A Priest's Story—Part

II

Given probation after his signing of a confession, Fr. MacRae took a job at a center for priests in New Mexico, where he received, one day, a strange letter from a Jon Grover, now in his mid-20s—a member of a family he had known well back in Keene, N.H. The letter-writer referred to many sexual encounters in detail, and observed that "the sex between us was very special to me." The priest wrote back that the writer must be an imposter, since the real Jon Grover would have known that no such thing had taken place. It was the first of several sting attempts by Detective James McLaughlin, whose own reports testify that he wrote the letters himself. Jon's older brother Thomas—now, like his brother, deep into plans for a civil and criminal case alleging that the priest had molested him a decade earlier—took a role in a different sting effort. This was a series of phone calls to the priest, which Detective McLaughlin was supposed to record. It was no small testament to the primary goal of all these efforts that those calls originated—as the phone records show—from the office of Thomas Grover's personal-injury lawyer. The possibilities of a lawsuit caught the attention of an increasing number of Grovers: 27-year-old David Grover informed police, in 1992, that when he heard a report of financial settlements in the notorious Father James Porter case in Massachusetts, he had had to pull his car over and weep, because he had been overcome, suddenly, by his memories of his victimization by Fr. MacRae. * * * In early May 1993, while in New

Mexico, Fr. MacRae was arrested on the basis of indictments in New

Hampshire. He now faced criminal charges from Lawrence Carnevale,

Jon Grover and Tony Bonacci, who chose to leave the country to avoid

testifying. There would be, in the end, just one trial—on

accusations by Thomas Grover that the priest had assaulted him sexually

during counseling sessions in a rectory office, and elsewhere. If the events leading to Fr. MacRae's prosecution had all the makings of dark fiction, the trial itself perfectly reflected the realities confronting defendants in cases of this kind. For the complainant in this case, as for many others seeking financial settlements, a criminal trial—with its discovery requirements, cross-examinations, and the possibility, even, of defeat—was a highly undesirable complication. The therapist preparing Thomas Grover for his civil suit against the diocese sent news, enthusiastically informing him that she'd had word from the police that Gordon MacRae had been offered a plea deal he could not refuse, and that the client could probably rest assured there would be no trial. On the contrary, Fr. MacRae would over the next months refuse two attractive pretrial plea deals, the second offering a mere one to three years for an admission of guilt. Throughout his testimony, Thomas Grover repeatedly railed at the priest for forcing him to endure the torments of a trial. He would not have much to fear, in the end, in these proceedings, whose presiding judge, the Hon. Arthur D. Brennan, refused to allow into evidence Thomas Grover's long juvenile history of theft, assault, forgery and drug offenses. In New Hampshire, where juries need only find the accuser credible in sex abuse cases, with no proofs required, this was no insignificant restriction. The judge also took it upon himself to instruct jurors to "disregard inconsistencies in Mr. Grover's testimony," and said that they should not think him dishonest because of his failure to answer questions. The jury had much to disregard. The questions he did answer yielded some remarkable testimony related to the central charges—that in the summer of 1983, at age 15, he had been repeatedly assaulted sexually by the priest, in four successive counseling sessions in the rectory office and another time elsewhere. Confronted with inevitable questions about why he would come back, after the first terrifying attack on him, for a second, third and fourth session, Mr. Grover told the court that he had an "out-of-body experience." Also that he had blackouts that caused him to go to each new counseling session with no memory that he had been sodomized and otherwise assaulted the session before. Such attacks during counseling (sessions Fr. MacRae notes he never held) weren't the only traumas inflicted on him. The priest had also chased him with his car. "And he had a gun," the accuser had testified in a deposition, "and he was threatening me and telling me over and over that he would hurt me, kill me, if I tried to tell anybody, that no one would believe me. He chased me through the cemetery and tried to corner me." Mr. Grover spoke also of the priest's stash of child pornography, an ever more prominent theme in the prosecution. * * * One of the defendant's early encounters

