By Melissa Evans

Santa Barbara News-Press [California]

February 26, 2006

http://www.newspress.com/Top/Article/article.jsp?

Section=LOCAL&ID=564688552693203095&ARCHIVES=true

The cross that fell from the building where Roman Catholic priest Mario Cimmarrusti once lived sits among the sparse remnants of St. Anthony's Seminary: old trophies, yearbooks, a wood desk with names etched underneath. These and other artifacts were tucked in a storage trailer on the lawn outside the Santa Barbara Mission when the Franciscan Friars sold the 19th century stone seminary last June.

The emotional memories, particularly for boys who went to the school in the late 1960s, are harder to catalog. Even harder to tuck away.

They will re-emerge in an Oakland courtroom March 6 when a lawsuit filed by one of those students, known only as John Doe 39, is expected to go to trial. He sued the priest's religious order, the Franciscans, over alleged sexual abuse in the late 1960s. Eight similar lawsuits involving the Rev. Cimmarrusti, who was the focal figure of campus life during his time at the all-boys high school, are also pending in Southern California.

|

|

|

|

John Doe 39 filed his lawsuit in the Bay Area where the Franciscan order is based. The others will go to court in Los Angeles when hearings are scheduled.

Though the Rev. Cimmarrusti isn't named as a defendant in any of the cases, there is little doubt that he caused immense pain in Santa Barbara.

He was among 11 priests found to have molested boys at the seminary from 1964 to 1987, accounts of which are included in a report the Franciscans commissioned in 1993 after several former students came forward. Franciscan leaders had already removed him from ministry a year before. Lawyers say the upcoming trial, like the other lawsuits, will focus more on who knew what, when, and whether leaders should have removed him from the ministry sooner.

The trial will flash back to the six years that the Rev. Cimmarrusti was at St. Anthony's Seminary, from 1964 to 1970. Former students will recall their encounters with the bespectacled priest who taught them Spanish and religion, and who was in charge of discipline, assisted with the choir and ran the school medical clinic.

"He was the most visible person on campus," said Paul Fericano, who says he received a settlement in 1996 from the Franciscans because of alleged sexual abuse by the Rev. Cimmarrusti. "He was everywhere."

Mr. Fericano is not among the nine current litigants. He has undergone counseling; he has no grudge against the order. Mr. Fericano applauds the friars for facing the problem long before the nationwide scandal broke in 2002, and has tried to help them and victims deal with the aftermath.

Mr. Fericano has been criticized, particularly because he routinely speaks on behalf of the Franciscans and advises victims to reconcile. He pushed the friars to save some of the artifacts from St. Anthony's when the building sold in hopes of creating a museum or archive, partly to remember the good times there.

Other alleged victims of the Rev. Cimmarrusti talk frequently to the media, angry with accusations that the friars knew what was happening and did nothing. And some quietly file lawsuits under anonymity, never even telling relatives what happened.

John Doe 39, a 54-year-old Washington state resident who came to St. Anthony's as a sophomore in 1966, claims the Rev. Cimmarrusti fondled him during medical exams, masturbated him and showed him pornography, among other more serious acts of sexual misconduct, according to documents, and interviews with his lawyers. The physical and sexual abuse was so bad that he ran away and sneaked onto a plane at Los Angeles International Airport, according to court papers. He says in his lawsuit that he told at least two administrators about what was happening -- a claim that will be contested in court.

The Franciscans, he alleges, were negligent in their duty to protect him from a known sexual predator, and that he has suffered severe emotional distress as a result.

ELDERLY, AILING PRIEST

The Rev. Cimmarrusti, now 76, could not be reached for comment. His lawyer, Skip Howie of San Mateo, said his client has been instructed not to talk to the press as the trial nears. The priest, who lives at a retreat house in Danville, has said in the past that he did not do anything a doctor wouldn't do and that he doesn't remember abusing boys.

Brian Brosnahan, general counsel for the Franciscans, would not discuss whether the alleged abuse itself will be contested in court, but acknowledged that the Franciscans permanently removed the Rev. Cimmarrusti from ministry during an independent board's investigation of sexual abuse at St. Anthony's. Several people involved in the process confirmed that he was one of the 11 unnamed priests found to have abused boys at the school.

