Editors Note: This Article Is Indebted to a Considerable Extent to Writings by Father Louis L. Renner, S.J.

Alaskan Shepherd

June-July 2003

No one knows exactly how long Hooper Bay has existed as a settlement. Some believe its founders migrated across the Bering Strait from what is now Siberia as long as six thousand years ago. In fact, some of the oldest archeological artifacts have been found near Cape Romazoff, a mere twenty miles from the present location of the village. It is known Central Yup’ik Eskimos have occupied that Hooper Bay village site for many generations.

|

The present-day Eskimo name for the village is Naparagamiut, meaning “the stake village people.” Just what “stakes” are referred to is not known. The name, “Hooper Bay,” came into common usage after a post office with the same name was established there in 1934.

|

| “What strikes me most about the people is their gentle demeanor when dealing with others and this comes from a people who

have for so long lived in such harsh conditions, certainly of winter climates, at times with scarcity of food, and in most recent

times, challenging of social and economic conditions.” --Father Gregg D. Wood, S.J. current pastor Little Flower Church, in Hooper Bay, Alaska. |

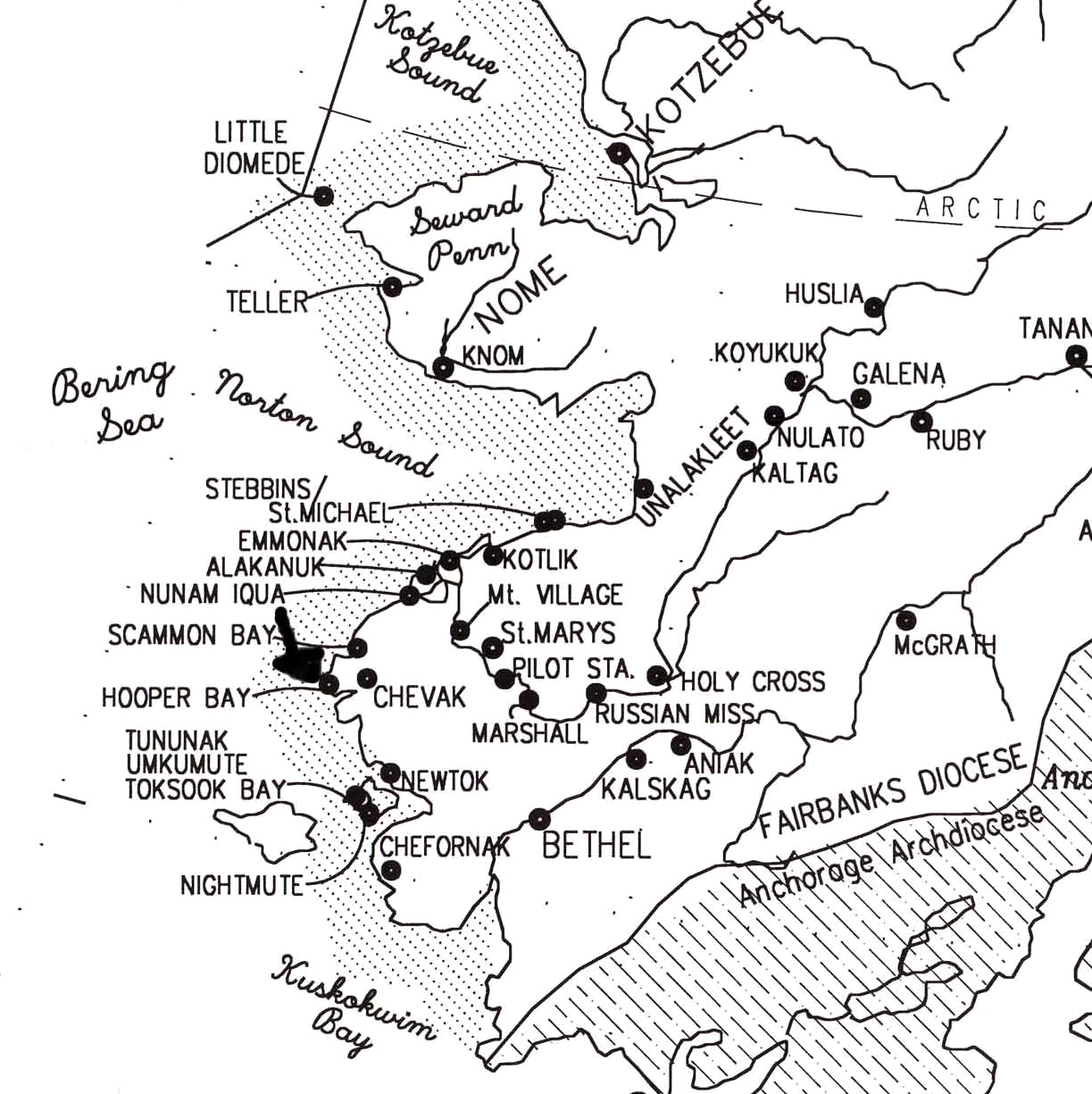

The village of Hooper Bay, with a population of 1,014, is located on Hooper Bay, on the Bering Sea coast of western Alaska, approximately 25 miles south of Scammon Bay, in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. The village separates into two sections. The old, heavily built-up section sits on two gently rolling hills. It was originally located a little closer to the life supporting Bering Sea. There, Eskimos lived in sod houses, which were partially underground in order to retain heat. Old Hooper Bay continued to be inhabited into the early 1940’s. The Eskimo name for the older part of the village was Askinuk—which refers to the mountainous area between Hooper Bay and Scammon Bay. The newer section is situated on flat, sandy land surrounded by the Clarence Rhode National Wildlife Range, a marshy tundra dotted with numerous ponds and the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

|

Hooper Bay was first visited by Catholic missionaries beginning around 1890. The U.S. government, early in the 1900s, opened a school there staffed by Lutheran (Swedish Covenant) teachers. They allegedly used their position to spread their religion—much to the dismay of the Jesuit missionaries. For many years, therefore, the Jesuit missionaries urged that a Catholic mission, with a school, be established in Hooper Bay. The mission was finally established, in 1928. Father John P. Fox, S.J., has left details concerning its establishment. Father Anthony M. Keyes, S.J., and Brother John Hess, S.J., along with a group of “big boys,” came down from Holy Cross Mission on the mission boat, the Little Flower, which was loaded with building materials. Brother Aloysius B. Laird, S.J., operated the boat. When the building was about three fourths finished, Jimmy Droane— one of the “big boys” from Holy Cross— was left behind to finish it. Soon thereafter, in September, 1928, Father Francis M. Menager, S.J., took charge of the new mission, named “Little Flower Mission.” The dream of having a Catholic school in Hooper Bay remained just that—except for the three years, when the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows conducted a kind of school there.

