Nun says Christian response goes beyond innocence or guilt

By Jeannine Gramick

National Catholic Reporter

January 14, 2005

http://ncronline.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2005a/011405/011405n.php

I was anxious as I boarded the plane to Boston to see Paul Shanley, a priest accused of pedophilia, made notorious by The Boston Globe and the national media. What would we talk about after all these years? I didn’t want to quiz him about the lurid stories I had read. I didn’t want to ask, “Paul, did you do these terrible things?” I was hoping he would sense that I just wanted to offer him the comfort of friendship.

[PHOTO REDACTED]

|

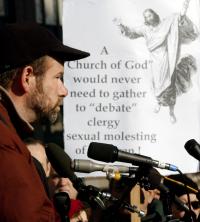

| Fr. Paul Shanley looks on during his extradition hearing in San

Diego May 3, 2002. The priest, no longer active, was arrested the

day before in San Diego and faces child rape charges in Newton, Mass.,

from alleged incidents in the 1980s. CNS/Reuters |

I met Paul, who is scheduled for trial Jan. 24, in the early 1970s at a conference in Dayton, Ohio, about ministry to homosexual persons. Over the years, we would minister together in various ways. We marched to the Detroit chancery to protest the diocesan newspaper’s firing of Brian McNaught, a gay man and youth columnist. We demonstrated for gay and lesbian civil rights legislation in Wichita, Kan., at the height of Anita Bryant’s anti-homosexual campaign. We spoke at meetings for lesbian and gay Catholics, presented workshops to sensitize heterosexual Catholics about homosexuality, and prayed publicly that our society and church would acknowledge that lesbian and gay persons need make no apology for their sexual orientation.

|

| Sr. Jeannine Gramick CNS |

I knew Paul to the extent that one knows most colleagues in ministry. I understood him as a person who shared my vision of justice for the oppressed. I experienced him as an iconoclast who publicly denounced social, medical or ecclesial institutions that kept the underdog continually underneath. I admired this man who reminded the establishment what it was established for -- service to individuals, not self-preservation. I was proud to be acquainted with him and call him a friend.

But for many months following the public revelations of his alleged abusive actions, I felt uneasy acknowledging I knew Paul, as if my association with him would imply I had little sympathy for victims of sexual abuse. Of course, I was appalled and horrified by the sexual violations against our young or not so young by persons in positions of trust. At the same time, my heart grieved for this man I had not seen in almost 20 years, but whose principles and whose advocacy for the downtrodden I had applauded for three decades.

In April 2002, when the press branded Fr. Paul Shanley a pedophile, I was shocked and grieved. The images of his being handcuffed and arrested at his apartment in San Diego, shown on the TV news networks and magazine shows, played like continual reruns in my mind. I found myself wondering why Paul had done these things, what had he been thinking and feeling, why hadn’t we, his friends and colleagues, sensed that he was troubled? Perhaps some action on our part could have helped preclude this terrible tragedy. Like most people, I assumed he was guilty of the horrible acts attributed to him.

I e-mailed these ruminations to Brian McNaught, a friend, respected educator and author, who had stayed in closer touch with Paul since the story broke. Brian reminded me, as The Boston Globe had editorialized, that the accused should be presumed innocent until proved guilty. I had fallen into the easy trap of a negative judgment because of unproved allegations. Even if Paul were found guilty, Brian maintained, Paul was and would remain a friend.

When Paul surrendered to the civil authorities in May 2002 to face child rape charges in Massachusetts, he was remanded to the Middlesex County Jail in Cambridge. I wrote to assure him of my concern. I worried about his mental health and how he was coping with this dreadful ordeal. I did not want him to feel alone or abandoned. Moreover, somewhere deep within me came a nagging feeling that I should see Paul. I wanted to tell him in person, no matter what charges -- whether true or false -- had been leveled against him, that I cared about him.

I learned that, if I wanted to see Paul, I should contact Terry, his niece, who scheduled his visitors. He was allowed half-hour visits every Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. After several phone calls with Terry and the requisite paperwork for the jail supervisor, I was cleared for two visits.

The Cambridge jail

My anxiety was somewhat allayed as I lunched with Terry in the mall near the county jail. She believes her uncle, who has been like a father to her, is innocent. The four individuals who have brought indictments against Paul all base their claims on repressed memories, a concept regarded with skepticism by leading mental health professionals. Terry believes there is not sufficient evidence to convict her uncle. Furthermore, her uncle told her he had never raped a child or forced anyone to engage in sexual acts, and he would not lie to her. If he were guilty, would he have given himself up to the district attorney’s office? Why do people believe all the allegations without proof? she asked.

After lunch, Terry accompanied me to the visiting quarters of the Middlesex County Jail, the 17th floor of a high-rise building near the Charles River as it curves its way toward downtown Boston. After checking in, completing the visitor information form, and a brief wait, I surrendered my driver’s license and placed my belongings in a wall locker. With a loud clang, the first metal door opened. After passing through the metal detector, I heard another grating sound and the second metal door opened. As I entered the room to the left, Paul was standing behind a glass partition.

