Family Speaks Out on Alleged Abuse of Son

By Stephanie Salter

[Terre Haute IN] Tribune-Star

November 13, 2005

When Missi Limcaco's pastor told her the church would deal with the priest and youth minister who allegedly molested her son and other boys in the parish, she believed him. So did her boy.

“Finally, after months of avoiding it, Danny wanted to go to Mass again, so we did,” said Limcaco. “Guess who came down the aisle in the procession? I couldn't believe it. Danny just got up and went out of church. Afterward I asked the pastor how this could happen. He told me it was Easter season and they were busy and they needed Father Harry. He said he was sorry but he just hadn't thought about that.”

|

|||

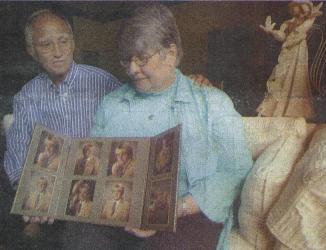

| Lost son: Oscar and Missi Limcaco are speaking publicly about the alleged sexual abuse of their late son, Danny, by a Catholic priest 25 years ago in hopes of sparing other children. "I'm tired of secrets," Missi says. Tribune-Star/Joseph C. Garza. At [right], Oscar Limcaco cherishes a plaque made by Danny as a child. Danny dies under suspicious circumstances in 1983. Below is a photo of Danny Limcaco at his confirmation in Texas. Photo courtesy of the Limcaco family. |

|

That was in 1981, a few months before the Rev. Harry E. Monroe would be removed from St. Patrick's parish in Terre Haute and placed on leave for a year by the archbishop of Indianapolis, the late Edward T. O'Meara. In 1983, Monroe would be assigned to his fifth post in less than 10 years, serving three parishes in the Tell City area.

A year later, the archdiocese would strip the priest of his official faculties because of more allegations of sexual misconduct.

Danny Limcaco would not be alive to learn of the dismissal or of previous molestation reports from Indianapolis families that had followed the young priest to St. Patrick's.

On March 10, 1983, Missi Limcaco found her 19-year-old son dead on the floor of a tool shed in the backyard of the family's home, then in Woodridge.

He had died from inhaling carbon monoxide from a running lawn mower.

Largely due to the family's inability to believe otherwise, Danny's death was ruled an accident.

“The [police] lieutenant was probably thinking, ‘suicide,' but I gave him a possible scenario: It was windy that day, the door might have blown shut. – I knew Danny had been depressed, but there was no note,” said Missi.

Only years later were Missi and her physician husband, Oscar, able to consider the other possibility.

There was no light on in the shed. Why would Danny have been running the mower in the dark? He knew the family rule about keeping the shed door open anytime the mower was worked on inside.

And, of course, the whole thing with Father Harry had never really been resolved.

“We'll never know for sure,” said Missi. “Do I think there's a connection between what happened with Father Harry and Danny's death? Yes, I believe there's a connection.”

Danny's younger half-brother, John, always believed there was a connection, and he said so until the day he died: Dec. 31, 1988. Suffering from early-onset bipolar disorder and drug abuse that therapists told the family had been triggered by Danny's death, John Patrick Limcaco shot himself to death after being involved in a minor traffic accident on North Third Street.

By the time that tragedy hit the family, Missi was well into her own psychiatric nightmare. Discovering the hard way that she, too, was genetically disposed to bipolar disorder, the mother of four was hospitalized a half-dozen times and spent much of her surviving two sons' early adolescence on heavy medication.

Through therapy, her faith in God and the support of her family and close friends, Missi has not required medication or hospitalization since 1991.

She realizes her history of mental illness will allow some people to discount the her family's story. She doesn't care.

The archdiocese already has admitted publicly that Monroe was ousted for allegations of sexual abuse back in an era in which that action was extremely rare. In addition, the Indianapolis diocese and Monroe, 57, who is now living and working in Nashville, Tenn., are defendants in four civil lawsuits brought by men who say the former priest sexually abused them as children at parishes in Marion County.