The Franciscans say he is being monitored closely, that his health is failing, and that he has no contact with children or the public at large. It is unclear whether he will be called to testify at the upcoming jury trial, lawyers on both sides say.

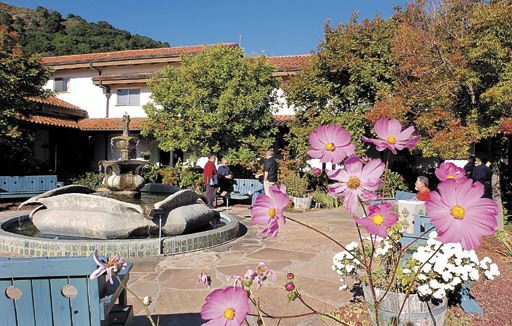

The upscale San Damiano Retreat House where he lives is situated in the hills overlooking San Francisco's East Bay region. Its tree-studded trails, ornate fountains and peaceful setting play host to a wide array of religious and community groups throughout the year.

A native of Inglewood, the Rev. Cimmarrusti was ordained in 1957 after graduating from St. Anthony's and the Franciscan Theological Seminary, now located in Berkeley. He was 34 when he joined the two other priests at St. Anthony's.

Former students say they immediately feared the priest, a rotund man nicknamed "the ogre" because he was in charge of discipline. He is pictured in a 1967 school yearbook with his mouth ajar and his hand thrust in the air, seemingly in anger.

"His philosophy is that someone has to be the ogre," students wrote in a dedication to the Rev. Cimmarrusti that year. "Father takes his responsibility of prefect of discipline quite seriously. In these days of change and wondering which way to go, father does his best to keep down the chaos and to build up the community."

"BOOT CAMP SERGEANT"

Bob Millick remembers his first encounter with the priest when he arrived on campus in the fall of 1966. The Rev. Cimmarrusti grabbed a newspaper and Reader's Digest that he had brought and threw them into the trash, he recalls.

"It was like going through customs and immigration for hell," said Mr. Millick, who has an active civil lawsuit against the Franciscan order and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in Southern California alleging abuse by the Rev. Cimmarrusti.

"He played the role of the classic boot camp sergeant."

The students had all left their homes to live at St. Anthony's full time to study for the priesthood. In the Catholic tradition, priests are seen as God's representatives on Earth, and they are treated as such in church life.

Expulsion from the seminary, or bad reports to pastors and parents back home, "spelled social disaster to kids our age," said Mr. Millick, who lives in Windsor.

Former seminarians say it was a particular honor to train with the Franciscans, a religious order that had mythical appeal for Bruce Thurston, a Hayward resident who entered in 1964 but was not sexually abused. "I was enchanted by the Franciscans," he said. "(St. Anthony's) was a very special place to be."

The seminary was housed in an intimidating edifice constructed in 1899 with winding staircases, cobblestone walkways and musty hiding places. Its vaulting towers peek from behind the Santa Barbara Mission, which is also run by the Franciscans, an order known for simplicity and humility.

Although the Rev. Xavier Harris was rector of the school at the time, no one was more physically present than the Rev. Cimmarrusti, former students say. He led the meals from his seat on an elevated stage overlooking all the boys. He chaperoned field trips to Hendry's Beach and directed school plays. He doled out medicine when they got sick and spankings when they misbehaved.

BEATINGS, "HERNIA CHECKS"

Ron Bottorff says he received a settlement from the Franciscans in the 1990s because of one beating by the Rev. Cimmarrusti after speaking when he was not supposed to.

"He made me strip naked, lay across his lap and he spanked me 33 times -- once for each year of the Lord's life," said Mr. Bottorff, a Palm Springs resident who is not involved in the current litigation. "I was begging him to stop."

The boys were forced to lay across the priest's bare lap in view of his erection, according to the lawsuits and accounts by students. Their faces were then pressed into his groin while he prayed for them, according to court papers.

Former students say they routinely heard screams coming from the Rev. Cimmarrusti's room and could see the black and blue marks on their classmates. Many, including Mr. Millick and Mr. Bottorff, can't imagine how the other school leaders didn't know what was happening.

"It is true that one had to keep the blinders on and not look at obvious signs that something was wrong," Mr. Millick said.

As head of the school infirmary, the Rev. Cimmarrusti would often call the boys back to his room after beating them to apply lotion as an excuse to fondle their genitals, according to a lawsuit filed by Nye, Peabody & Sterling, a Santa Barbara law firm representing several of the Rev. Cimmarrusti's alleged victims.