No name is more closely associated with the Hooper Bay mission than that of Father Fox. He served there from 1931-46, longer than any other priest before or after. In many respects, he is the one who set the tone of the mission. In 1932, he founded the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows, who had their motherhouse in Hooper Bay. He built a convent for them there in 1938. He was Hooper Bay’s first postmaster. He was the radio operator in Hooper Bay. He saw a reindeer herd given to the Hooper Bay mission, in 1933, “as trust property to manage for the people’s benefits.” In general, he strove to improve the lives of the Hooper Bay people, and he did so with notable success. As a captain in the Alaska Territorial Guard, he was head of the Hooper Bay company during World War II.

Father Segundo Llorente, S.J., who knew Father Fox well, had chosen him as his spiritual director, because he was “the only pious guy in the neighborhood.” Father Llorente recalls being summoned for help by Father Fox and relates this story about the rough trip from Alakanuk to Hooper Bay— “The first day we covered only fourteen miles to Pastolik, where we slept. The second day we reached Uksukalik. The third day we were fortunate to make Kapothlik. The fourth day we made it to Scammon Bay. By now I was very well battered. The poor dogs were not pulling and snow was fresh and deep. We had to walk alongside and give the dogs a hand. One of them lay down totally exhausted, so we let him loose and we never saw him again. I was walking mechanically, almost unconscious of what I was doing. I told the Lord that every step I took had to count for one sinner who needed conversion. When the step was not too deep, I figured that a light-weight sinner had been saved. When my foot sank to the knee, then I knew that some real heavy-weight criminal had been brought back to the fold. I was amazed at the large number of sinners walking this earth.”

Throughout its history, Little Flower Mission in Hooper Bay virtually always had a resident priest—though generally he was responsible also for outlying stations, and so was away for from time to time. Some years, two priests were stationed there. The principal pastors of the Hooper Bay parish have been Jesuit Fathers: Menager, 1928-30; Fox, 1931-46; Paul C. O’Connor (who found Hooper Bay “a mud-hole during the summer and a wind-swept tundra during the winter,” and who, as a member of the Alaska Housing Authority, brought new housing to Hooper Bay),1946-53; Henry G. Hargreaves (who found the people of Hooper Bay “most affable”), 1953- 57; Norman E. Donohue, 1957-64; George S. Endal, 1964-68; James R. Laudwein, 1968-69; James E. Jacobson, 1969-76; Bernard F. McMeel (who oversaw the building of the new church in 1977), 1976-77; Daniel J. Tainter, 1977-79; and Richard L. McCaffrey, 1979-81. Father John A. Hinsvark, priest of the Diocese of Fairbanks, followed him 1981-90. Jesuit priests from St. Mary’s Mission, Andreafsky, visited Hooper Bay during the year 1990-91. Jesuit Fathers Mark A. Hoelsken was at Hooper Bay, 1991-96; and Gregg D. Wood, 1996-2003.

