By Michael Leahy

The Washington Post

December 16, 2007

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/15/AR2007121501916.html

New York was warm on that spring day in 1961, remembers Jack O'Leary, a teacher and role model for 17-year-old Rudy Giuliani, and a confidant for the boy's father, Harold Giuliani. Harold had asked O'Leary, then a member of the De La Salle Christian Brothers, to Sunday afternoon dinner at the Giulianis' home on Long Island. He said he had something he needed to discuss. A puzzled O'Leary found Harold in the back yard, stretched out on a chaise longue beneath a blanket despite the heat, his head on a pillow. His son was standing like a sentry next to his prostrate father.

O'Leary took a seat in a patio chair and listened as a despondent Harold told a troubling story: He had been arrested recently on suspicion of loitering in the restroom of a local public park -- loitering for immoral purposes, O'Leary recalls Harold explaining.

O'Leary glanced at Rudy.

No reaction.

|

|

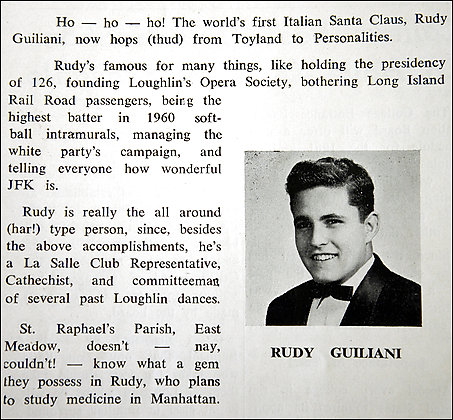

This photo shows Rudy Giuliani in the Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School newspaper during his senior year. The description of Giuliani says he is known for "telling everyone how wonderful JFK is" and that he wants to study medicine. Click on the photo to read the full description. Photo by Giuliani Campaign |

That the police had dropped the matter against Harold, never so much as filing a formal charge, had done nothing to dent his trauma. Insisting to O'Leary that the incident had been a misunderstanding, Harold alluded to his version of what had happened in the park restroom: Suffering from chronic constipation, he had been doing deep knee bends to loosen his bowels. But most of Harold's rambling talk revolved around his only child, and his fear that the incident might forever haunt Rudy.

"Harold had suffered a nervous breakdown over what had happened," recalls O'Leary, sitting in a restaurant in Northern California, where he lives today after leaving the De La Salle Christian Brothers in the late '60s. "He said he couldn't work. He couldn't do anything. But, with all his problems, he was mostly worried over what all of this would do to Rudy."

The younger Giuliani solemnly listened to his father's anguish. "Rudy was very calm -- no crying, no hysterics," O'Leary remembers. "I knew by the way he was acting that he had already heard the full story from Harold, and that he was there for him and his mother. . . . He'd been brought up to be loyal to family and the people close to him."

Giuliani says he can't remember much about the episode O'Leary describes. Nor does he remember his father, who died in 1981, ever lecturing him about loyalty, only that his dad routinely exemplified the quality until it acquired the force of an ethic in the Giuliani household.

Harold, he says, once offered him an important bit of advice. "He said to me, 'It's more important to go to a funeral than a wedding, because people are going to need you more at a funeral,' " Giuliani recalls. "He said you have to be there for people who are there for you even remotely. . . . That was about loyalty for him. . . . In my upbringing, I grew up seeing that."

But there were limits in 1961 to what Giuliani knew about his father's past, particularly the extent of his allegiance to relatives. A year earlier, Harold had asked O'Leary for a favor: Would he speak to a judge on behalf of one of his nephews from his wife Helen's side of the family, a young man who had yet to be sentenced for trying to sell a stolen car?

Twenty years later, during his first campaign to become mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani would tell O'Leary that he never knew that his late father and O'Leary had interceded on behalf of his lawbreaking cousin. "I don't want to know any more," O'Leary recalls a protesting Rudy saying as he began telling the story.

O'Leary says he did visit the judge, who told him that he'd already decided not to lock up Rudy's cousin. "The judge said to me that he didn't think the kid had a chance growing up under the circumstances he did," O'Leary remembers.

Helen D'Avanzo Giuliani's side of the family included men with links to organized crime. Rudy's troubled cousin, Lewis D'Avanzo, had grown up in Brooklyn, not far from where Harold Giuliani had lived and worked for Lewis's father, Leo D'Avanzo, a Mafia-connected bar owner who was a bookie and a loan shark on the side. Harold tended the bar and sometimes collected debts. Having considered a career as a boxer, he was good with his fists, an ideal enforcer.

