By Renee Schafer Horton

Tucson Citizen

Novemebr 20, 2006

http://www.tucsoncitizen.com/daily/opinion/33160.php

Nearly five years ago, I sat in a sunlit dining room in a house tucked off East 22nd Street and made Bishop Manuel Moreno cry. We were in his home, far from the interruptions and eavesdropping of the diocesan offices, to do an interview for an article I was doing about his silver jubilee as a bishop.

We sat at his dining room table and went through the details of his life: son of Mexican immigrants, young migrant farmworker, first in his family to go to college, graduate of UCLA with a rabid devotion to the Bruins and the Dodgers, seminarian, ordained priest with a deep love of parish life, and, in spite of his protests, eventually a bishop.

|

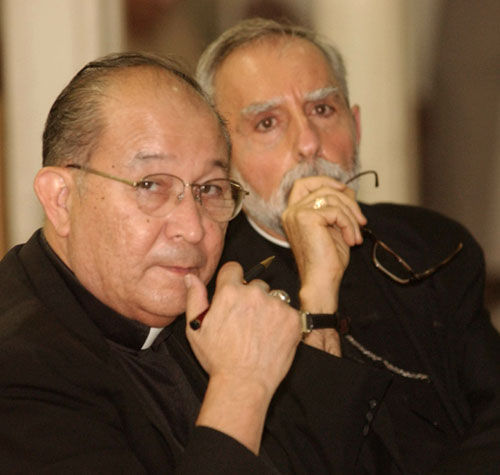

| LEFT: Bishops Manuel Moreno (left) and Gerald Kicanas listen to Catholics who were invited to speak out on any topic that concerned them. ABOVE: Manuel Moreno’s official portrait in 1982 when he was named bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Tucson RIGHT: Bishop Moreno is greeted by Catholics at the Tucson Community Center, now the Tucson Convention Center, during his installation as bishop of Tucson in 1982. |

When we got to present-day events, I asked Moreno about the clergy sexual abuse crisis. I wanted to know one thing: When he'd heard reports of abuse and then confronted priests about the allegations, why did he believe the priests' contentions that abuse had not occurred?

"Because," he said, without hesitation, "why would a priest lie to his bishop?" He looked at me as if I might have the answer, his eyes nearly begging me for one. Then he broke down, apologizing between sobs for being unprofessional.

In nearly two decades of interviewing all manner of clerics, from newly ordained deacons to the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, my questions have never even made one flinch, much less cry.

|

| LEFT: Bishops Manuel Moreno (left) and Gerald Kicanas listen to Catholics who were invited to speak out on any topic that concerned them. ABOVE: Manuel Moreno’s official portrait in 1982 when he was named bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Tucson RIGHT: Bishop Moreno is greeted by Catholics at the Tucson Community Center, now the Tucson Convention Center, during his installation as bishop of Tucson in 1982. |

I attribute this to one thing: Manuel Moreno lacked the self-preservation and politicking gene that so infects, perhaps by necessity, the clerical state. With Moreno, what you saw is exactly what you got.

That morning, what I saw was a man empathizing with children who had suffered at the hands of clergy because he intimately felt their betrayal by those clergy. The abusers had been trusted, by Moreno and the victims, by virtue of their ordination. Their lies were something he could not comprehend.

Approached others as though all were honest

Moreno did not understand duplicity because, as many of his admirers have said, he was a man without guile. Because of that, he approached others as though they, too, were always honest, always seeking the best, always supporting the truth.

"I don't believe the man could have lied in his life," said Rabbi Samuel Cohon, who partnered with Moreno six years ago to build bridges between the Jewish and Catholic communities. In that effort, the two became close friends, often meeting for lunch and ecumenical endeavors.

"I do not want to say he was simple, because that diminishes the man. But I want to explain that he had no pretense, no artifice, no calculation in him," Cohon said. "I think he absolutely embodied the religious spirit in humanity. He taught me a great deal about spirituality just by his living. I felt a close kinship with his heart and I will miss him."

|

There are hundreds of people in the Diocese of Tucson who could say the same thing because Moreno was one of the few people in the world who, when acting interested in you, actually was interested in you. His gift, some might say his fault, was his instinctive pastoral response. If you were suffering, he was suffering. If you were full of joy, he literally beamed. If you were persecuted, he was persecuted.