Many of the former students also say they were molested during "hernia checks," which the Rev. Cimmarrusti performed several times a month, according to the lawsuits. Two say they were required to go to the priest's room for weigh-ins and to check their thyroid glands because they were overweight. In court papers, another said he was molested after being treated for athlete's foot because the priest wanted to make sure it hadn't spread to his genitals.

Mr. Bottorff says he was among a group of freshmen forced to walk across campus in their underwear after the Rev. Cimmarrusti caught them cheating. They were herded into a classroom, barely clothed, and re-took a test under his supervision.

"Everybody saw us," Mr. Bottorff said. "They were all making fun of us."

Many of the alleged victims say the Rev. Cimmarrusti favored the freshmen, possibly because they were smaller, less confident and more vulnerable.

He also had more access to them.

Freshmen slept upstairs in an open dormitory nicknamed "The Barn" because it had no separate rooms. The Rev. Cimmarrusti's room was away from the main friary, directly downstairs from the freshmen.

On a recent tour of the seminary, Mr. Fericano paused in front of a limestone building that housed the freshmen study hall.

"Painful memories there," he said.

SEX EDUCATION

After dinner each night, freshmen would spend a few hours in silent study. Sometimes a messenger would come and hand one of the boys a note -- the Rev. Cimmarrusti wanted to see him. The boys didn't talk about it, but they knew molestation was in store, Mr. Fericano said.

"When they came back, they would tap the desk of the next boy," he and others recall.

Former students spoke of the fear they felt when hearing the priest's long rosary beads clink together on the side of his brown habit. They could always hear him coming.

"That sound was like a nightmare," Mr. Thurston said.

In addition to his duties as an administrator, the Rev. Cimmarrusti taught the sophomore course on church doctrine, which included sex education. He would often put students down in class by poking fun at medical conditions or learning disabilities, former students said.

He was excessively rough when he wrestled with the boys at athletic practice or on the beach, Mr. Thurston said. On one trip to Hendry's, Mr. Thurston said he became jealous because the Rev. Cimmarrusti was paying attention to four boys in particular while wrestling with them in the sand.

"I tried to get involved, and I grabbed his robe," he recalls. "He turned around and slugged me with a clenched fist as hard as he could."

Dejected and embarrassed, Mr. Thurston said he walked back to the seminary, and later mustered the courage to apologize.

YEARBOOK SMILES

The priest's hard disposition, however, is not evident in many of the old pictures from St. Anthony's. He is seen smiling with the choir, rough-housing with students and refereeing sporting events. He was famous for growing daffodils.

In their dedication, the students wrote that, "When among (the daffodils) he is no longer an ogre but a man working in the mud. To hunt snails with him is to realize that he has discovered at least a few of the many secrets of life."

He and the other friars used to stage a skit and concert for parents of students at the end of each school year. The Rev. Cimmarrusti was also an integral part of the community Los Posadas and Old Spanish Days celebrations.

"He had a smile that was just unbelievable," said Dyane Munana, a longtime community member who acted as a surrogate mother for many of the homesick seminarians. "Everybody thought he was terrific."

Now, like many other community members who were connected with the school and parish, she is sickened by what allegedly happened behind those stone walls. Ms. Munana is among a small group of parents and former parishioners who still meet regularly to console each other and push the Franciscans for more disclosure.

The former students said they never talked about what went on -- it was considered a part of normal life. Mr. Millick and Mr. Bottorff stayed in touch after they left the seminary, and only later exchanged their stories of alleged abuse.

Around the same time, in the late 1980s, tensions at St. Anthony's were boiling. A handful of former students and their parents were pressuring the friars to look into sexual abuse by two other seminary priests, Robert Van Handel and Philip Wolfe -- both of whom eventually served jail time.

When Mr. Bottorff and others came forward with their stories about the Rev. Cimmarrusti, the Franciscans assembled a team that included an attorney, two counselors, a priest and the father of one alleged victim, who were asked to look into the claims. (The alleged sexual abuse victims who are suing the Franciscans say leaders knew what was happening long before this investigation began.)

