To Protect Children, Delaware's Baptist Churches Join National Policy Re-Examination

By Gary Soulsman

News Journal [Delaware]

March 3, 2007

http://www.delawareonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070303/LIFE/703030305/1005/LIFE

Though Southern Baptists in Delaware haven't faced the kind of abuse scandals that have troubled the Catholic church, many Baptist ministers are working to make sure children are safe in churches.

The issue was pushed into the national spotlight last week when a Texas abuse victim challenged Southern Baptists across the nation to do more.

|

|

Two-part name tags are a security measure for children at Ogletown Baptist. The child wears one card, the parent takes the other. Photo by The News Journal / Matthew Jonas |

Here in Delaware, the call for action was a bit surprising for the Rev. Jim McBride, the director of missions for the 30 churches in the Delaware Baptist Association.

In the 16 years that he's served as director, no one has brought a case of abuse to him, he says.

At the same time, he believes there is merit in having a broad discussion on this matter. Southern Baptists have 43,000 U.S. churches, including 500 Maryland and Delaware churches serving 100,000 members in 11 associations. It is the nation's largest protestant faith.

At the core of activist Christa Brown's message is this: Each Southern Baptist church governs itself. Churches voluntarily belong to regional and national associations. So no one is in charge of tracking abuse allegations or monitoring ministers with credible allegations.

At the same time, steps have been taken in individual churches in the wake of the priest abuse scandals that have rocked the Roman Catholic church in recent years.

|

| Connie Zinn, children’s minister at Ogletown Baptist Church, explains security measures. |

"One of my responsibilities is the proper care of children," McBride says.

Two years ago there was a regional training seminar on how best to protect Baptist children attending churches in Delaware and Maryland. Next year, McBride wants to hold a training for local churches.

"I don't want to wait for something bad to happen," he says. "I think there are a lot of churches that have not given this issue much thought. They are trusting Christian people. But we live in a society where we can't just take that approach."

He wants to see more churches take up this cause and praises the efforts of the 2,000-member Ogletown Baptist Church, which has implemented an array of protections similar to the ones now mandated by the Catholic Diocese of Wilmington. The Ogletown protections include:

•Sign-in sheets and name tags for parents and children when young people are dropped off for events.

•Background checks on all the ministerial staff before they are hired, as well as for volunteers who help with children.

•Rules requiring that two nonrelated adults always be with children, never one adult alone with a child.

"I have a passion to do this well," says Connie Zinn, the church's minster to children and preschool. "I truly believe that children are safe at our church."

Search for abuser met resistance

For Southern Baptists, this issue has come to the fore in the last three years partially because of Brown, 54, of Austin.

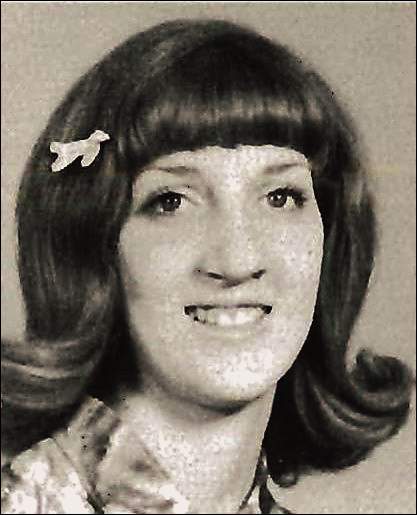

|

| Christa Brown was abused by a Dallas pastor in the late 1960s. |

Growing up in the Dallas suburbs in the late '60s, she was often in the First Baptist Church of Farmer's Branch for everything from Bible study to piano lessons.

"It was my life," she says from her Austin home. "The only thing I wanted was to know God's will and do God's will."

But as a 16-year-old, a self-described naive girl who had never been on a date, her life took a different turn.

A pastor there, the Rev. Tommy Gilmore, sexually abused her, Brown says. When she told the minister of music, he encouraged her to keep the matter quiet, she says.

Years later, after therapy, she wanted to make sure Gilmore was not in ministry. Church leaders she contacted didn't know where he was, and the Southern Baptist Convention wrote her in 2004 saying it had no record of Gilmore in ministry, she says.

But in 2005, she tracked Gilmore to the First Baptist Church of Oviedo, where he was working with youth, after having left a megachurch in Atlanta where he had served for 19 years. She says he'd worked there with a former Southern Baptist Convention president, the Rev. Charles Stanley.

Hoping Farmer's Branch might still take action, she wrote an open letter and placed it on cars in the parking lot of the Dallas congregation. The response of the church's lawyer: Drop the matter.

"I felt betrayed by all levels of the denomination," she says.

So she filed a civil suit against Gilmore and her Dallas church, First Baptist Church of Farmer's Branch. The church music minister, James A. Moore, admitted that he knew of the situation, and last January the church sent her an official letter of apology for Gilmore's abuse.

Gilmore also resigned from his Florida church, she says.

Despite that vindication, Brown is frustrated and convinced that the Southern Baptist denomination needs to change. She also wonders how many others who had been abused gave up their search for justice when they met resistance.

"Where's the outrage on behalf of victims?" she asked.

A lawyer, a wife and a mother, Brown joined SNAP (Survivors' Network of Those Abused by Priests and other Clergy). With 8,000 members, SNAP is the largest organization of clergy abuse survivors in the country.

And last year, she began writing op-ed pieces and started a Web site (www.stopbaptist predators.org). Since then, she says, she has networked with about 40 victims from Southern Baptist churches who've shared their stories.

On her Web site she writes: "To this day, I wonder whether anyone has informed all the many people whose kids interacted with Gilmore in Atlanta.

"Southern Baptist leaders were informed, but what about all the people in the pews? Why don't Baptist leaders use the power of the pulpit to speak out with candor about ministers who are credibly reported for sexual abuse of a kid?"

Requests for reforms

Most recently, Brown has approached the Southern Baptist Convention about reforms. The convention is a co-operative ministry that serves the 16 million members.

Brown's requests for reforms include:

•A funded review panel, with a toll-free number, to keep a data base of names. The panel would also look into allegations.

•A no-tolerance policy, meaning that a credible abuse allegation would result in a pastor not being permitted to hold a position of leadership.

•That mission boards commit to withdraw support from ministries employing pastors with records of abuse.

D. August Boto, a lawyer with the executive committee, said "our hearts are truly broken when we hear of such abuse, and we will continue to encourage Southern Baptist churches to address this deplorable behavior."

He said the Southern Baptist Convention has long encouraged the reporting of abuse crimes to police, and that churches should protect children by having ministers and other adults go through criminal background checks before working with youth.

He also said it's not possible to create an abuse review panel given the structure of the denomination, with autonomous churches who voluntarily take part in the convention. The Southern Baptist Convention "has absolutely no authority over any Southern Baptist church."

But Brown points out that the Conference of Catholic Bishops initially said it could insist on no standards for dioceses, given that local bishops had control. However, as the importance of the issue heightened -- the church has now paid out more than $1 billion in settlements -- the bishops did set standards and compliance reviews, she says.

Given that Baptists collaborate on missions and the creation of teaching materials, surely they could do more on the issue of abuse, Brown says.

"I absolutely believe there are wonderful Southern Baptist pastors," she says. "I also believe that the problem is enormous."

Local pastors say the protection of children needs more regional discussion. As director of missions for the Delaware Baptist Association, McBride makes that point.

So does Pastor David Phillips of Mission Fellowship in Middletown. As Southern Baptists, worshippers often feel that no one tells their church what to do, he says, but an awareness of how to protect children is essential.

Contact Gary Soulsman at 324-2893 or gsoulsman@delawareonline.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.