I know this personally from my time as a columnist for the diocesan newspaper. During those two years, pressure came to bear to pull my column from the paper, since it sometimes dealt with controversial church topics.

Empathy was ever-present in the bishop

Moreno could have chosen, as many bishops across the country have done, to eliminate any questioning voice from the paper by cutting the column. But instead, as Monsignor Tom Cahalane, pastor of Our Mother of Sorrows Parish, reminded me recently, "He stood behind you against the complaints of people who just did not understand because he did understand."

Jack Cotter, who worked for Moreno for 17 years as CEO of Catholic Community Services, said empathy was ever-present in the bishop. Cotter and Moreno would have quarterly lunches after Cotter's 1999 retirement to catch up on each other's lives, and the last time they met was just days before Moreno became ill.

"I have a lasting thanks to God that I took him to lunch last Thursday," Cotter said, referring to Nov. 9. "In his presence you always felt a sense of peacefulness that you were totally embraced by him, that his focus was completely on being with you. For a man who was beset with many health problems in his later years and excruciating burdens to carry as bishop, you would never have known his suffering."

It was ironic that Moreno spent his retirement years at Our Mother of Sorrows, since Moreno had been accused by some of covering up the clergy sex scandals and, as Cahalane said, Our Mother of Sorrows "was sort of ground zero in the sex abuse crisis."

"In the process of getting to know him on a personal level, the parish came to see him as a dear friend and encountered him as one of us," Cahalane explained. "There was a sense of reverence and Otherness that came through him that I don't think he was even aware of, but we saw it.

"When they were putting him on the stretcher into the ambulance to take him to the hospital, he looked at me with such a wondrous expression of gratitude and said, 'It was such a wise decision for me to come to this house.' And he was right, it was. We were all very blessed in the relationship."

Legacy was not only large deeds

There are people who would say Moreno's legacy lies in large deeds over his 21 years as bishop: his work with the mid-1980s amnesty movement, his help establishing the Pima County Interfaith Council, his efforts with community organizing in impoverished communities, his push for Tucson's first gun "buy-back" program, the growth of Catholic Community Services, building 11 new parishes and elevating women to canonical positions in the diocese.

For me, Moreno's legacy will always be this: One day in 2001, I was tagging along as he showed a newcomer St. Augustine Cathedral. We walked in just after 12:30 p.m. and observed a rumpled man approach the priest who had celebrated the noon Mass. He was disheveled, hat in hand, wearing the demeanor of the homeless who frequent the cathedral to escape Tucson's heat.

|

There was a brief conversation and the man shuffled out one of the cathedral's side doors. At that moment, the priest saw Bishop Moreno and came to say hello. Moreno asked him what the man had wanted.

"Confession," the priest said. "I told him to go to the office and make an appointment."

When someone approaches a priest for confession outside the regularly scheduled Saturday services, that's usually the kind of person who won't bother coming back if turned away. This is something every lay person knows, but clerics sometimes forget.

An instance in which he didn't rebuke and didn't approve

Certain bishops might have rebuked the priest for his pastoral insensitivity. Others might have sympathized with his busy schedule, tacitly approving of his pastoral insensitivity. Moreno did neither. He simply turned away from his guest and the priest and broke into a jerky, slow jog - his Parkinson's' disease showing - heading out the side door through which the man had left.

I followed a few minutes later and found the bishop at the corner of the cathedral, distressed that he'd been too slow to reach the man and offer confession.

This was the kind of person Moreno was. He knew that if Christ was to be present in this world, He could only be present through his people. And more than anything else, Manuel Moreno - migrant farmworker, university graduate, humble priest, bishop - was one of God's people. One of the best.

1982 photo by the Diocese of Tucson

2003 photo by TRICIA MCINROY

1982 Citizen file photo

Renee Schafer Horton is a Tucson-based freelance writer specializing in religion and family issues. She covered the Catholic Church specifically from 1983 until 2002, with more than 400 articles and columns published in Catholic newspapers and magazines in Texas, Hawaii, Arizona, Chicago, Missouri and California. From 2000 to 2002, she was a staff writer and columnist for the Catholic Vision, the Diocese of Tucson's monthly newspaper.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.