By Julie Lyons

Dallas Observer

March 23, 2007

http://blogs.dallasobserver.com/unfairpark/2007/03/old_habits_die_hard.php

Pastor Sherman Allen's bishop in the Church of God in Christ, J. Neaul Haynes of Dallas, has been aware of paddling allegations involving Allen for at least 17 years.

One of Allen's alleged victims, a woman who identifies herself by the pseudonym "Jill," complained about the paddling to a Church of God in Christ district superintendent in 1989 or 1990, she says. Her complaint led to a meeting that involved Haynes and other COGIC clergymen. Jill and two other women detailed their allegations against Allen at that meeting, with one woman calling Allen's penchant for paddling a "bad habit" that "needs to be broken."

Bishop Haynes' reply, according to Jill: "Old habits die hard."

|

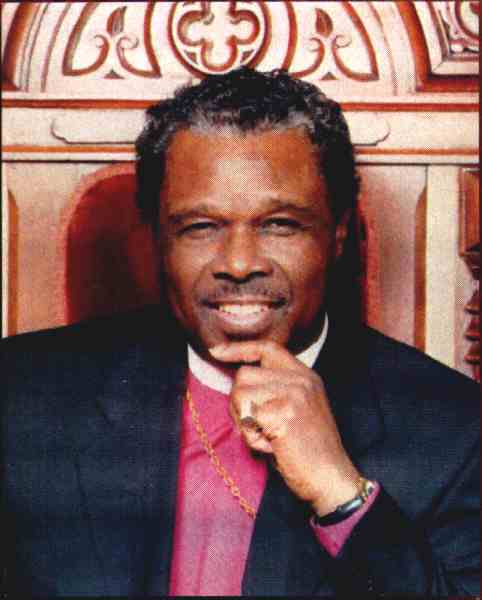

| Bishop J. Neaul Haynes: What did he know about Pastor Sherman Allen, and what did he do about it? |

No action appears to have been taken against Allen, Jill and others say.

Haynes, pastor of Saintsville Church of God in Christ in South Oak Cliff and now the No. 2-ranking bishop in the COGIC (because of the death Tuesday of Presiding Bishop Gilbert E. Patterson), has not responded to two detailed written requests for comment. His church hung up on my assistant when she called last Monday. The Church of God in Christ's general counsel, Elder Enoch Perry III, also hasn't responded to requests for comment.

Pastor Allen's attorney, Frank Hill of the Arlington law firm Hill Gilstrap, did offer a polite "I can't comment" on his client's behalf.

One of Allen's former church members and employees, Davina Kelly, has filed suit against Allen; Allen's Fort Worth church, Shiloh Institutional Church of God in Christ; the Memphis-based Church of God in Christ denomination; and unidentified COGIC officials whom Kelly's attorneys plan to name as defendants at a later date. Kelly claims that Allen repeatedly paddled and sexually abused her. Allen has filed a general denial of the claims.

Since the lawsuit became public in February, seven other women or their family members have contacted Kelly's Dallas-area attorneys, Stan Broome and Matthew Bobo, with similar claims. Read here, here and here for previous Bible Girl columns about the Allen case.

A COGIC pastor has told me about another meeting involving Bishop Haynes and another set of allegations against Allen. (I spoke with several other COGIC sources who confirmed that this meeting took place.)

This pastor, who asked that he not be identified, was present at a meeting in the mid-1990s in which he and several other pastors from Bishop Haynes' COGIC jurisdiction listened as a single woman and a married woman, who came to the meeting with her husband, voiced accusations that Allen had paddled them. The single woman also claimed Allen raped her after forcing her to undress and paddling her so brutally that it left scars. She tumbled down some stairs trying to escape him. Bishop Haynes was present for part of the meeting, the pastor says, but later left and turned it over to a district superintendent, who then led the proceedings.