It was not Harold's introduction to trouble. In the early 1930s, a decade before Rudy was born, he robbed a New York milkman, a crime for which he spent about a year in Sing Sing prison -- another episode in Harold's life that his son would later say he knew nothing about until he read Wayne Barrett's 2000 biography, "Rudy!"

Long after Harold's release from prison, his associations with some of his Brooklyn in-laws meant that trouble continued to lurk. But, after his enforcer-bartender period, Harold decided to change his life and get his young son away from the influence of criminal family members, O'Leary says.

* * *

Harold rebuilt his life on Long Island, eventually landing a full-time job during Rudy's teenage years as a custodian and groundskeeper at a public high school. He bought a house in a working-class neighborhood of North Bellmore, where homes generally went for about $20,000. The couple who lived across the street, Ray and Carole Jacobelli, admired Harold as a good neighbor and a devoted family man intent on guiding his son. "In every conversation I ever had with Harold, it was always 'Rudy, Rudy, Rudy,' " Ray Jacobelli says.

Rudy won a scholarship to Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School in Brooklyn, where the student body was made up of Catholic children of Italian, Irish, German and Polish immigrants -- all of whom attended tuition-free, and the smartest of whom, like Giuliani, had been tapped from parish elementary schools in a competitive process. Giuliani rode a train and the subway for an hour each morning to get to the school, where, during sophomore year, he took his place in Room 411.

He sat in the front row, with a tan crucifix hanging directly in front of his eyes, and talked and talked. His gabbiness during homeroom irked his teacher, Jack O'Leary, known then as Brother Kevin. After several warnings, O'Leary says, he slapped Giuliani across the head. "He didn't really say anything after I did it," O'Leary remembers. "He just gathered himself and became quiet and moved on to his work. He was good after that."

The next fall, at a parents' open house, Harold and Helen Giuliani thanked O'Leary for what he'd done, noting that Rudy's grades had improved markedly after the slap. Harold invited him to dinner at the Giuliani home, the first of several Sunday dinners there for O'Leary over the next two years. "I think Harold was pulling me into their circle for Rudy's sake," O'Leary says. "I think he was sending a message to his son: 'Here's a member of a religious order. Do it his way.' Not that he necessarily wanted Rudy to go into a vocation, but he wanted him to live the right way. . . . I guess Harold saw me as kind of a confessor."

Eventually, Harold told O'Leary that he had made a serious mistake many years earlier and that he had paid for it. "I knew in context what Harold was saying," O'Leary recalls. "He'd committed a crime and gone to jail for it. He was proud he'd rebuilt his life."

Harold had found a measure of redemption by protecting Rudy from a dysfunctional family dynamic that he feared might threaten his son's well-being. But in the midst of Harold's emotional breakdown, it was his son's turn to be protective. Standing resolutely by his father, Rudy Giuliani went off as a commuting student to suburban Manhattan College and returned in the evenings to North Bellmore to be with his parents. He kept his father's problems a secret from one of his closest friends, Peter Powers, a Bishop Loughlin classmate who went on to Manhattan with him and would one day run Giuliani's mayoral campaigns and become his first deputy mayor. "I never knew about it at the time," Powers said of Harold Giuliani's arrest. "I don't think I would have mentioned something like that to a friend, either."

Then, as now, Powers and Giuliani were "like brothers separated at birth," Powers says. Their circle included another bright, ambitious Bishop Loughlin classmate, Alan Placa, who sometimes double-dated with Giuliani. Placa pledged the same fraternity at Manhattan as Giuliani and Powers did, and became editor in chief of the student newspaper. Giuliani was a liberal columnist for the paper and a passionate fan of John F. Kennedy.

The three friends would go on to New York University Law School, after which Placa would become a Catholic priest. The men's devotion to one another has remained absolute in the four decades since. Placa helped Giuliani secure a church annulment of his first marriage, officiated at his second marriage, baptized both of his children and presided over the funeral of Giuliani's mother in 2002. During his mayoral years, Giuliani invited Placa to join his staff at Gracie Mansion, but Placa declined.

After Giuliani left office, Placa's New York diocese suspended him from the priesthood after child molestation allegations. Giuliani, who by then had established a security consulting firm, came to his old friend's rescue. He hired Placa at Giuliani Partners and has remained his steadfast benefactor and defender ever since, even as detractors demand that he explain his close relationship with, as one child abuse activist has put it, "a credibly accused child molester."

