Expert Provides Unique Perspective on Pope's First Year

By Bill Tammeus

The Kansas City Star

April 15, 2006

http://www.kansascity.com/mld/kansascity/news/local/14344753.htm

"I think sociologically there is no Catholic Church in the United States. What you have are multiple Catholicisms. And the question really facing Benedict, as far as the American church is concerned, is how do you bring those tribes into conversation."

— John L. Allen Jr.

|

| John L. Allen Jr. |

When Joseph Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI a year ago next week, his stern reputation led people to expect a hard-line enforcer of Catholic doctrine.

|

|

|

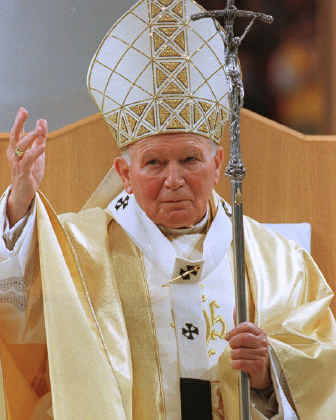

Pope Benedict XVI, right, came to power a year ago after the death of Pope John Paul II. Benedict had a hard-line reputation but has been remarkably open, says Vatican expert John L. Allen Jr. Photo by the Martin Oeser/AFP |

That, after all, had been his job as a cardinal working closely with Pope John Paul II, who died April 2, 2005. But instead of acting like "God's Rottweiler," as he was known, Benedict has come across as open, friendly and even a little kicky — an apt description for a guy who wears red Prada shoes under his robes.

|

|

To journalist John Allen, the story of Pope Benedict XVIís first year is what hasnít happened. Photo by the National Catholic Reporter |

|

|

Pope Benedict XVI oversees a global church in which Americans make up only about 6 percent of members, while residents of the Southern Hemisphere now make up a majority. |

To get an insider's assessment of Benedict's first year, The Kansas City Star interviewed John L. Allen Jr., Rome correspondent for the Kansas City-based National Catholic Reporter and commentator for CNN. Allen was here recently to visit the NCR staff and promote his new book, Opus Dei, about that controversial Catholic organization. His responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Tell us about the pope's first year.

A. The big story is what hasn't happened. There were these expectations that we would be saying Mass in Latin. There would be this great flushing sound as all the dissidents were drummed out of the church. Obviously none of that has happened.

There's nobody who has a deeper sense of the church's tradition than he does. And that imposes a kind of caution, a slowness about any kind of change.

And I think the other thing that those of us who covered him on a daily basis understood is that he makes a very sharp distinction between what he would consider to be matters of faith and morals and everything else. He really is remarkably consultative, remarkably open. He wants to listen and act on the basis of consensus.

That has meant that the only really serious public criticism of the pope actually has come from the Catholic right. A prominent American conservative told me, "We thought we were electing Ronald Reagan, and we got stuck with Jimmy Carter." I think that's due to the fact that a lot of people were expecting immediate and dramatic change.

At the end of John Paul's first year, it was very clear where he was going. There was a very robust reassertion of Catholic identity after a period of modernization.

One year into Benedict, the big difference in public reaction is between those who are paying attention and those who aren't. The truth is that people who are papal aficionados Ö by and large are very impressed. He's incredibly erudite and an extremely talented communicator. He's actually popular with the public. He draws big crowds.

However, very little of that has penetrated to the broader public radar screen. I think if you talked to the average Catholic in Kansas City and asked, "What do you think of the new pope?" they probably could tell you he put out something on gay priests and they heard that he wears Prada shoes. And that's about the only impression they have.

What was your reaction to Benedict's first encyclical, "God Is Love"?

The document has two sections. The first is this philosophical and spiritual meditation on love. The second is a more concrete examination of the world's Catholic charitable institutions.

The first section is entirely his work. And if you want a clue into his mind, that's where you go. The final section is more of a committee thing. My analysis is that basically the guy understands that the church in many ways for a modern 21st-century technical world has got an unpopular message. Its message on gay marriage, on abortion, the nature of the family — these are all things that a lot of people just have a hard time buying.

He understands that part of the reason people don't buy it is that they see it as a power-based legalism. To these people, the church is a defensive institution afraid of modernity.

I think the encyclical was an attempt to change the terms of the debate. That is, "You may not agree with the specific conclusions we have, but at least give us credit for our intentions. I mean, we're not telling you these things because we want to control you; we're telling you these things because we want you to experience real happiness and real love. We want to set you free to be the kind of people God intended you to be, and you'll experience the kind of love that lasts."

It certainly doesn't mark any retreat from his position on these issues. (But) you don't change hearts and minds through excoriation. If you're going to persuade people, the first thing you have to do is be a credible witness to love. That's what the encyclical was meant to be.

Talk about how the estrangement of the American church from the Vatican might be affected by Benedict.

So far I don't think the dynamic has changed very much. Those elements in the American church that were estranged from John Paul II are, to some extent, just holding their breath now. Some even cautiously say they like some of what they've seen.