The pastor I spoke to says he sat right next to Allen, who showed no emotion as the women made their claims. But throughout the meeting, the pastor says, Allen sat with his legs crossed, shaking his foot constantly.

At one point, the woman's husband told Allen that if he ever hit his wife, he'd get a gun and blow Allen's head off. Haynes rebuked him.

After hearing the allegations, Haynes commented that he hadn't heard anything "concrete," the pastor says.

The single woman was disgusted with Haynes' response, the pastor says. She told the men, "I knew I was wasting my time coming here."

Haynes dismissed himself from the meeting, leaving a superintendent in charge. The superintendent, whom the pastor recalls as being very nervous, asked Allen a question about the allegations.

Allen's reply, according to the pastor: "Some of the charges are true, and some charges are not."

The pastor turned to Allen and pressed further: "Which are true, and which are not true?"

"I don't have to answer to you," Allen replied.

"Brother, you're right...but two things are going to happen to you," the pastor says he told Allen. "What goes around, it comes around, and you are going to have to reap what you've sown. And I don't know when it will be, but sooner or later, you're going to be brought to justice.

"And I hope it's soon...you are a disgrace."

The pastor left the meeting realizing that Bishop Haynes wasn't going to do anything about Allen. And, to his knowledge, nothing ever was done.

I should add that the Church of God in Christ is no fly-by-night Pentecostal organization; it has its origins in the Azusa Revival at the turn of the last century and is in many ways the mother of the classic Pentecostal denominations. The Assemblies of God and quite a few other Pentecostal bodies have their roots in the Church of God in Christ and its founder, Bishop Charles Harrison Mason — an extraordinary black apostle who ordained whites as well as blacks in the midst of the Jim Crow era.

If you meet a man who has made the rank of bishop in the Church of God in Christ, you can be assured that he has worked his tail off within the organization for many, many years. In contrast to practices on the fringe of Pentecostalism, being a bishop in COGIC really means something. It is in no way a self-appointed position.

I had the opportunity to interview Bishop Haynes years ago when I was a reporter at the Dallas Times Herald, and I found him to be a gracious and thoughtful man. He oversees many, many churches, and Allen's was just one of them.

Jill's Story

I interviewed "Jill" at length a few weeks ago. Jill, now 41, began attending Allen's church as a child. Her mother was, and still is, a staunch Allen loyalist and Shiloh church "mother." In those early days of Allen's ministry, Jill says, "many" church members actually ceded discipline of their children to Allen through permission slips — Allen retained the only copy, she says.

The permission slips cleared the way, in Jill's case, for repeated paddlings, she says. Jill's story begins with a strained relationship with her mother. Jill has two younger half-sisters who, she says, were treated more favorably by her mother. Jill, in contrast, was perceived as the black sheep, even though she says she "did nothing" and couldn't even if she wanted to, since she lived within the tight confines of Allen's church circle. "I don't know if it goes back to her and my dad's relationship, but it's like she had a problem with me, and it got worse and worse," Jill says of her mother. "I was always treated differently."

Growing up, Jill witnessed some strange scenes in Allen's church. I asked her if she'd heard he was involved in the occult, which had been rumored for years in COGIC circles. "There didn't have to be no rumors," Jill says. "I was there and pretty much saw it." In the church, she said, Allen had a 2- or 3-foot Mary statuette on display — not a typical Pentecostal prop, to say the least. It was "off to the side," Jill says, and it was "actually fading in and out" during a service.

"I just kind of closed my eyes, because I knew I wasn't seeing that," Jill says. "But...this is some crazy stuff. I know what I saw. That's what I saw."

Allen often gave her "healing" potions, she says, some of which made her ill.

The paddlings, she says, began when she was 13. Allen would ply her mother for information about anything Jill had done wrong. Was she acting up in school? Things like that. "That's how he concluded if I should get a paddling or not," she says.

Jill's life was firmly circumscribed by the church — she had to drop everything to accompany Allen and other members to meetings, and he also dictated her circle of friends, she says. When the paddlings started, he always managed to identify something she'd done wrong, thanks to Mom's tattling.

