An Alleged Case of Abuse Is Pivotal to Two Lives

By Sarah Overstreet

News-Leader [Missouri]

April 25, 2007

http://www.news-leader.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070425/OPINIONS/704250313/1006

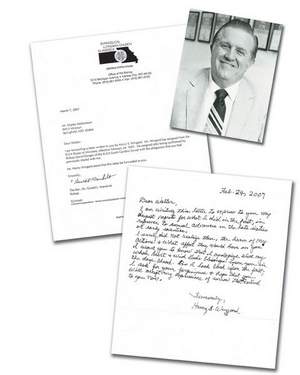

Walter Molkenbur carries two letters around with him: one from a former pastor here in town, and the other from the bishop who now supervises this region.

The 48-year-old Springfield man says the pastor molested him when he was a child, and former Messiah Lutheran Church pastor Henry Wingard has written Molkenbur a letter of apology:

"I am writing this letter to express to you my deepest regrets for what I did in the past, in reference to sexual advances in the late sixties or early seventies," Wingard writes in longhand. "I surely did not realize then, the harm of my actions and what affect they would have on you. I want you to know that I apologize with my whole heart and I wish God's blessings upon you in the the days ahead. As I look upon the past, I ask for your forgiveness and hope that you will accept my my expressions of sorrow that I extend to you now."

|

| Walter Molkenbur Henry Wingard (above) wrote the letter of apology below to Walter Molkenbur. News-Leader photo composite |

| • PDF DOCUMENT: Letter of apology from Henry Wingard |

Molkenbur, much of the time homeless, working sporadically these days and often hard to get hold of unless he contacts us, alleges Wingard lured him into the church and raped him when he was a child.

The other letter Molkenbur carries is from the bishop of the Central States Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Rev. Dr. Gerald L. Mansholt, Kansas City. As an introduction to Wingard's letter, Mansholt writes, "I am forwarding a letter written to you by Henry S. Wingard. Mr. Wingard has resigned from the ELCA Roster of Ministers, effective February 24, 2007. He resigned after being confronted by Bishop David Donges of the ELCA South Carolina Synod with the allegations that you had previously shared with me."

Contacted by phone in his Myrtle Beach, S.C. home late last month, Wingard said he does not remember Molkenbur. Further, he didn't see why any of this was newsworthy now.

"It was 37 years ago, and I don't even remember him," Wingard, 83 and retired, said. "What advantage is there to do something like that (to publicize the story), when I'm taking punishment from all these other places?"

Next, he says, all the media attention the topic of childhood abuse by ministers is blown out of proportion. "It doesn't have to be (such a hot media topic)," he said. "It seems like that's all you hear on the news now."

Why the subject is so important is that so many adults have come forward saying they were abused by clergy. After victims of Catholic priests surfaced, gaining widespread national attention, filing lawsuits and forming support groups, people in other denominations have revealed sexual abuse by clergy.

"Childhood sexual abuse almost invariably causes lifelong, sometimes devastating, harm to victims," said SNAP national director Dave Clohessy from his St. Louis office. "Sadly, the very same personal difficulties that are often caused by the abuse also, to some people, diminish the credibility of victims. People say, 'Why should we believe this person? He has a background of mental instability, criminal acts, addictions, homelessness — I say, 'Why shouldn't he?'"

Clohessy also says that acknowledgement of the abuse by the abuser is essential to the victim's healing. "The unacknowledged wound rarely heals. Any admission or acknowledgement can be an important step towards closure and healing."

And why did Wingard say he wrote the letter to Molkenbur? "I reckon the bishop asked me to." Does he confess to the "sexual advantages" towards Molkenbur he writes about in his letter? Does he say he sexually abused Molkenbur? No, he says, only, "If I did that, I was apologizing for it."

Molkenbur says the letters and recognition of what happened to him are the primary reasons that he went to the synod in the first place. He says the molestation he alleges may not be the reason for the train wreck his life has become, but it has plagued him every day of his life since it happened.

"What I'd really like to do is have a meeting with Wingard and blow my brains out in front of him," says Molkenbur, who readily acknowledges his mental health has been a roller coaster since adolescence. "Sometimes I'm kinda out there," he says. He acknowledges his moods swing dramatically, that he is sometimes unemployed and homeless, often lives in motels and sometimes sleeps in his pickup truck. He has called or just shown up at the News-Leader on several occasions with situations he considers emergencies, has hung up on reporters and then called back to apologize. He once parked his truck on the Messiah Lutheran Church parking lot and called the News-Leader to say he would be sitting in his truck with his dog at the church, praying until the pastor that raped him calls him.

Molkenbur has served almost 13 years in Missouri prisons for first degree burglary, attempted rape, distribution of a controlled substance and attempt to manufacture methamphetamine. He violated his parole both times he was imprisoned.

His attempted rape is one of the first things Molkenbur brings up when he talks about his allegations of abuse against Wingard. "That was a terrible thing to do and I take responsibility for that," he says. "It wasn't right, but I think a lot of my problems come from the abuse."

Mansholt says Molkenbur first came to the current pastor of Messiah Lutheran, the Rev. Dan Friberg, with his allegations, and Friberg contacted Mansholt. Mansholt then told church officials in South Carolina who confronted Wingard. Had Wingard refuted the charges, Mansholt says, the church would have conducted an investigation that may have led to ecclesiastical courts. But in Wingard's case, he agreed to resign from the ELCA's roster of ministers and issue the letter of apology to Molkenbur.

Mansholt came to Messiah Lutheran March 25 to tell the congregation of the situation that had transpired between Wingard and Molkenbur. "I there made a statement publicly to the congregation to disclose that Henry Wingard had been accused of molesting a minor that was not a member of the congregation ... We do the disclosure so that should there be other victims, should there be other things that need to be disclosed, people can come forward ... The congregation took the accusations very seriously."

Mansholt says Molkenbur was told that the disclosure would be made, but not when. Mansholt says that it is ELCA policy to also inform other congregations where a Lutheran pastor has been taken off the roster of pastors. They are: Trinity Lutheran in Georgetown, S.C.; St. Luke's Lutheran in Columbia, S.C. and Hope Lutheran in Midland, Texas. Wingard also served as assistant to the president of the South Carolina synod of the Lutheran Church in America.

So what now for Molkenbur, now that he has the apology he sought? Since receiving the letters and bringing them to the News-Leader, numerous calls to his cell phone have received a recorded answer that the person at that number is not available.

And the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America? Do personnel believe they have any further obligation to Molkenbur? Mansholt says that in some cases, alleged victims are helped with a limited amount of mental health counseling and in some cases other support from the church itself or members. In Molkenbur's case, he is already receiving psychological therapy and is often hard to contact. He says he can't speak more specifically about Molkenbur's situation.

Mansholt says the church has no provisions for any kind of monetary reparations in a case like Molkenbur's, "but any victim certainly has the right in this country to pursue a lawsuit."

Contact columnist Sarah Overstreet at soverstreet@news-leader.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.