Missi herself has binders full of Monroe-related information that includes correspondence to and from archdiocesan officials. One of them in 2002 informed her that Monroe had been dismissed from the priesthood in 1984 and offered a deep apology “for the grave harm that was done to your son and to your entire family.”

The bottom line is, “I'm tired of secrets,” Missi said earlier this autumn, after joining advocates for abuse victims in a door-to-door information walk around St. Patrick's neighborhood.

“I'm not trying to be difficult, I just want Harry Monroe's name out there so no one else's children will become victims,” she said.

Opus Dei and perpetual adoration

These days, when a decades-old case like Monroe's becomes public, when other families like the Limcacos align themselves with the national organization, SNAP (Survivors of those Abused by Priests), assumptions often are made:

The family must hate the church; probably they are suing for big bucks; they want revenge for their children's pain; they can't let go of ancient history.

The Limcacos do not fit the profile. They are not suing. Their deceased boys are beyond therapeutic help, and their surviving sons do not need it. When they speak about Monroe, they theorize that he likely was abused sometime in his life.

|

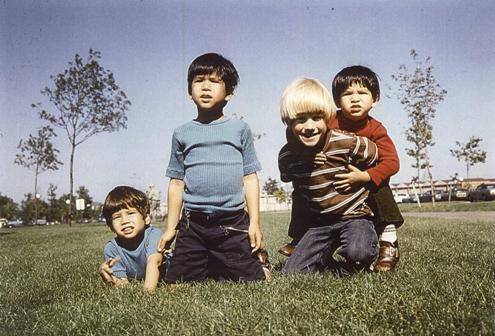

| At play: A family photo shows the Limcaco boys at play in Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy of the Limcaco family. |

Even Missi, who has stopped going to Mass, reserves her quiet anger for those above Monroe who enabled a much-accused child molester to allegedly collect more victims each time he was reassigned. While she thinks time in jail would be beneficial for the former priest, her overriding desire is to see the statute of limitations extended for reporting child sex abuse.

An adult convert, Missi was active for years at St. Pat's, long after the Monroe incidents and her sons' deaths. She sent the other two boys to school there and helped coordinate the parish's perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, an ongoing ritual in which the church remains open all day and night for worshippers to meditate and pray over a consecrated Communion host.

“I miss my community very much,” Missi said, “but I just can't listen to the homilies about love and compassion anymore. I can't listen to the hypocrisy. Sometimes I wonder what the priests and bishops think when they read the Gospel. Is it just words? Do you know what the Catechism says about sin?”

Quoting from the church's official teachings, she recited:

“Sin is a personal act. Moreover we have a responsibility for the sins committed by others when we cooperate in them – by not disclosing or not hindering them when we have an obligation to do so; by protecting evil-doers.”

Oscar Limcaco, a retired neurosurgeon, is even further from the stereotypical Catholic Church basher. Born and raised in the Philippines, he is a cradle Catholic who attends Mass regularly. He adopted Danny, Missi's son from a previous marriage, several years before the Church officially annulled that union.

“I will always be a Catholic, no matter what,” he said.

Oscar is also a longtime member of one of the institutional church's most loyal and conservative defenders, Opus Dei. He expects some of his fellow members not to understand why he has chosen to support his wife and speak publicly about what happened to his family.

“The purpose of this is not to destroy the church but to help improve it,” Oscar said. “Obviously, there is a serious problem in the church with pedophilia – Trying to address that problem should be viewed as a constructive effort.”

Many advances have been made by the Catholic hierarchy against the sex scandal crisis, for which the doctor said he is grateful. Much remains to be done, however, and, “excluding homosexuals [from seminaries, as the Vatican recently decreed] is not going to solve the problem,” he said.

As a physician, Oscar said he knows that “the first step to any treatment is recognizing and accepting that you have a problem,” something the church's leaders were too slow to do. Even today, many in authority still seem not to get it.

“I know about stonewalling and damage control,” he said. Using “legal maneuvers to protect yourself does not address the real problem.”

‘He was welcome in our home'

Father Harry Monroe was ordained in 1974 and came to St. Patrick's from Indianapolis in July 1979 at the start of the church administrative year. He assisted the pastor, the Rev. Joseph Wade, and served as the parish youth minister.