When Allen started paddling her, Jill says, her mother stopped disciplining her altogether. Allen would initiate private meetings with her at his office by telling Jill he needed to see her after church, Jill says. The meetings were supposed to be counseling — to keep her from getting with the wrong crowd. The first time he asked to meet, she says, "I was thinking it had something to do with the church, but it was the lowdown of what he'd been told, I did this and I did that."

In these early years of the ministry — in the 1980s — Allen allegedly paddled her while she was fully clothed. He'd even ask her to choose the paddle — he kept several in a closet; some were thick and some were thin, she says. When given the choice, she'd pick the thin one. He also carried a paddle in a briefcase in the trunk of his car, she says. (Lawyer Stan Broome says he's heard this from several alleged paddling victims.)

Though Jill always made sure she did nothing to trigger a paddling, she says Allen always found something. It could be as vague as claiming "God don't like ugly," an African-American saying that refers to behavior, not appearance. Before whacking her, she says, he'd tell her he had her best interests in mind: "'You know, I want what's best for you. I don't want you to get mixed up with the wrong crowd, being rebellious to God.'"

Then he'd tell her to grab her ankles and pull her dress down tight, so loose clothing wouldn't soften the blows. "I would grab my ankles and bend over...and he'd have me grip my dress, and he would paddle me," she says.

"I really can't tell you how many licks it was, I just know that my bottom was hard — it was purple. It took forever and a day for me to be able to actually sit down...I would almost be sick, but that didn't make any difference to him."

Sometimes Jill would struggle and turn around or cover her rear with a hand to shield the blows. One time he hit her in the wrist while she squirmed, she says, and it "swelled up so big where I just had to hold it to keep the pain down."

The beatings got worse over time, Jill says. Sometimes Allen would sidle up to her in church and ask in a whisper, "Is your bottom still sore?"

"Then he would tell me what to do to soothe it," Jill says. "Soak it in Epsom salts." (Davina Kelly says Allen told her to use cocoa butter.) Her bottom, Jill says, became "rock hard" like a callus.

After the very first beating, Jill says she confronted her mother. Why did she let him do that? "I told her that any time I was out of line or unruly, you took care of that — so why would you even do that? And I told her, you can stop this. She said, 'No, I can't.' I said yes you can — you're the one who started it. And she never did [do anything to stop the beatings]. And it went on and on. And she's still there [in Shiloh]."

It was another story with the two other daughters, Jill says. "He spanked them one time," she says, "and after that she wouldn't let him touch them."

One time Jill confided in an adult church member about the beatings. That member immediately told Allen, she says, "and at that point it really got hard on me."

She also began struggling in school. "My grades went down. I was the very last one in school because I didn't want to go home."

Jill thought she'd found a way out of the pain. At 16, she says, she tried to kill herself by swallowing a handful of pills. But nothing happened.

"I looked at it as I'd be free — it would be my way out," Jill says, fighting back tears. "I didn't have nobody I could turn to. Nobody to lean on. I was cut off from everything. I was cut off from my aunties, everybody. I couldn't talk to nobody. If they wasn't anybody dealing with Shiloh, I could not talk to them."

Allen, Jill says, has a preternatural ability to detect a woman's weaknesses. "It's a mind thing," she says. "And he knows that we at a vulnerable state — he use that. Along with his oils and all his other stuff...It's like he's reading your mind. He'd have this thing where he'd say, 'Look at me. Look at me. Look at my eyes.' He has some kind of control. You're going to do what he say."

Allen often prescribed her potions and herbal remedies, she says, including one that looked like loose-leaf tea and was packed in a plain plastic bag. It made her sick to her stomach, she says. Other times he'd ask her to drink water that he'd prayed over. That made her ill too, she says. She stopped drinking it.