Eskimo Deacons, too, have served and are serving their Hooper Bay parish: Joseph Lake (deceased) and James Gump. Hooper Bay saw also the services of different Sisters. Foremost among them were the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows, 1932-45. On August 5—Feast of Our Lady of the Snows—1932, the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows was officially founded at Hooper Bay. The charter members of the community were, not surprisingly, two of Father Fox’s catechists at the time: Annie Sipary and Clotilda Leo. Other candidates, schooled at St. Mary’s Mission, Akulurak, and at Holy Cross Mission, soon joined the two.

ST. THERESE NOVENA

|

To the friends and benefactors of the Missionary Diocese of Fairbanks: In September we begin our annual Novena to the Pa- troness of the missions of Alaska, St. Therese, “The Little Flower.” The Novena will begin on September 23 and will end on the Feast of St. Therese, October 1. On each of these days a Mass will be offered for our friends and for their needs and petitions.

You are invited to submit petitions to be remembered during the novena. No offering is necessary. Any re- ceived will be used to support our ministries here in Northern Alaska.

You are also invited to join us on the novena days (Sep- tember 23-October 1), by praying the following prayer: “O Lord, who said, unless you become as little chil- dren you shall not enter the Kingdom of Heaven, GRANT US, WE BESEECH YOU, to so follow in the way of Blessed Therese in humility and simplicity that through her intercession these petitions and those of all our members may be granted as part of the shower of roses she promised to send upon this earth.” All petitions will be read and remembered in the Masses offered during these nine days.

Please detach and send intention portion. Use prayer above for the Novena.

TO: CATHOLIC BISHOP OF NORTHERN ALASKA

1312 Peger Road * Fairbanks, AK * 99709-5199

Please remember the following petitions during the Novena to St. Therese:

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Name______________________________Street___________________________________

City________________________________State_______________Zip_________________

The rules of the Congregation were of the kind common to Religious communities dedicated to an active ministry. Some f the rules and practices were taken from the spirit of Jesuit ules and practices and adapted to the circumstances of time nd place. Candidates had a two-year novitiate under the piritual direction and guidance of Father Fox. Daily there were piritual talks and spiritual reading, and there were annual week-long retreats in total silence. After completing the two- ear novitiate satisfactorily, candidates took their vow, but for nly one year. Any Sister that, at the end of that year, did not eel herself called to renewing her vows became automatically ree to go on in life as she pleased.

|

Father Fox soon had the Congregation off to a solid start, nd the Sisters were well received in the villages they served. But, a number of his fellow Jesuit missionaries serving in that eneral district had misgivings about the whole venture. Some

felt he could spend his time as a missionary more profitably. They felt that, given the prevalence of tuberculosis at the time and the early deaths so often resulting from it, he was “building on sand,” that he was wasting his time in preparing young women to be Sisters who might soon be dead. His answer to this objection: “Even if the Sisters die early in life, what of it? If the few years they lived, they lived working for their own sanctification and that of their fellow Alaskans, wasn’t it worthwhile?” Others thought the whole venture too expensive. And some wondered whether young Native women could be faithful to their vow of chastity, while living and working in a culture, which, up to that time, knew only married life as the norm for all. Some of the Sisters did die young, some left the Congregation on their own accord, and some were advised to leave, to get married, and serve as married catechists. The summary records of the Congregation show that, in the end, “the majority of the Sisters were good and loyal. There was not one single scandal.”

|

Those who thought the whole venture too expensive did not know that Father Fox—through his correspondence and newsletters to family, friends, and benefactors—was, in reality, able to take care of all his financial needs. He pointed out that the Sisters were also, to some extent, self-supporting, inasmuch as “they hunted rabbits and ptarmigan for the pot and gathered willows for the stove.” They helped support themselves, too, by gardening, fishing, gathering eggs and greens in season, and, in general, leading the traditional subsistence way of life. As the Congregation grew, more space was needed. By 1938, Father Fox was able to provide a two-story convent, with a full basement, for the Sisters. He tried to visit, as often as possible the Sisters in their outlying villages, but—given his many responsibilities—he was able to do this only at relatively infrequent intervals. Accordingly, it was his policy not to leave Sisters—although they were generally in pairs, or, if a Sister was alone, she had a lay woman companion—too long alone in a given village. He had them return to Hooper Bay for community life, Mass and the Sacraments, daily spiritual exercises and priestly instructions. This policy, too, accounted, in part, for the need of more space at Hooper Bay for the Sisters. As the years went by, it began to seem more and more odd to some that a priest continued to be in charge of the Sisters. It was arranged, therefore, that Ursuline Sisters, Mother Mary of the Blessed Sacrament and Mother Scholastica Lohagen, should come from Akulurak to Hooper Bay to serve as trainers and spiritual leaders of the Native Sisters. The two were at Hooper Bay from October, 1942, to August, 1945.

|

While Father Fox “felt that everything was taking on rosy colors,” some of his fellow Jesuits continued to have reservations about “this whole Sisters business”—and they were giving voice to their reservations. They were, he recalled, “talking without having seen for themselves. It was all hearsay. I was shouting at the top of my lungs to have them come and see, but nobody would come.”