But I think most of them are convinced that this is the eye of the storm. Conversely I think those people who were really cheered by John Paul II certainly think Benedict's got his heart in the right place, though they've been a little disappointed he hasn't been more aggressive.

The thing to remember is that when we talk about American Catholicism, we're talking about 67 million people. It's unbelievably complex.

Certainly under John Paul II, those most attracted to the priesthood tended to be more conservative theologically.

But as for the generation that's 26, 27, 28, my impression is that the left-right categories just don't work in trying to analyze where they're coming from. Yeah, they do have a higher sense of the ordained priesthood. They're suspicious of democratization. They're certainly very committed to the teaching of the church right down the line.

But they are also very committed to the social doctrine of the church. That then begins to look liberal. They're very committed to John Paul's style of meeting people in the street, evangelization, speaking their language, none of which was the traditional clerical way of behaving.

The problem in the American church is not so much that it's polarized between left and right. The problem is that we've got Catholic tribes.

We've got the liturgical traditionalists, the charismatics, the neo-cons, the social justice people, the church reform people. And they move in their own little self-contained circles. They go to their own conferences, read their own publications, have their own heroes. And very rarely do they step out of those little ghettos and encounter one another.

I think sociologically there is no Catholic Church in the United States. What you have are multiple Catholicisms. And the question really facing Benedict, as far as the American church is concerned, is how do you bring those tribes into conversation. And I don't think there's any magical solution.

But, to be honest, the kind of conversation we're having right now is going to be increasingly irrelevant in the global Catholic scene, given the fact that most Catholics in the world today live in the global South — it's 800 million of about 1.1 billion.

Americans are 6 percent of the global Catholic population, and we will decline as the rest of the world increases. So this split between left and right — the bishops from Africa or Asia don't have much tolerance for it. It's just not a problem that they recognize.

Their problems are much more basic: Two-thirds of their people are HIV-positive. Three-quarters of their people live on less than $2 a day. They're dealing with corrupt governments.

The growth of Christianity in the Southern Hemisphere is not happening just in Catholicism.

Oh, all across the board. Sure. But the Catholic Church is international by design. Which means that Protestant Christianity in Africa can just do its own thing without much reference to the rest of the world. But inevitably what goes on there in some long-run sense does involve Catholics because all of a sudden bishops from the African church are sitting in Vatican offices and affecting policy and making documents that also apply to us.

Americans — especially these people who feel most disenfranchised — are going to cut less and less ice. I would say that for American Catholic liberals, what I'm calling the upside-down church — the church that was driven by the North and now will be driven by the South — is going to be great news on peace and justice issues, but it's going to be a tremendously hard sell for them on things like lay empowerment and sexual morality, because if you think the Catholic Church is a little rigid now, wait until the shots are being called by Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Benedict has said some progressive things about interfaith dialogue. Is he likely to continue John Paul's work on better interfaith relations?

Benedict clearly is committed to continuing the dialogue with other religions. On the other hand, I would say that Islam is actually one of the few areas of contrasts between Benedict and John Paul.

John Paul basically was a dove when it comes to Islam. He met with Muslims more than 60 times, was the first pope to enter a mosque, and his approach was, broadly speaking, to reach out to moderates, to never say anything inflammatory or derogatory or provocative if he could avoid it.

That was the dove agenda. But it stuck in the craw of a lot of people in the church who felt we have to practice something more akin to tough love, especially around issues of reciprocity.

To give you a specific example: If Saudi Arabia's government can come into Rome and spend $65 million to put up the largest mosque in Europe, which they did, protected and supported by the city of Rome, then maybe the church should be able to build churches in Saudi Arabia, which it can't.

I think we're getting a more hawkish line. Not that he's going to shut down dialogue. Not that he doesn't want good relations. But he's not going to do it at the expense of what he would see as truth.

If I were going to make a list of substantive changes between the papacy of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, this would be somewhere near the top of the list.

Will this change be effective?

It's hard to say. But what this will do is make those Catholics who are frustrated by all this feel better. A lot of people feel that the analogy is the church's relationship with the Soviets. Under John XXIII and Paul VI, the dove line predominated. And it didn't seem to change anything. Then John Paul came along with a much stronger challenge, and the walls literally came tumbling down.

If people who are upset at the church were Protestants like me, they might break off into another church.

Right. And that may be the choice some people make. Some have. The schism in the Catholic left is a multiphase process. First there's an internal schism, where you just walk around cursing people and (ticked) off at authority, even though you're going to church on Sunday.

Then you self-select to be in a "progressive" parish, therefore reinforcing you in that choice, and you become even more alienated. Then what a lot of these people do is to spin off into another religious community, like becoming an Episcopalian.

The Catholic right, when it goes into schism, it announces it. It finds a bishop.

To reach Bill Tammeus, call (816) 234-4437 or send e-mail to tammeus@kcstar.com . Visit his Web log at http://billtammeus .typepad.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.