My inability to give him a hug or even touch his hand reassuringly did not diminish the pleasure or satisfaction I felt in seeing him after such a long hiatus. The smile of his eyes said he felt the same. Health problems and his 71 years had taken their toll on the man I remembered from 20 years ago.

He told me that one of the difficult aspects of his detention was the danger of physical beatings from other inmates. The length and severity of beatings are commensurate with an in-house hierarchy of heinous acts: sexual abuse of minors, murder and assault of the elderly. Paul was in protective security. But the horrible murder of convicted pedophile and former priest John Geoghan is a sad testament that detention in “protective security” is neither protective nor secure.

Buoyed by my visit, Paul seemed in good spirits. We reminisced about the beginning days of the movement for gay rights and recalled mutual friends. Even though some former parishioners, one Boston priest, his relatives, and a few friends visited him, most of his friends and professional colleagues had not contacted him. “I don’t blame them,” he said. “I don’t know what I would do.” The archdiocese sent a deacon with laicization papers for Paul to sign. “I wouldn’t sign them,” he said. “Good!” I said. I asked myself, “What loving family or community would abandon a member because he or she was accused of a heinous crime?”

Paul and the 15 other inmates on his tier played cards, watched TV and enjoyed a warm camaraderie. His companions on the tier believed he was innocent. More important, so does his lawyer. We spoke only minimally about his case.

On my succeeding visit two days later, I brought up the frequent and damning reports that Paul endorsed sex between men and boys and that he founded the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA). Roderick MacLeish Jr., the lawyer representing the plaintiffs against Paul Shanley, originated the charge in a two-and-a-half-hour news conference, televised live in Boston. MacLeish publicly distributed Paul’s archdiocesan file as “proof.” An examination of the file, however, does not substantiate MacLeish’s assertion.

The allegation is based on a 1978 article, which reported that Paul spoke at a conference about the legal aspects of sex between men and teenage boys. The conference was not a meeting of the association, which did not exist at the time. Paul was only one of many speakers, including lawyers, psychologists, ethicists and activists. The article did not state that Paul advocated man-boy sexual relations. In fact, his file contains written testimony to the contrary. He does not condone the sexual seduction of children. After the conference, some participants decided to form a Man-Boy Love Association at a caucus Paul did not attend.

I told Paul I was glad to see this explanation in a letter to the editor of The Boston Globe. The letter writer went on to say, “The portrayal of a legitimate public forum as somehow sinister, associating it with a stigmatized group that did not yet exist, and linking Shanley to it in an effort to strengthen the allegations against him is irresponsible and gets in the way of finding the truth.” Paul sadly shook his head and said, “Yes, and shortly after the letter appeared, the Globe ran another story naming me as the founder of NAMBLA.”

During our two meetings, I found him outer-directed, asking about our mutual friends, and interested in how I was. Of course, all this could have been a brave front. But at least for the time I was with him, Paul was enthusiastic and not bitter, which was a saving grace. He realized that his good name, like his life’s savings spent on lawyers’ fees, would never be recovered.

Paul repeated that there must be some reason for what had happened to him and expressed a desire to help all priests accused or convicted of child molestation. We prayed together the words of St. Paul in Romans 8:28: “For those who love God, all things work together unto good.”

As I rose to leave, I was conscious that the glass partition blocked the hugs I wanted to give him. So I used Terry’s departure ritual with her uncle. With my index finger, I pointed to my chest, then to my heart, and then to Paul. Smiling broadly, Paul did the same.

During the interval between my visits to the Cambridge jail, I stayed with friends in the area, one of whom has reported extensively about the sexual abuse scandal in Boston. Listening to him reiterate what had appeared in the press, I felt Paul was guilty. But listening to Terry and to Paul himself, I felt Paul was innocent. Paul may be guilty or innocent of the present charges of sexual abuse of children. Paul may be guilty or innocent of other allegations involving young adults. But guilty or innocent of sexual misconduct or even pedophilia, Paul is my friend. I believe that no person is completely faultless or totally depraved. I believe that no private or public incriminations can erase the good Paul Shanley has effected in the lives of thousands of people, our church and the greater society.

After seven months in jail, Paul was released on bail, amid demonstrations, name calling and media hounding. He lives at an undisclosed location in Massachusetts. I have visited him several additional times and try to keep in regular phone contact with him.

Trying times

In April 2004, the Boston archdiocese, under Archbishop Sean O’Malley, settled monetarily with the four men who accused Paul Shanley of sexual abuse, despite the fact that no credible evidence was presented in a civil or ecclesiastical court. Paul was not given an opportunity to respond. It seems to me that the hierarchy is operating by the same principle it exercised decades ago when it kept clerical misconduct a secret, that is, protecting the institution, not individuals. Today many financial settlements are made without recourse to just procedures of examination. The search for truth appears secondary to protecting the institutional church from the criticism of insensitivity to alleged victims of sexual abuse.

|

| John Harris, allegedly abused as a child by Paul Shanley, speaks to protesters outside the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston Dec. 8, 2002. CNS/Reuters |

The following month, the Vatican, by request of the Boston archdiocese, defrocked Paul Shanley, removing him arbitrarily from the priesthood. The hierarchy afforded him no ecclesiastical trial, presented no specific charges, no names of accusers, no evidence and no opportunity to tell his story. In Paul’s case, as in many others, the right of the accused to a fair procedure was nonexistent.

