Financial Struggles Could Trickle down to Local Parishes

By Dan Horn

Cincinnati Enquirer

December 31, 2006

http://news.enquirer.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20061231/NEWS01/612310366/1077/COL02

Money is so tight at the Archdiocese of Cincinnati that the central office is now taking a bigger share of donations from its parishes' Sunday collection plates.

Church officials also are considering cutting staff - through attrition and, possibly, layoffs - and are pushing parishes to repay tens of millions of dollars in outstanding loans from the archdiocese.

|

|

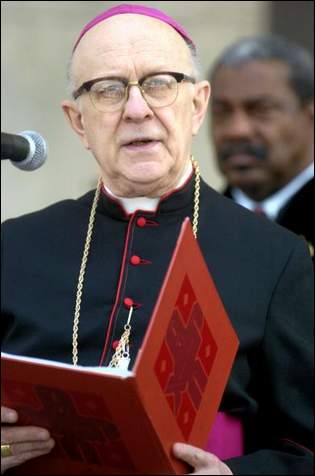

Archbishop Daniel Pilarczyk says the Archdiocese of Cincinnati is in trouble if nothing is done to fix its financial situation. Photo by The Enquirer / Carrie Cochran |

Archbishop Daniel Pilarczyk said he knows the measures are painful, especially for struggling parishes with their own money problems.

He said he has no choice: Without more revenue, the 19-county archdiocese could be out of money within three years.

"If we do nothing, we're in trouble," Pilarczyk said. "The financial policies of the archdiocese will have to be a lot tighter than they have been. The time comes when you run out of money."

The archdiocese's financial woes have been building for years because of an economic slowdown, rising insurance premiums, declining donations and the costs associated with the clergy-abuse scandal.

The result is six consecutive years of budget deficits that drained the archdiocese of almost 60 percent of its assets and reserves, which have fallen from $88 million to $36 million since 2000.

Unless something is done to stop the bleeding, a range of jobs and services could be at risk.

The archdiocese has about 140 full-time employees, 192 active priests and another 86 retired priests, according to the archdiocese's Web site.

Services include youth ministries, educational programs, food pantries, charities for the poor and sick, marriage counseling, aid to inner-city Catholic schools and dozens of other programs.

Some vacant archdiocese jobs have been left open for months, and the archbishop said staff layoffs are "not off the table."

Pilarczyk said he does not expect the archdiocese's problems to close parishes or schools, because they are responsible for their budgets and fundraising.

The archdiocese essentially acts as a home office for its 222 parishes and cannot simply raid their bank accounts.

But many parishes are hurting, too. If the archdiocese pushes for debt collection and takes a bigger share of weekly donations, financially-strapped parishes will be squeezed even more.

The hardest hit could be urban parishes with shrinking populations, rising costs and schools to support.

"It really adds to the financial pressure," said the Rev. David Lemkuhl, pastor at St. Margaret of Cortona in Madisonville, which also has a school. "If they push us too much, it's going to collapse."

A NATIONAL PROBLEM

Dioceses across the country face similar troubles, and a few have declared bankruptcy in the wake of large financial settlements of clergy-abuse cases.

For most, including the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, money was a problem long before the abuse scandals erupted in 2002.

"The finances of most dioceses have been in trouble for years," said Charles Zech, director of the Center for the Study of Church Management at Villanova University. "This didn't sneak up on us."

Zech said a recent study found American dioceses typically ran a deficit in at least one of the past three years. For large dioceses, such as Cincinnati, the average is one deficit every two years.

By that measure, Cincinnati is worse off than most.

The archdiocese's string of six straight annual deficits began in 2001, when the prior year's surplus of $2.9 million turned into an $8.3 million deficit. The deficit now stands at $5.8 million.

Zech said the problem is the "three-legged stool" that props up most dioceses: an annual fund drive, investment income and the assessment, or tax, on donations to parishes. All three legs have been shaky recently.

Investment income slumped with the stock market for several years. The 5.7 percent assessment on parishes remained the same for a decade. Support for the annual fund drive dropped sharply after the clergy-abuse scandal.

"One of the major reasons collections are down is that this is a major way people can express themselves," said Kris Ward, leader of the Dayton affiliate of Voice of the Faithful. "There is a trust that has not been rebuilt since the scandal."

