years, though many have been publicly named only in the last year.

"The unique feature of the Aguilar case is how dramatically it shows the international trafficking of sex abusers in the Catholic Church," said Raymond Boucher, whose law firm represents three alleged victims of Father Aguilar and hundreds of other accusers.

Cardinal Mahony is fighting in court to withhold clergy personnel files from prosecutors and plaintiffs' lawyers, citing the priests' privacy rights.

His resistance has done "little to enhance the reputation of the church in the United States for transparency and cooperation," according to a recent report on American dioceses commissioned by U.S. bishops.

Fallout

Father Aguilar still haunts the four Tehuacán boys who accused him of abuse.

One was recently allowed to move back into his parents' house on the condition that he never speak of the abuse. Another, now 21, migrated illegally to North Carolina. Catalina Cortez's son moved to Guadalajara.

Ms. González's son has left, too, after one too many taunts by kids and townspeople. He is 19 now, and his mother says she isn't sure where he is.

"This whole case has been pretty much forgotten around here," she said. "But our son won't forget. We won't forget either."

As for Father Aguilar, he has worked in at least five Mexican dioceses since leaving Los Angeles. While the Tehuacán case was pending, he went back to parish duty in Mexico City working for Cardinal Rivera before moving to a post at the cathedral in the Ciudad Lázaro Cárdenas Diocese, according to records and interviews.

In recent years, Father Aguilar also has worked informally in the Puebla and Cuernavaca dioceses.

"Some of my fellow priests have offered the charity of letting me live with them," he said, adding that he still formally belongs to the Tehuacán Diocese.

"I don't spend too much time in any one place."

Staff writer Brooks Egerton reported from Southern California and Dallas; staff writer Brendan M. Case reported from Mexico City and the nearby state of Puebla. News assistant Javier García in Mexico City contributed to this report.

E-mail begerton@dallasnews.com and bcase@dallasnews.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.