While the beatings weren't overtly sexual, she says, she believed he meant to steer it in that direction. One time, she says, he asked her whether she was on the pill. She said she wasn't. Why not? he asked her. "Because I'm not doing nothing," she replied.

Jill never thought the beatings were justified. She always believed Allen had crossed the line. "When I was young, there was nothing I could do about it," she says. At one point she'd looked up to him as a leader, she says. But after the paddlings started, she says, "I couldn't stand him."

Finally, she says, she realized she "couldn't go through this anymore." She had a boyfriend who found it silly that she jumped every time Allen asked her to do something or go with him to a meeting out of town. "Then I sit back and saw that that was exactly what was going on," she says.

The final beating — and the last straw with Allen — occurred when Jill was three months' pregnant, she says. She was in her early 20s. First, she says, Allen found out she was pregnant and stood her up in front of the church during a service and announced it to everyone. He looked at Jill and said, "I told you that nigger was no good." He cautioned the congregation not to make fun of her because "they were gonna have to deal with him," she says.

"That did not make me feel good," Jill says, "because I know how he did people."

Later they met privately in his office. "He said I was being rebellious," Jill says. "I had some kind of spirit on me. He started this crying act — 'I love you, I love you, I love you...' I was like, yeah, I love you too, but you're not gonna hit me. And we started wrestling and tussling."

Allen, she says, reached for a paddle on a table. Jill fought back, pushing him away as hard as she could. He still managed to get in one lick as she struggled to get to the door. He kept saying her loved her, she says. Jill just told him to let her go.

"I don't know how I got out," she says. "I got out and I just ran up the street. I ran because I refused to lose my baby."

Two hours later, while she was at home, she miscarried. She believes it happened as a direct result of her struggle with Allen.

Later she went to the police, she says. Then, she claims, Allen threatened her. "He told me if I ever tried to ruin him, he would come back for me," she says. "I know how he is and I know the kind of stuff he do. So I didn't try to make no waves. He knew people in high places."

Jill says she approached COGIC authorities when she was 24. She and two other young women asked for a meeting with Superintendent Edward Battles (now deceased), who presided over Allen's district at the time. (District superintendents, however, have virtually no authority over the pastors in their district. The district superintendent is charged with raising a certain amount of money from his churches to make a financial "report" at his bishop's state convocations.)

When they arrived at the meeting at Battles' church, Love Sanctuary COGIC in Fort Worth, Jill was surprised to find several church officials there, including Allen's bishop, J. Neaul Haynes. The meeting was in 1989 or 1990, she says, and Allen was not present.

"We had told him about the things that [Allen] was doing," Jill says, referring to the paddlings. "And we was like, we didn't really think this was right. One of the women said what he was doing was wrong, and that he had a habit — a bad habit — and it needs to be broken."

Haynes' reply, according to Jill: "Old habits die hard."

To Jill, the COGIC leaders didn't seem concerned about the allegations. "They didn't believe it," she says. "They just said they'd check into it. And that was it."

Jill never heard again from Haynes or Battles. But she did get "banned" from Shiloh. "The pastor said because of 'all the confusion,' you are no longer welcome at the church, and they [members] were not allowed to talk to me," Jill says.

She knew he meant it, she says, because she was in a grocery store one day and a Shiloh member literally wheeled her cart around and went the other way after spotting Jill. Her mother wouldn't let her sisters talk to her, she says.

For years since then, she says, she hasn't had a normal life. She's never married, never had children. She's experienced serious physical problems. Her relationship with her mother is severely strained. "As long as I was at Shiloh, I was at work, Shiloh people were there, and the minute I'd do something, they'd come calling him [Allen], telling him what I was doing. They picked my friends. They picked where I went.

"This has messed me up," Jill says. "I wasn't able to just have a relationship and have a normal life, period. I had my childhood taken away from me...and it's like I've lost a whole section of my life and can't get it back."

Dallas Observer Editorial Assistant Kaitlin Ingram contributed to the reporting for this column.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.