Uses New York Connections, 9/11 Cachet to Ease Way for Clients

By John Solomon and Matthew Mosk

Journal Gazette

May 13, 2007

http://www.fortwayne.com/mld/journalgazette/news/nation/politics/17220820.htm

Washington On Dec. 7, 2001, nearly three months after the terrorist attack that had made him a national hero and a little over three weeks before he would leave office, New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani took the first official step toward making himself rich.

The letter he dispatched to the city Conflicts of Interest Board that day asked permission to begin forming a consulting firm with three members of his outgoing administration. The company, Giuliani said, would provide "management consulting service to governments and business" and would seek out partners for a "wide-range of possible business, management and financial services" projects.

|

|

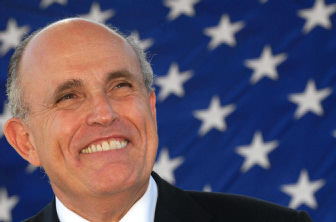

Presidential hopeful Rudy Giuliani negotiated last weeks settlement that ended a federal investigation into the marketing of OxyContin. Photo by The AP |

Over the next five years, Giuliani Partners earned more than $100?million, according to a knowledgeable source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the firm's financial information is private.

That success helped transform the Republican considered the front-runner for his party's 2008 presidential nomination from a moderately well-off public servant into a globe-trotting consultant whose net worth is estimated in the tens of millions of dollars.

In crafting its image, the firm took care to burnish its most valuable asset: the worldwide reputation Giuliani earned for his composure and leadership in the days after the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. "No client is ever approved or worked on without a full discussion with Rudy," said the firm's senior managing partner, Michael Hess, former corporation counsel for the city of New York.

Not surprisingly, a company that markets Giuliani and is run by Giuliani has taken on the characteristics of the politician, who even by New York standards is known for his self-confidence and insistence on doing things his way.

Famously loyal, Giuliani chose as his partners longtime associates, including a former police commissioner later convicted of corruption, a former FBI executive who admitted taking artifacts from ground zero and a former Roman Catholic priest accused of covering up sexual abuse in the church.

Giuliani, grounded in the intricately connected world of New York politics, has been adept at making the system work for his clients. They have included a pharmaceutical company that, with Giuliani's help, resolved a lengthy Drug Enforcement Administration investigation with only a fine; and the horse racing industry, eager to recover public confidence after a betting scandal.

Clients of Giuliani Partners are required to sign confidentiality agreements, so they do not comment about the work they receive or how much they pay for it. Though now running for president, Giuliani refuses to identify his clients, disclose his compensation or reveal any details about Giuliani Partners. He declined to be interviewed for this story. A request to visit his offices overlooking Times Square was turned down.

This story is based on a review of corporate, government and court records, along with scores of interviews with clients and government officials who have interacted with Giuliani Partners.

Hess, the one authorized to speak for the firm, said Giuliani Partners does not want its clients to exploit Giuliani's name and does not engage in lobbying. He said the company carefully chooses whom it hires and represents.

"We're cautious in the right sense of that term. In terms of who we work for. We always want to make sure it is a company that is doing the right thing, that we're proud to represent," he said.

For many clients, hiring Giuliani delivers the political equivalent of a Good Housekeeping seal. Startup companies and clients gain instant credibility as well as the potential to access a vast Rolodex of contacts Giuliani and his partners have amassed over the years.

"His name brings inherent value," said John Mason, chairman of BioOne Solutions, a Florida decontamination company that merged with Giuliani Partners. "If someone has a need in our area, it's unlikely they wouldn't take his call."

Blue-chip clients

Giuliani left office Dec. 31, 2001, with relatively modest means. His final ethics report to the city listed gross assets of between $1.16?million and $1.83?million in 2001; most of that wealth was two Manhattan apartments and some retirement mutual funds. The only source of income he listed besides his $195,000 mayoral income was from renting one of the apartments.

His initial letter to the Conflicts of Interest Board asked permission to begin forming the company in his final days as mayor with three aides he planned to take with him Hess, chief counsel Dennison Young Jr. and chief of staff Anthony Carbonetti. Two others police Commissioner Bernard Kerik and fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen were not mentioned but later came on board as senior vice presidents.

The company opened for business in January 2002, its core values described on its Web site as "integrity, optimism, courage, preparedness, communication and accountability." From an initial group of about a dozen principals and support staff, it has quadrupled in size.

Giuliani, the chairman and chief executive, had little private-sector experience and early on entered into an alliance with the accounting firm Ernst & Young, long a city contractor under his administration. The affiliation brought instant business know-how along with a stable of potential blue-chip clients.

Kerik took the lead building the Giuliani Partners security arm. But even before Giuliani left the mayor's office, city investigators warned him Kerik might have ties to organized-crime figures, a warning Giuliani recently testified that he does not recall.