with the Grovers, a family with eight adopted children whom he met

in 1979, occurred when he drove past their house and was flagged

down. The youngest child, aged five, who had wandered into the pool,

lay near death from drowning while his mother and a nurse worked

in vain to bring him back. Fr. MacRae rushed in, picked the child

up, and got the water out of him so that his lungs functioned. More than halfway through the trial, as Thomas Grover's testimony began to pose ever more serious credibility problems, the prosecutors offered Fr. MacRae still another plea deal—an extraordinarily lenient one to two years for an admission of guilt. Relieved though his attorneys would have been if he'd taken it, they were unsurprised at his refusal. "I am not," he told one, "going to say I am guilty of crimes I never committed so that the Grovers and other extortionists can walk way [sic] with hundreds of thousands of dollars for their lies." The jury that the accused thought must acquit him, came in with a verdict of guilty within 90 minutes. Left entirely without funds and facing the three other trials yet to come, Fr. MacRae agreed to a post-conviction plea deal on all remaining charges—one to two years to be served concurrently with the sentence yet to be handed down in the Grover case. Scarcely a sentence at all. His defense lawyers, departing for other business, urged him to take the deal, which Fr. MacRae described, then and after, as a negotiated lie. Among the witnesses testifying at the sentencing hearing was Lawrence Carnevale, whose chronicle of claims of abuse had begun with a kiss. At least two church staff members recall that, back in the 1980s when all this was beginning, the youth told them that he had a hit list and that Fr. MacRae was at the very top—an announcement that came just after Fr. MacRae stopped accepting the young Carnevale's nonstop collect-calls to his new parish. Also testifying at the sentencing hearing was Mr. Carnevale's psychologist, Allen Stern, who opined that the chief cause of Mr. Carnevale's lifelong psychological problems were "the sexual events that took place with Fr. MacRae." Was his diagnosis Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome? Not quite, the psychologist explained, it was Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Delay. At sentencing, Judge Brennan charged that the priest had groomed and exploited vulnerable boys. He had assaulted Lawrence Carnevale, said the judge. "You destroyed Mr. Carnevale's dream of becoming a priest." The judge had harsh words too, for Fr. David Diebold, the only priest to come forward to speak in defense of Fr. MacRae. Above all he was incensed at Gordon MacRae's lack of remorse, "your aggressive denials of wrongdoing." "The evidence of your possession of child pornography," the judge declared, "is clear and convincing." Detective McLaughlin says, today, "There was never any evidence of child pornography." * * * Having given his reasons, the judge

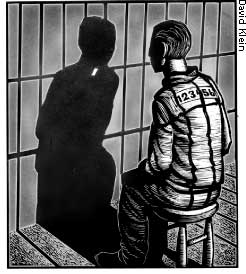

then sentenced the priest, now 42, to consecutive terms on the charges,

a sentence of 33-and-a-half to 67 years, [sic] Since no parole is

given to offenders who do not confess, it would be in effect a life

term. In the years since his conviction, nearly all accusers who had a part in conviction--along with some who did not—received settlements. Jay, the second of the Grover sons—who had, Detective McLaughlin's notes show, repeatedly insisted that the priest had done nothing amiss—came forward with his claim for settlement in the late '90s. And in 2004, the subject in the Spofford Hospital incident, Michael Rossi—"This is confession, right?"—came forward with his claim. "There will be others," predicts Fr. MacRae, whose second appeal of the conviction lies somewhere in the future. His tone is, as usual, vibrant, though shading to darkness when he thinks of the possibility of his expulsion from the priesthood—a reminder that there could be prospects ahead harder to bear than a life in prison. Ms. Rabinowitz is a member of the Journal's editorial board.

This concludes a two-part essay, the first

part of which was published yesterday. In the print edition, the subtitles of the two parts were: A Priest's Story These changes are significant, because they explicitly connect the MacRae essay, as its print version had not been connected, to Ms. Rabinowitz's recent book No Crueler Tyrannies: Accusation, False Witness, and Other Terrors of Our Times (New York: Wall Street Journal Books, published by Free Press, 2003). The Journal's posted version of the essay differs from the print version in other less important ways: the judge who sentenced MacRae in 1994 is called "the Hon. Arthur D. Brennan" in print, but just "Arthur D. Brennan" in the posted version; a few nonsubstantive words have been changed; Fr. has been changed to Father; and names, numbers, hyphens, and capitalization have occasionally been handled differently. Again, the version above reproduces the text of the print edition.] |

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.