In his early 30s, Monroe had a motorcycle as well as a car and was known to give parish boys rides on the back of the bike. In a short time, he became a frequent visitor to the Limcaco house, sometimes for dinner, often just for a social call.

“He was welcome in our home. He would walk in and say ‘hi' then, ‘I'm going back to see the boys,'” said Missy. “He was like a big kid.”

Echoing the experiences of hundreds of families who have been scarred by sex abuse revelations in dioceses from Boston to Los Angeles, the Limcacos said they never imagined their children might be at risk. Monroe was a priest, a sacramentally ordained human representative of Christ on Earth.

|

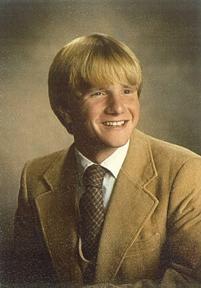

| School days: Danny Limcaco's Terre Haute North Vigo High School senior portrait. Photo courtesy of the Limcaco family. |

When Danny, then just 16, came home uncharacteristically sullen and withdrawn after a camping trip to Turkey Run State Park - only he and Father Harry had gone - Missi thought he was coming down with a bug.

“I asked him if he'd had a good time. He didn't answer me. I said, ‘Are you sick?' He turned away and said, ‘No, I'm just tired,''' she said.

Danny's smiles became fewer and further between. He avoided church and the youth group. Missi and Oscar thought he was going through adolescent ups and downs. More than a year would pass before Danny confided details to his mother about the camping trip and a previous outing with Monroe to Indianapolis.

In the hindsight of many years, the Limcacos realized that after the Turkey Run trip, Monroe had stopped coming around.

Not the only ones at St. Pat's

One day after Mass, Missi heard that molestation accusations about Monroe had surfaced regarding another parishioner's son. Missi came home and told Danny she thought she knew what had been bothering him.

“He broke down immediately and told me the whole thing,” she said. “When I asked him why he hadn't told us, he said he didn't think we'd believe him. He said, ‘I thought there was something wrong with me that caused him to do this.'''

Danny told his mother that Monroe had given him marijuana and liquor on both trips, insisting that parents would much prefer their kids learn about such things with a priest than their peers. At Turkey Run, Danny said, Monroe had insisted on zipping the boy's sleeping bag to his “to conserve body heat.”

Danny woke from an alcohol and drug stupor, he said, to find Monroe on top of him, groping him sexually. Terrified, he elbowed the man as hard as he could. He told his mother he was afraid that if he ran into the pitch-black woods he would smash into a tree, and he was afraid Monroe might hurt him. Lying on his stomach, he pretended to again pass out.

The day after Danny confided in her, Missi said, she was headed for the police station but first stopped by St. Patrick's to tell Father Wade. He talked her out of a police report, she said, and promised to notify the archbishop immediately, which he did.

Later that day, Wade called Missi to say the archdiocese was going to take care of the situation.

“He said there were six boys at St. Patrick's and that they and their parents were all supposed to write letters to the archbishop about what happened,” she said.

Wade, who resigned from the priesthood in 1996 for personal reasons, did not return a voice mail message from the Tribune-Star left at his home in the Indianapolis area.

A couple of weeks after Missi's conversation with Father Wade, a monsignor from the archdiocese phoned to say that “all the letters had been received,” Missi remembered.

“He was very nice until I asked him what they were going to do to protect the children. His tone totally changed. He was unbelievably intimidating. I can't remember his name, but what he said is burned into my brain. He said, ‘It is not your place to question the authority of the archbishop.”

A few weeks after that, Danny received a notecard in the mail, signed by O'Meara, thanking him “for your help” and praising the glory of the season. No mention was made of the alleged abuse.

