By Mark Johnson

Journal Sentinel Online

June 22, 2002

http://www2.jsonline.com:80/news/metro/jun02/53486.asp

Twin Lakes - Father Ron Kowalski stood before the congregation at St. John the Evangelist, facing his supporters and critics, and prefaced the terrible news: "Just when you think things couldn't get any worse . . ."

In the pews that first Sunday in June, Fred Silk held his breath. He had first attended the church in 1967, had watched his son and daughter receive the sacraments there and become altar assistants for the former priest, Father George Nuedling. He thought the world of Father Nuedling, who retired in 1993 after 25 years at St. John the Evangelist and died soon afterward. He admired Father Kowalski, too, and was sad that the church would be losing him soon.

But the year had been a series of dreadful revelations of abuse and misconduct in the Catholic Church, most recently the news that Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland had been accused of sexually abusing a 30-year-old man and had bought his silence in a $450,000 out-of-court settlement. As he listened to Father Kowalski, Silk could only wonder, What now?

|

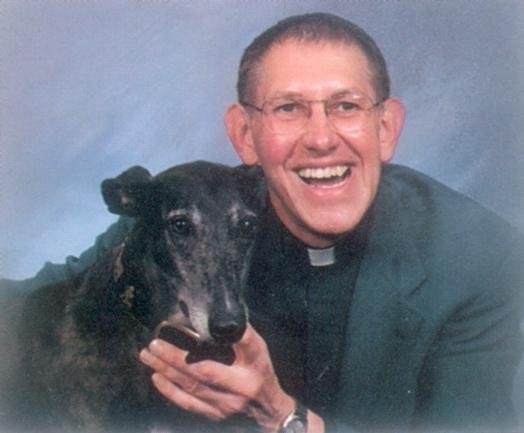

| Father Ron Kowalski replaced Father George Nuedling at St. John the Evangelist church in Twin Lakes. Nuedling, who died in 1994 after being with the parish for 25 years, was accused of sexual abuse. |

The news landed hard: Father Nuedling had been accused of sexual abuse.

Father Nuedling? The priest who was so pious and charismatic and popular with the children. The priest whose shadow Father Kowalski had toiled in these last six years. The priest some critics wanted him to be.

Suddenly, Silk felt winded, as if all the air had escaped from his lungs.

"It was total disbelief and amazement on everybody's face," he said later. "There was nothing we could say other than, 'I don't believe it.' "

There are some in this resort village of 5,100 people near the Illinois border who still don't believe it, even though a representative from the archdiocese has said that Father Nuedling admitted to some sexual misconduct and may have had 30 or more victims. So far, none of the victims has come forward publicly.

At St. John the Evangelist, a once close-knit congregation is now split between those who doubt the accusations against Father Nuedling and those who believe them. Between those who supported Father Kowalski and those who successfully lobbied the archdiocese to move him.

Last week a new priest, Father Michael Erwin from Shorewood, arrived at St. John the Evangelist to begin his first appointment as a full pastor.

"We pray for the new priest," said parishioner Carey Kuhlmey. "He's got a big order ahead of him for healing and rebuilding."

The painful fissures in this church may sound familiar to congregations across the country that have been torn apart by decades-old allegations of sexual abuse.

"If I could lift up a textbook case, that is it," said Donna Fiedler, an associate professor of social work at Catholic La Salle University, when told of the events at St. John the Evangelist. Especially common, she said, is the placing of a priest on a pedestal.

"I think Father Nuedling was put on a pretty high pedestal, maybe one that no one should be put on except Christ himself," said Doug Keen, a trustee of St. John the Evangelist.

In the last month, Father Nuedling's gravestone has been vandalized and the letters of his name have been removed from the Father George Nuedling community center at the church.

Powerful impression

The peaceful beauty of Twin Lakes, named for Lakes Mary and Elizabeth, has long made it an attractive summer escape, especially for visitors and retirees from neighboring Illinois. But in recent years, the full-time population has taken off, rising 28% in the last decade, from 3,989 in 1990 to 5,124 in 2000.

Meanwhile, St. John the Evangelist has experienced a steady decline in numbers - something that became an issue during Father Kowalski's tenure.

The church, which held its first Mass in 1942, was said to have served about 900 families at one time, although trustee Peter Pashos said that estimate is too high. At present, the church serves about 425 families. The congregation is predominantly older and of Polish descent.

