By Walter V. Robinson

Boston Globe

November 24, 2002

n the four weeks since the end of his 76-day ordeal as a priest falsely accused of molesting a teenage boy, Monsignor Michael Smith Foster has reimmersed himself in his work as chief canon lawyer for the Archdiocese of Boston. His friends have never wavered. And on Friday, about 200 of his fellow priests applauded resoundingly when he spoke of the horror of being in church-imposed limbo for so long.

|

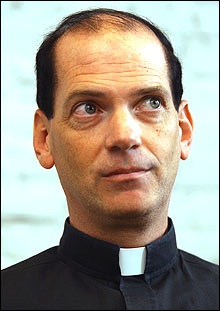

| Monsignor Michael Smith Foster Photo by David L. Ryan |

Foster case timeline

A chronology of the events involving the Rev. Michael Smith Foster:

August 14

Paul R. Edwards, 35, files a lawsuit in Suffolk Superior Court accusing Foster and the late Rev. William J. Cummings of molesting him while Edwards was at two Newton parishes in the early 1980s.

August 16

Edwards goes public with his charges in a televised statement. His lawyer, Eric J. Parker, admits that key dates given by Edwards are incorrect, but he declines to permit Edwards to be interviewed.

August 22

A Globe report raises doubts about the charges against Foster, noting that Edwards has a history of inventing stories and that friends of both priests and Edwards have offered statements that contradict Edwards's assertion that he was molested.

August 23

Parker says he has started an enormous effort to look at the truthfulness of his client's charges. More evidence emerges to challenge Edwards's account, and his credibility on other issues.

August 29

Parker, sending a signal that he has doubts about the charges, asks the court's permission to withdraw as Edwards's attorney. Judge Constance M. Sweeney, saying she has significant concerns about the credibility of the accusations, orders Edwards to appear in her courtroom on September 4.

September 3

Edwards withdraws his lawsuit with prejudice, meaning he cannot file it again, prompting legal observers to assert that the charges were probably false. Suffolk prosecutors announce a criminal inquiry into whether Edwards had indeed filed false charges. Foster expresses relief, but calls the church procedures for investigating complaints defective.

September 10

Cardinal Bernard F. Law tells Foster he has been cleared and reinstated, and asks Foster to celebrate Mass with him the following Sunday.

September 12

The Globe reports Foster's exoneration. The same day, Edwards meets for the first time with church investigators, and insists that his charges are true.

September 13

Late in the day, Foster issues a statement expressing joy at his reinstatement. But within an hour, he is asked to meet with church officials to discuss the renewed charges by Edwards. After a tense late-night meeting, Foster is placed on leave again and the investigation reopened.

October 30

Law calls Foster late in the evening to tell him that the second investigation has also concluded that the accusations were without substance. At 10 p.m., the archdiocese faxes a news release announcing his reinstatement.

December 27

Edwards reiterates his allegations against Foster and asks the archdiocese to reopen its investigation.

But so far, there has been no similar embrace from the leaders of the institution that Foster believes trampled on his rights - the archodiocesean officials who for more than two months seemed oblivious to evidence of his innocence and who decided on Oct. 30 to announce his reinstatement in a late-night fax that went almost unnoticed.

No one in authority, not Cardinal Bernard F. Law or any other bishop, has apologized to him for the way he was treated, Foster said in an interview last week. And, he said, it is an apology he deserves.

In an archdiocese still reeling from disclosures about the warm letters Law sent to serial pedophiles like defrocked priest John J. Geoghan, Foster's hopes for a meeting with the cardinal have gone unrealized - even though the two men concelebrated Mass last Sunday.

"Yes, I am angry at the treatment I have received from an institution I have committed my life to," Foster said. Without citing Law by name, he said, "I would wish that someone with institutional authority would sit down with me and talk to me about my experience, and the feelings that I've had, the emotional rollercoaster I've been on, the questions that remain."

He is puzzled, too, at what his friends believe are insufficient efforts by the church to fulfill its promise to help restore his reputation. "For the last 11 months, we have put a lot of resources into helping the cardinal with reputational issues. So this is not something new, restoring someone's reputation," he said.

Yet despite the focus on his case, Foster says he has no interest in being "the poster boy for the falsely accused." Foster says it is the victims of priests, and not him, who deserve the church's undivided attention.

"What I've been through doesn't compare to what these [victims] have been through. They need to hear how sorry the church is for what's been done. They need the apology. They need healing," he said. "They need to be reached out to. For people in authority, that's their first obligation."

Asked if the church is doing better in that regard, Foster responded: "On one day, yes. On another day, no."

Foster's interview with the Globe was cleared by the archdiocese.