"HEAL THE PAST"

After mailing roughly 900 letters to former students, the team identified 34 boys who had been abused by 11 priests between 1964 and 1987, when the seminary closed for financial reasons. The former provincial of the St. Barbara Province of the Franciscan Order, which stretches from Washington to New Mexico, went on national television to apologize.

"We publicly and firmly want to take personal and corporate responsibility for systemic changes to heal the past, address the present and plan for the future," the Rev. Joseph Chinnici said in 1992.

The order compensated some of the victims an unknown amount of money and offered them counseling. The friars, with help from the team, set up procedures to deal with new complaints and established guidelines on acceptable behavior.

Because of the statute of limitations, Mr. Van Handel and Mr. Wolfe were the only priests convicted of criminal charges. Mr. Wolfe later committed suicide, and Mr. Van Handel lives as a registered sex offender in the wooded hills of Santa Cruz. He is no longer a Franciscan.

After all of this pain, the friars thought healing could begin.

The wounds of St. Anthony's, however, would reopen in 2002, when The Boston Globe sparked a nationwide firestorm over priest sex abuse after publishing several accounts of Catholic leaders' failure to investigate. The scandal quickly made its way into newspapers across the country.

But little could be done in the courts, either as criminal or civil cases, because most of the alleged abuse happened decades ago. California lawmakers then took unprecedented action to help hundreds of victims who were coming forward by lifting the statute of limitations on civil cases for one year in 2003 (the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a law allowing old cases to be tried criminally).

Mr. Millick, one of the original 34 boys identified by the Franciscans, decided to file a new lawsuit. Due in part to media attention, a fresh wave of alleged victims, including John Doe 39, also came forward. Lawyers say they have identified more than 60 victims of sexual abuse allegedly committed by priests throughout Santa Barbara County.

Most of their cases were bundled together with 500 other lawsuits against roughly 220 priests within the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which oversees Catholic parishes, schools and religious orders in Santa Barbara. The case headed for trial next month is unique because it was filed only against the Franciscan Order in Northern California, where litigation is moving along more swiftly.

If the case is not settled out of court before March 6, more information about what happened in the late 1960s will likely become public. Depositions of friars, many of whom still live and serve at the Santa Barbara Mission, could be opened up for scrutiny.

For the first time, allegations against the Franciscan order over the actions of the Rev. Cimmarrusti will be heard in court.

"It's hurtful to everybody," said Tom West, vicar provincial for the Franciscan order. "We're poking at these wounds all over again.

"We're talking about incidents that happened 35 years ago," he said. "It's always hard for the older guys to see this in the press and to read about it."

In the meantime, Mr. Fericano and Angelica Jochim, a marriage and family therapist who counsels those who have been affected by sexual misconduct, have been preparing the community for what to expect. They have met with parishioners who attend Mass at the Mission, and Ms. Jochim will meet with other Catholic groups.

Mr. Fericano, a writer who lives in the Bay Area, said he hopes the cases are settled out of court. "Every time Mario's picture is in the paper, it causes new pain for victims," he said.

As part of his own healing, he and another alleged victim, John McCord, formed an organization called SafeNet that helps victims reconcile and deal with their abuse, and he has posted dozens of pictures of St. Anthony's on his Web site, www.mysafenet.net. The physical artifacts he saved are collecting dust in a trailer because there is no space at the Mission to display them, the friars say.

The old cross that sat on top of the administration wing for nearly a century, now covered in rust and mildew, toppled to the ground on the day that St. Anthony's sold -- a chilling coincidence, Mr. Fericano said. Students at Santa Barbara Middle School, a private school that leases part of the building, now lounge on its stone stairs in baggy jeans during class breaks.

The memories of St. Anthony's are distant, and bittersweet, said the Rev. Richard Juzix, who graduated from the school in 1965 and is now pastor of the Mission parish.

"So many many people have good memories there," he said. "Those feelings are now mixed because of what we've learned about what some of the friars did. The memories are not completely wonderful, but they're not all painful either."

e-mail: mevans@newspress.com

F.Y.I.

Angelica Jochim, pastoral outreach coordinator who works with victims, families and others affected by the sexual abuse scandal: (800) 770-8013, (805) 569-5408, Ext. 2#, angelica.jochim@att.net.

SafeNet, an organization run by Paul Fericano and John McCord, two sexual abuse victims, that provides resources and information to help victims reconcile with the Franciscans: www.mysafenet.net. (650) 588-2665.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.