When Father Nuedling arrived in June 1968, he made a powerful impression. The tall, balding priest with the slight mustache endeared himself to parishioners in numerous small ways. For example, Pashos remembers how his wife worried about flying as they prepared for a trip to Europe. Father Nuedling insisted that they see him before leaving so he could give them Communion.

Another time, an unknown baby had been found dead in the Fox River, Pashos recalled.

"Father Nuedling took that baby, got him a casket, got him clothes, got him a plot in the cemetery and got him buried. Now does that sound like a guy who's going to abuse a kid?" Pashos said.

Father Nuedling enjoyed golf. He smoked, a habit that worried his parishioners. He remembered the names of his flock. He seemed especially gifted at relating to the church's youth.

Brian Silk, one of his altar assistants, felt comfortable telling Father Nuedling about problems with friends and girlfriends and teenage growing pains.

"It was like talking to a good friend," he said. "He wouldn't say anything to anyone else. It was kept in confidence."

This was the side of Father Nuedling that everyone saw, said Jane Trussell, a former member of the church. Trussell, 45, said she encountered another side of the priest on an evening more than 30 years ago, when she saw him molest a boy on the church grounds. Another youth, she said, had to pull the priest off the boy.

"When I saw this happen with the one boy, we got out to the street and the boy turned to me and said, 'Don't you ever tell anybody what just happened. They won't believe you anyway,' " Trussell said.

There were other alleged victims of Father Nuedling, she said, and over the years they shared their experiences with each other. Some told no one else. Others tried to tell a parent, teacher or other adult. One boy told a few church members only to find himself shunned for it, Trussell said.

Whether anyone told police isn't clear. Police Chief Jeff Stoddard has been in the Twin Lakes department for 18 years and doesn't recall any abuse reports against Father Nuedling. But he couldn't say for sure whether a complaint was ever made.

Most of the families at St. John the Evangelist never had a clue that there was any controversy about their priest.

Meanwhile, his alleged victims grew into 30-, 40- and 50-year-old men who still break down and sob over what happened to them, Trussell said. Many left the Catholic Church.

"You're told to go to confession, but I never went again," she said. "I just felt why should I tell him my sins when he has done worse than anything I've ever done."

Father Nuedling said Mass for 25 years, even as a heart condition sapped all his strength. At one Mass he was too weak to stand and had to be held up at the pulpit. When it was announced that he was retiring, no one doubted poor health was to blame.

Father Nuedling retired in the summer of 1993 and died on Jan. 29, 1994. He was buried in the church cemetery in Randall Township.

New pastoral style

Father Nuedling was followed at St. John the Evangelist by Father Jerome Stoll, who had health problems and resigned after only two years. In January 1996, the archdiocese assigned a new priest to the church, Father Kowalski, a tall, bespectacled man with a lantern jaw.

Father Kowalski brought with him a new pastoral style and a host of changes decreed by Vatican II, everything from standing up instead of kneeling during portions of the Mass to the formation of numerous church committees. The changes did not sit well with some parishioners. Nor did Father Kowalski's personality.

"Father Ron was not only compared, but he was told at least 30 times a day that he was not doing it the way Father George (Nuedling) did it," said Pashos, the church trustee.

"I did feel sorry for him trying to follow an act like that," said parishioner Carey Kuhlmey, 48. "No one could have done a good enough job. But that isn't an issue now."

It isn't an issue, Kuhlmey said, because Father Kowalski did much on his own to alienate parishioners such as herself. She said he cut Masses, bristled at criticism and asked his opponents to leave St. John the Evangelist. He dissolved a Parish Council over disagreements and eventually fired her from the Cemetery Committee after the committee questioned how money was being invested.

It wasn't simply his direct manner, she said. "Direct we could have handled." She said the problem was the priest's inability to tolerate dissent.

Families left the church, though just how many is unclear.

Father Kowalski, 55, said he arrived at a church where change came very hard. He cut the number of Masses at the suggestion of an archdiocesan committee. He introduced and explained changes in the service that would bring St. John the Evangelist in line with Vatican II.

Most of all, he sought to make the church more than just "a filling station," where people came once a week to fill up on liturgy. He celebrated Mass at local nursing homes and encouraged parishioners to become more involved in the community at large.

Parishioners complained, and not just about the changes. Some disliked the sandals he wore. Father Kowalski received unsigned letters criticizing his haircut. He told those who seemed especially displeased with him that they had the option of worshipping at another church. There may have been one or two critics, he said, whom he actively encouraged to go elsewhere.

In retrospect, he said, he erred in appointing people with long histories at the church to an interim Parish Council. When they complained about him to the archdiocese, he dissolved the council and began forming a new one.