In July 2004, Massachusetts state prosecutors dropped the charges of the most outspoken accuser, Gregory Ford, from their criminal case against Shanley. They judged Ford’s allegations too risky or unsupportable. The charges made by Anthony Driscoll were also dropped. Those close to the legal proceedings say a third case, by someone retaining anonymity, will also soon be dropped. The only remaining charges are from Paul Busa, who claims recovered memories after hearing about Ford’s allegations in the newspapers. The developments in the case, which appear in Shanley’s favor, barely elicited an acknowledgment from even the Boston media.

My reconnection with Paul Shanley has made me realize that the clerical abuse crisis is more than a problem of exploited children and youth, sick or sinful or falsely accused priests, and cover-ups by bishops. It is a problem that cannot be resolved merely by seeking redress in the secular legal system. It is a problem whose healing needs a community ready to acknowledge human weakness and sin, to humbly beg forgiveness and seek reconciliation, and to extend nonviolent love toward those who knowingly or unknowingly cause harm.

Because many victims of sexual abuse did not find understanding, compassion and justice from church leaders, they understandably sought recourse in secular courts. But the legal route has ushered in new injustices. While visiting Paul, I received overnight hospitality one evening with a religious community whose former provincial told me an illustrative story.

More than 20 years ago, when this former provincial had been a school principal, a mother complained to him that a teacher, one of his community members, had molested her son. As a principal, he responded caringly by listening to, and sympathizing with, the mother and her son and seeing that both the youth and the teacher received psychological treatment at the community’s expense. He kept in frequent touch with the mother to inquire about her son’s condition, but ceased communication after he was assured the son had healed. In late 2002, the religious congregation received notice from the mother and son’s lawyer that the congregation was being sued for sexual abuse of a minor. Twenty years ago, the family was apparently satisfied with the community’s response. Sinful and harmful behavior occurred, as did restitution and healing. Lawyers have now persuaded the family to demand additional compensation, thus diverting financial resources from the good works of the religious community. This is not the Christian notion of reconciliation.

I can’t help wondering if lucrative business interests are spurring the current legal actions. Such litigation, with its astronomical demands, may be bringing new offenses. In the June 9, 2003, issue of Forbes, Daniel Lyons harshly criticized litigators, including Roderick MacLeish Jr., who have “parlayed the priest crisis into a billion-dollar money machine, fueled by lethal legal tactics, shrewd use of the media and public outrage so fierce that almost any claim, no matter how bizarre or dated, offers a shot at a windfall.” Lyons goes on to say that overdue justice could lead to a “legal morass marked by extortion as much as fairness, in which a small cast of liars cashes in on the real suffering of victims.”

Many Catholics in the pew are becoming concerned about the financial drain from the church’s coffers -- economic resources that come from the whole community for the service of all, especially the poor. Unfortunately, several dioceses have declared bankruptcy and others have been forced to lay off church workers and diminish their outreach to the needy in order to settle sexual abuse cases.

A Christian response

As long as we view this crisis solely in terms of crime and punishment, I believe we fail to make a Christian response. We need to acknowledge the church is a sinful as well as loving community. A Christian community is a place where our sins can be exposed and repented, where we can confess our faults and be transformed by others’ forgiveness. It is a place where kindness and compassion are extended and received.

I believe Christian compassion needs to be offered to the alleged abuser as well as to victims of sexual abuse. No matter if we think Paul Shanley is innocent or guilty of the charges against him, the Christian response requires empathy and understanding. There was never any pastoral visit from the Boston archdiocese to Paul Shanley. Some of Paul’s friends have suffered repercussions. One, a Boston area professional whose picture was taken with Paul in the courtroom, was subsequently informed his political career in Boston was ended. Another friend had two speaking engagements canceled when the inviting groups discovered the lecturer was Shanley’s friend. How can such actions be squared with the Gospel’s mandate of visiting the imprisoned?

The imprisoned and convicted pedophile priest John Geoghan was brutally murdered in his prison cell at the Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center outside Boston. If convicted, Paul would be serving a sentence at the same prison where Geoghan was bound, beaten and strangled. At this correctional facility, as well as others, guards often permit prisoners to act on their aggressive feelings toward child molesters.

How can we stop this horrific cycle of violence? When will we understand that each person is a blend of good that mirrors the divine and evil that needs redemption? Have we heard preached any words of compassion for the known abuser and alleged abuser? When will we learn how to balance justice, accountability, rehabilitation and reconciliation?

I grieve profoundly for our church and ask God to heal this terrible wound that has punctured us all.

Perhaps the most challenging part of Christ’s message for us to understand and imitate are his words from the cross about his torturers, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

Jeannine Gramick is a Sister of Loretto known for her work with lesbian

and gay Catholics.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.