The direct cost of the scandal is about $3 million in legal fees and another $3 million for a settlement fund, but the financial impact goes beyond those numbers. Catholics have focused their anger about the scandal on the archdiocese and Pilarczyk. That, in turn, has affected the bottom line.

Donations to the archdiocese's annual fund drive have tumbled from $4.4 million in 2001 to $3.6 million this year. Donations to parishes, meanwhile, are up slightly over the same period.

"I think it has hurt," Pilarczyk said of the scandal. "People will give to their parishes because they'll say, 'I like our school and our priest, but not that SOB downtown.' "

'ANOTHER BILL TO PAY'

He said the first step to fixing the budget problem was increasing the assessment on parishes in November, from 5.7 percent to 7.2 percent. It will jump again to 8.7 percent in 2008.

The assessment, which draws on weekly collections and fund drives, brings in about $9 million a year. The increases are expected to add millions of dollars more to that total.

Of course, that means parishes will get millions less.

"I look at the assessment as income tax," Pilarczyk said. "Nobody likes a tax increase."

Despite the increase, the assessment here is comparable to those in other dioceses. Youngstown's is 8.5 percent. Cleveland's is 11.5 percent for parishes with schools and 16.5 percent for those without.

Covington, a smaller diocese with lower costs, has a 6.75 percent assessment. The Kentucky diocese expects to balance its budget this year, despite an $84 million abuse settlement that was covered by insurance and property sales.

The higher assessment in Cincinnati is more bad news for struggling parishes, which face the same financial pressures as the archdiocese.

"Like any kind of tax, it is a necessary part of doing the business of the church," said the Rev. Andrew Umberg, pastor at St. William in Price Hill. "I understand the need to do these things, but that doesn't make it any less painful. It is another bill to pay at a time that our parish is struggling."

He said St. William now pays about $30,000 a year in assessments and will pay about $40,000 by 2008. That's a lot of money for a parish and school that survive on a $1.5 million budget.

The impact of the increases will technically be the same for all parishes because they pay the same flat rate. However, healthy, stable parishes will handle it better than struggling parishes.

Another problem for many parishes is debt. St. William and St. Margaret owe the archdiocese $1 million and $200,000, respectively, in outstanding loans and unpaid assessments.

Some of that money went toward construction costs and some went to offset the cost of running the parishes and schools. The archdiocese recently put a moratorium on all construction loans.

Overall, parishes owe the archdiocese more than $100 million, in part because parishes have for years considered paying the debt a low priority.

"We have been doing a gentle subsidizing of parishes by not pushing for repayment of debt," Pilarczyk said. "What we're saying is that was wonderful, and we're happy we were able to do that, but it's over.

"From now on, you pay what it costs."

URGING CATHOLICS TO GIVE MORE

Lemkuhl said he knows his parish owes money, and he understands why the archdiocese wants to collect.

He's just not sure how St. Margaret's can pay.

Weekly collections don't even cover the church's $224,000 budget, let alone the $753,000 needed for the school. The parish survives on weekly bingo games, its annual festival and other fundraisers.

"We'd find it very difficult to pay those bills back to the archdiocese," Lemkuhl said.

It's unclear how aggressive the archdiocese will be in seeking repayment, but Pilarczyk said it's a priority. The hope is higher interest rates will encourage parishes to start paying more.

Pilarczyk also said the archdiocese will make more appeals for help directly to Catholics. The goal, he said, is to rebuild some of the trust lost during the abuse scandal and to convince Catholics that giving to the church is "a part of Christian living."

"Ultimately, we depend on free-will offerings," Pilarczyk said. "If people don't like the product, they are less likely to be generous. We have no power of compulsion."

The archdiocese is not alone in seeking more help from its people.

Zech said the average Catholic household gives about 1 percent of its income to the church, compared with 2 percent for Protestant households. If Catholics gave at the same rate, he said, they would add about $7 billion a year to church coffers nationwide.

Pilarczyk said Catholics need to understand what's at stake. Without more money, the only option is to cut jobs and services.

"You can choose to face it or not," Pilarczyk said. "If you don't, you end up in the poor house. And we're not going there."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.