Kerik abruptly left the company in early 2005, after his nomination to be homeland security secretary supported by Giuliani collapsed. That was a year before he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge that he accepted free work on his apartment from a contracting firm accused of having ties to organized crime.

To replace Kerik, Giuliani turned to former FBI executive Pasquale J. D'Amuro, who had risen through the ranks as one of the bureau's savviest antiterrorism agents to become its third-ranking official.

In 2004, a Justice Department inquiry into the removal of souvenirs from the World Trade Center site disclosed that D'Amuro had asked a subordinate to gather half a dozen items from ground zero as mementos just weeks after the attacks. D'Amuro later acknowledged he kept one piece of granite that he received in June 2003. The FBI took no action, and he donated his memento to the New York FBI office before retiring.

In 2003, Giuliani brought into the firm Alan Placa, an old friend who resigned as vice chancellor of the Diocese of Rockville Centre on Long Island a week after being confronted by Newsday with allegations that former parishioners had been abused. The newspaper published portions of a 2003 Suffolk County grand jury report in which accusers said he used his position to stifle complaints of abuse by clergy.

The Long Island newspaper has reported Placa denied the allegations, was not charged with a crime and is going through a process within the church to clear his name. Placa has been described by the company as a "consultant."

'We don't do lobbying'

Right from the start, Hess said, Giuliani proved to be as "hands-on" as chief executive as he was as mayor. Giuliani demanded daily briefings that were "reminiscent of the staff meetings that we had in City Hall," Hess recalled.

When Hess describes the work of Giuliani Partners, he says it is impossible to pinpoint a single specialty. He did say, emphatically, that the firm has not tried to use Giuliani's political connections to influence federal officials.

"We don't do lobbying," Hess said. "And therefore that is not something where we are running to talk to a regulator or an agency.

In May 2002, Purdue Pharma, a Connecticut-based drug company, hired the company at a time when the DEA and the Food and Drug Administration had begun investigating a wave of overdose deaths attributed to the lucrative painkiller OxyContin. The agencies were looking into the product's illicit use as a recreational drug and were probing security at the company's manufacturing plants in New Jersey and North Carolina.

In a written statement, Purdue announced Kerik would conduct a security review at Purdue's Totowa, N.J., manufacturing plant, while others in Giuliani's firm started designing an early-warning network to spot prescription drug abuse, develop national standards for prescription monitoring and try to increase public awareness.

Behind the scenes, Giuliani began reaching out to old friends in a position to influence the path of the investigation. Government officials said the former mayor contacted then-DEA Administrator Asa Hutchinson, whom he had befriended two decades earlier, and that he dialed up Karen Tandy, who headed a Justice Department task force and later took Hutchinson's place as DEA chief.

In short order, Giuliani arranged a meeting in the conference room of Hutchinson's office.

"The main thing I remember was his commitment to help the company develop safeguards," Hutchinson said. "He was going to bring his expertise to see where security needed to be improved and to provide confidence in the handling of a very dangerous drug."

Cynthia Ryan, who was serving as Hutchinson's counsel at the time, described Giuliani as "advocating for a client."

Laura Nagel, who then headed the DEA's office of diversion control, was not happy. "My reaction was that they went around me," she said of Purdue. "They went and got Rudy. I think they thought they were buying access and insight into how to manage things politically."

A week before the first anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, the former mayor joined Hutchinson and then-Attorney General John Ashcroft for the opening of a traveling DEA exhibit on drug trafficking and terrorism. Giuliani, who as a prosecutor and mayor had emphasized his record fighting crime, also spoke at a luncheon that day that raised $20,000 for the DEA Museum Foundation.

Bill Alden, foundation president, said he did not learn until later that Giuliani was working for Purdue.

In June 2004, the government settled the case by requiring the Purdue Pharma affiliate that ran the Totowa plant to pay a $2?million civil penalty. The drugmaker did not have to admit wrongdoing or take its product off the shelf.

Last week, it settled another federal investigation when the company and three current and former executives pleaded guilty to marketing OxyContin in a way that played down its addictive properties. People involved in the case said Giuliani met with government lawyers more than a half-dozen times and negotiated the settlement.

In 2002, Giuliani Partners landed a $4.3 million contract to advise authorities in Mexico City on how to tackle its crime problems. Giuliani touted the deal during a splashy tour through the city's most dangerous neighborhoods, and his firm delivered a 146-point plan that the city's public security secretary, Marcelo Ebrard, trumpeted far and wide.

Ebrard, now the city's mayor, said the city put panic buttons on public buses and put surveillance cameras in high-crime areas.

But Jorge Castaneda, former foreign minister of Mexico, called the contract a "$4 million publicity stunt." Jorge Montano, former Mexican ambassador to the United States, said, "With all honesty, nothing that they suggested was successful."

The problem, Montano said, was that Giuliani simply recycled ideas that had worked in New York.

"His recommendations were not based on the Mexican reality," Montano said.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.