Foster, 47, the first priest accused of sexual misconduct this year to be cleared, remains astonished by what happened to him: He, along with the late Rev. William J. Cummings, was accused in an Aug. 14 civil lawsuit of molesting a former Newton teenager, Paul R. Edwards, during the 1980s.

But within days, evidence surfaced that strongly rebutted the charges by Edwards, who has a history of fabricating stories. Edwards dropped the lawsuit after his lawyer abandoned the case. The judge assigned to the case expressed "significant concerns" about the truthfulness of the allegations. A week later, on Sept. 10, the archdiocese decided the charges were unsubstantiated and Law ordered Foster reinstated.

But three days later, the church reversed its decision, put Foster back on leave, and reopened its investigation after Edwards repeated the same charges in a meeting with church investigators. That decision, Foster said, "did not make sense to me. It still doesn't."

It was seven more weeks before the church once again determined that the charges were unsubstantiated. Foster very nearly gave up hope. There is, he said, "this wonderful, pious line that God doesn't give you more than you can handle. But I said, 'We've reached the end here. I can't handle one more thing. So You better take over."'

During those 11 weeks, Foster recalled, he lost nearly 20 pounds. And he suffered from tremors so severe he had to seek medical help to ensure he had not suffered a stroke.

When he first learned of Edwards's charges in mid-August, Foster said, "It was horrifying. ... It just struck to the core, that such a thing could be said. No one wants to be falsely accused of anything. But this particular crime? At this particular time? In our city? It was overwhelming."

So when he was summoned to meet with church investigators, he brought two civil lawyers and a canon lawyer with him, assuming, he said, that his denials would find an audience. Not so. The priests he met with, Foster said, had already determined that the charges were credible.

At that tense and confrontational meeting, he said, church officials refused even to provide him with a copy of the Edwards lawsuit. "There was a presumption of guilt," he said.

"You know, keeping in mind I went into the seminary at age 19, I am ordained at age 25, I've been a priest for 22 years with what I think has been a very fine service. And it just was absolutely overwhelming that I was being discarded and I hadn't even been asked anything," he said.

But with the help of the lawyers - and a substantial loan from a friend - Foster battled back. "I just was not going to surrender my priesthood to a lie," he said. "And that was my focus. And really, everything else became inconsequential."

Foster said that he was not alone in being mistreated by the archdiocese. There is also the case of Cummings, who died in 1994.

"I never heard that they investigated anything in regard to Father Cummings," Foster said. "And yet he has siblings. He has family members. His reputation was put on the line, and he couldn't defend himself. He's dead. I think the archdiocese has an obligation for all of its priests when an allegation is made, to look into it and make a determination."

If it is a puzzle to some why Foster would return to the archdiocese, it is a simple matter to him.

"If this was a job, then, yes, why would I stay? But it's not a job. It's my life. It's who I am," he said. "Why should I abandon the priesthood because the institution did this to me?" The priesthood, he said, is "where I think God wants me to be. That's what the vocation is all about. Why should I give that up because of a lie?"

The more appropriate analogy, he said, would be one's citizenship. "Let's say the government's done something to you that's terrible, not once but twice. Would you pick up and go to France, and no longer be an American? You'd say, damn it, I'm an American, I'm going to stay an American."

He paused, and with a smile, added, "Oh, I just said damn."

Foster readily answered questions about the investigation, and even about Law. But he said he would not answer any questions about Edwards, the now 35-year-old man who made the allegations. "I don't want to go down that road," he said.

But would he be willing to forgive his accuser, he was asked. "If someone asks for forgiveness, and they are truly sincere in asking for forgiveness, as a Christian, I would pray that I'd have the ability to forgive him," Foster said. "That's the best you're going to get from me."

The warm reception that Foster received on Friday came from members of the Boston Priests Forum, an organization of more than 200 of the estimated 950 diocesan priests who have been outspoken at times in their criticism of the archdiocese's handling of the sex abuse crisis. At the session, according to a priest who was there but who asked that he not be named, Foster spoke about how horrible his experience was and the helpfulness of prayer. He received sustained applause before and after he spoke, and a lot of priests expressed unhappiness with the way his reinstatement was handled.

Foster said he was eagerly looking forward to saying Mass for friends and supporters this morning at 11:30 at Sacred Heart Church in Newton. It is certain to be an emotional gathering, one where Foster will share something new with many in the pews: alienation from the church he loves.

His disaffection, he said, is something he hopes will make him a better priest. "The alienation of Catholics is real," he said. "I hope I can be even more empathetic to individuals who feel alienated from a church that they love. It's an awful feeling."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.