“Danny threw it out,” said Missi.

|

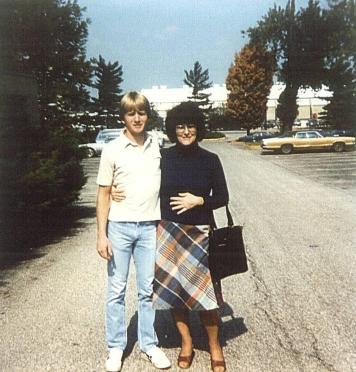

| On campus: Danny and Missi Limcaco stand on the campus of Indiana University. Photo courtesy of the Limcaco family. |

Off and on through the years, Missi tried to find out what happened to Monroe. Church officials had no information. A 1992 letter from an archdiocesan editor she had contacted expressed sympathy but no knowledge of the family's written complaints about Monroe.

“It's good, I think, that the cloak of secrecy has finally been lifted from this problem and the church is finally trying to do something about it,” the editor wrote.

It was not until a 1997 religious retreat, 14 years after Danny's death, that Missi learned that St. Patrick's had not been Monroe's last assignment.

Even then, Missi said, she kept going to Mass and worked to keep her relationship with the church separate from its painful mishandling of her son's ordeal. As more and more abuse cases surfaced in dioceses all over the country, she began to realize the size of the company in which her family found itself.

The turning point

In 2000, Missi read an Associated Press story in the Tribune-Star that touched a depth of rage she never suspected was in her.

An official in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nashville, Tenn., responded to lawsuits against a former priest - in prison for multiple counts of admitted child molestation - with a stunning announcement: If church officials were to be held responsible for knowing but not reporting the priest's crimes, then everyone else who knew about the abuse should also be held responsible - including 21 boys the priest admitted to molesting but who did not come forward to tell of the abuse.

All the years of guilt and remorse - not to mention grief - boiled up in her and fueled her anger at church officials. She educated herself about SNAP and followed the revelations of abuse and coverups in dioceses such as Boston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Dallas.

Time and again, she said, she waited for church officials to truly own their sins of the past, aggressively warn others about known abusers and join forces with victims to change the statute of limitations to extend the time in which an adult can report decades-old child abuse.

Instead, Missi said, most of what she has seen are empty apologies, buck-passing, priests and dioceses escaping criminal trials because legal reporting limits have expired, and an insensitivity to alleged victims that has inspired hundreds of them nationwide to sue for tens of millions of dollars in civil courts.

“The leaders of the church created their own nightmare,” Missi said. “What is so hard about getting a list of credible predators to the authorities? So, someone like Harry Monroe is no longer a priest? How do future employers in public schools, youth clubs, anywhere, know what they're getting into? How do they do a background check on somebody who was never reported?”

Last March, Missi finally reported Monroe's alleged abuse of Danny to law enforcement authorities.

“I knew no one could bring charges against him, but I thought that maybe the police had some kind of predators list,” she said. “The Terre Haute police were very nice to me but told me I would have to go to Rockville, because that was the jurisdiction for Turkey Run.”

The detective there was nice, too.

“He listened to me for a long time and took a lot of notes on a yellow legal pad. But I noticed there was never any form to sign. About two months later, he called me and said there was nothing they could do because it had happened so long ago. He said he hoped my coming in had brought me some closure,” said Missi.

“It didn't, but I'm not sorry I reported it. I just reported it 24 years too late.”

Stephanie Salter can be reached at (812) 231-4229 or stephanie.salter@tribstar.com.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How to get help

-- Information about SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, can be found at www.snapnetwork.org or by calling the Midwest office at (317) 833-9996.

-- Suzanne Yakimchick, the victim assistance coordinator of the Archdiocese of Indianapolis, can be reached at P.O. Box 1410, Indianapolis 46206-1410 or by calling (317) 236-7325 or 1-800-382-9836 ext. 7325. The archdiocese Web site is www.archindy.org.

-- Reports to Child Protective Services can be made on its hotline at 1-800-800-5556.

Two Web sites that provide information about sex abuse issues in the Catholic Church:

-- The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, www.usccb.org. Click on “Family & Laity Issues” then “Child & Youth Protection.”

-- An independent watchdog organization that collects and posts public documents and news stories about sex abuse issues in U.S. dioceses, www.bishop-accountability.org.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.