On February 24, 1939, Walter J. Fitzgerald, S.J, was consecrated coadjutor to Bishop Crimont. Shortly thereafter, he made the rounds of the missions in northern Alaska. On June 12, 1942, he wrote to Father Fox, “The work of the Native Sisters in instructing the little ones in their prayers and catechism is excellent.” Bishop Crimont died on May 20, 1945, “and with him,” according to Father Fox, “we lost our best friend.” Bishop Fitzgerald was now the man in charge. By 1945, he, seemingly, had forgotten what he had observed three years earlier at Hooper Bay. And—after having listened for some years to what fellow Jesuit missionaries in that part of Alaska were saying about the Native Sisterhood—he came to the conclusion that it was “premature,” that it was “a liability, rather than an asset.” Almost immediately after replacing Bishop Crimont as Vicar Apostolic of Alaska, he “suspended”—in reality, suppressed— the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows, and dispensed the Sisters from their vows.

|

August, 1945, was a black month for the Native Sisters and Father Fox. On the fourth, he wrote in the Hooper Bay house diary: “Mail arrives. With it an order from Bishop Fitzgerald dispersing (the document says ‘suspending’) the Native Sisters. The natives, as well as the whites, deeply regret the Bishop’s decree killing the community. Fiat!” The following day, Father Fox read the decree of suppression to the assembled Sisters. The wording of the decree is rather informal, oblique, and comes at the beginning of what, to all appearances, is a routine letter. The letter, dated Juneau, Alaska, August 5, 1945, begins with a greeting and two key sentences: “Dear Father Fox, Today, the feast day of Our Lady ad Nives [of the Snows], you and the former Sisters of the Snow have been in my prayers that you may sustain the blow of dissolution of the pious association to which you have been so devoted. I trust that it was the guidance of the Holy Spirit that directed the action, and I add my sincere wishes that you and all will take it as coming from the Will of God.”

On August 7, from Hooper Bay, Father Fox wrote to Bishop Fitzgerald: “My dear Bishop: I wish you could have read your document to them yourself. As it was up to me, I read it to seven weeping women. You have no idea of the consternation it caused, even though we all expected this ever since your visit last winter.” And then, as if to exonerate to some degree the bishop for the action he had taken, he adds, “However, as in most of this affair, you have been following the lights of others.” The “others” are, of course, their fellow Jesuit Alaskan missionaries.

The ex-Sisters, lay women now, returned to secular life. The two Ursuline Sisters returned to Akulurak.

“To me personally,” said Father Fox in his later years, “it [the suppression] was a big blow.” Even in his old age, he considered Bishop Fitzgerald’s decision to have been a wrong one. But, being the obedient man that he was, he had reconciled himself to it as God’s will, and, at the time of the suppression, wrote and said little about it, for “the subject was dynamite.” Jesuit historian, Father Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., wrote, “When these Sisters were gone, there was a kind of emptiness in the Alaskan Church, and no one felt it more keenly than Father John Fox.”

During the 13 years the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows was in existence, a total of 22 candidates were admitted to it. Of these, five died a holy death as Sisters. Eight left of their own accord. Two of these had pronounced temporary vows and had served the missions well for about six years. The other six left as novices. One had been sent away by Bishop Fitzgerald to take care of her mother. One was advised to go to help her family. One was told to leave. Six were still members of the community, when the Congregation was suppressed. According to Father Fox, “No one ever left the community with hard feelings!”

|

During the years 1942-45, Ursuline Sisters Mother Mary of the Blessed Sacrament Hardegon and Mother Scholastica Lohagen were at Hooper Bay to help with the formation of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows. During the early 1980s, Sister Mary Schrader, C.S.J., served the Hooper Bay parish. From 1989-94, Sister Julie Marie Thorpe, S.N.D. de N., and Sister Angela Fortier, C.S.J., did likewise.

Buried at Hooper Bay are Deacon Joseph Lake, and Father John B. Sifton, S.J.—who also died rather unexpectedly, at Hooper Bay, on October 20, 1940. Buried with them are two Sisters of Our Lady of the Snows: Clotilda Leo Chakatar and Mary John Baptist.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.