Despite the conflict, Father Kowalski asked the archdiocese for another six-year term at the church. He still had his supporters, including both trustees.

"Eighty percent of that parish was good," he said. "I think they were becoming a very loving, caring community."

The struggle between Father Kowalski and his critics ended this January, on the Feast of the Epiphany. Father Kowalski received a letter from the archbishop saying he would not be reappointed.He is taking a leave of absence before accepting his next assignment.

"We made a decision that was based on the information available to us," said Jerry Topczewski, a spokesman for the archdiocese. "And after consulting with parish leaders, we felt it was in the best interests of the parish and the best interests of Father Ron that he move to a different assignment and that someone else be assigned to be pastor of the parish."

Previous abuse

Father Kowalski's term was winding down when the news about Father Nuedling surfaced in late May.

Pashos, the trustee, was driving home from vacation when he got a call to head over to the church cemetery "right away." On Father Nuedling's gravestone someone had scrawled a message in black marker: "Pedophile, burn in hell."

A few days later, Father Kowalski was telling the congregation about the accusation and announcing a town meeting with the archdiocese to discuss the matter.

Maureen Gallagher, director of the Archdiocese Department of Parishes, came to St. John the Evangelist and told parishioners that Father Nuedling had admitted sexually abusing a boy at a previous church, St. Rita's, in West Allis. For some seven years after his admission, the archdiocese allowed him to continue as priest of St. John the Evangelist under the condition that he never be alone with minors.

Moreover, Father Nuedling had not retired. Gallagher said he had resigned from St. John the Evangelist after being confronted with a second accusation. In fact, Gallagher said the archdiocese had received credible information that there were 30 or more alleged victims of Father Nuedling.

"It's shocking. It's very hard to reconcile the two images of a pedophile and St. George," Kuhlmey said. She believed the accusations, but there were doubters. Even the two trustees differed.

Keen said that after the first report about Father Nuedling, "there was some denial going on" in the church. He said victims of the priest should be believed and the church should do all it can to reach out to them.

Pashos said he won't believe Father Nuedling molested children until victims come forward with proof.

"Someone picks up the phone. They make an accusation and they hang up. They don't give their name. They don't give their address . . . ," he said. "Stand up. Stand up. Don't hide."

Some believed there were good reasons why victims had not come forward and why they might not even now. Many still spend summers in Twin Lakes or have family in the village. And then there was the high regard parishioners expressed for Father Nuedling at the town meeting with the archdiocese.

Trussell, who said she saw Father Nuedling molest a boy 30 years ago, listened as others defended the priest.

"It was like one of the best-kept secrets in town," she said, "And what we couldn't tell 30 years ago, people still don't want to hear."

Fred Silk debated what to do after he learned the news about Father Nuedling. A few days later he forced himself to make a painful phone call.

"Brian," he told his son, "I hate to bring this to your attention, but I have to . . . "

Silk explained what they had learned about Father Nuedling and asked his 25-year-old son, Father Nuedling's former altar assistant, had he ever encountered anything, or seen anything?

"Absolutely not," he told his father.

"To tell you the truth it was one of the worst things I ever heard in my life," Brian Silk said later. "I spent at least a couple of days bordering on tears, trying to figure out what to think about this. I had always looked up to Father Nuedling my entire life."

Final Mass

Last Sunday, several hundred worshippers filled St. John the Evangelist to hear Father Kowalski deliver his final Mass.

"God our father, we rejoice in the faith that brought us together. . . . Help us live as one family," he prayed.

Thin shafts of sun filtered through skylights in the modern church and through two vertical stained-glass windows to the right and left of the pulpit. In a congregation of mostly seniors, a scattering of young girls stood out in their flowered dresses. On this Father's Day, young boys tugged at the arms of their dads.

As Father Kowalski looked out on his congregation for the last time, one of the readings, Matthew 9:36, seemed to capture the moment:

At the sight of the crowds Jesus' heart was moved with pity for them because they were troubled and abandoned, like sheep without a shepherd.

"I'm sure that I echo the sentiments of most Catholics," he said "not only in the church of the United States, but particularly in our own archdiocese, as we too feel troubled, abandoned and betrayed. . . .

"But we're not here because of any particular church leader. We're here because of our faith in Jesus Christ."

Father Kowalski said he had done many things well, and had probably done some things poorly.

"I have feet of clay," he said, "and they're big ones."

When he finished the homily, a small pocket of the congregation stood and clapped. Then another group rose. And another. Finally most of the room stood together.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.