The Placa friendship has been a delicate matter for the Giuliani campaign. But Giuliani, given the anguish of his father's restroom incident, has long harbored skepticism about morals charges, O'Leary says. And Placa never has been charged. "I've known Alan for 50 years," Giuliani says. "I know the wonderful person he is. . . . So of course I'm going to give him the benefit of the doubt. He said he didn't do this. I believe him."

It is the same personal allegiance that helped Bernard Kerik, Giuliani's former driver, rise to become the commissioner of the New York Police Department and a partner at Giuliani's security consulting business. In 2004, Giuliani recommended to the Bush administration that Kerik be appointed homeland security secretary. Even after embarrassing disclosures about his private life torpedoed Kerik's chances for the position, Giuliani was slow to distance himself. Only later, after Kerik pleaded guilty to corruption charges in New York, did Giuliani finally cut ties. "Rudy probably did that a little late," says Ray Jacobelli. "He and his dad believed in sticking by people to the end."

What Giuliani expected in return was absolute loyalty and, perhaps, fealty. If there has been a constant in Giuliani's relationships since childhood, it is that he has always been the one in control -- at least if the relationships were to endure. His friends and acolytes have been mocked as "YesRudys." His longest-lasting alliances have always been with men content to labor in his shadow. Those who haven't, such as his former police commissioner William J. Bratton, generally don't last long.

* * *

No one in his personal circle has ever outshined or upstaged Giuliani. His fraternity brothers immediately saw a young college man with an ambition to be in charge of others. "He was a leader, not somebody's follower," remembers fraternity brother Gene Hart. "Rudy would have been the first to say that he couldn't have done what he did later without somebody like Peter Powers there for him -- but Rudy was the leader. . . . He had to be."

Harold Giuliani, recognizing his son's talents and ambition, tried to help him stand out at Manhattan College. Having long since snapped out of his deep depression and returned to work at his brother-in-law's bar, Harold picked up the phone one day and called Rudy's rival in an upcoming election for the presidency of the Phi Rho Pi fraternity.

"His father asked me to withdraw my name from the election," Sal Scarpato remembers. "He said Rudy would be able to benefit more than I would from being fraternity president -- because Rudy was going places. It was a short conversation. I just said, 'No, sir.' " Giuliani won the election.

The next fall, he was leading a fraternity meeting in a classroom when Scarpato, objecting to Giuliani's refusal to let him introduce a new topic for discussion, exploded. "I don't even remember anymore what I wanted to talk about -- probably having a party or something," he explains. "Rudy didn't like interference. He'd instituted Robert's Rules of Orders, and he blocked me from bringing anything up. I was frustrated. I threw a glass bottle of 7-Up, and it cracked the blackboard in the classroom."

Giuliani and Scarpato exchanged heated words and challenged each other to fight. Accompanied by other fraternity members, they took a short walk down a hill to Van Cortlandt Park, where a brief clash ensued. Many years earlier, Harold Giuliani had taught his son how to fight. Scarpato never stood a chance.

"I just remember a few blows, and I remember that at some point he had me on the ground," Scarpato says. "He said, 'Say uncle,' and I said, 'Yeah, I give up.' Then we shook hands, walked back up the hill and resumed the meeting."

Over time, Scarpato acquired a grudging respect for Giuliani, and later a deep admiration. "The way he used Robert's Rules of Orders -- it was clever," remembers Scarpato, a Giuliani campaign contributor who now lives in Westlake Village, Calif. "He was young, but he knew that whoever controlled the agenda of something controlled everything. . . . He was already thinking about serious things. I remember him saying he was going to go after the mob someday. He said that he had been exposed to problems that people had in running a bar in Brooklyn and that he would go into government and go after the mob. He had a plan."

Like most of his fraternity brothers, Giuliani was a passionate Democrat through early adulthood. He served as a state Democratic Party committeeman in his early 20s and voted for George McGovern in the 1972 presidential race. But his politics changed dramatically in the 1980s while he served in the Reagan administration as an assistant attorney general. During his emergence as a mob-busting U.S. attorney, he became a registered Republican.

"We had a lot in common in those days when he voted for McGovern," remembers Jack Loiello, a Giuliani classmate at Bishop Loughlin who served in the Carter and Clinton administrations. "Years later, we went different ways politically. I'll be supporting a Democrat for president, but even so, I think Rudy would be a good president, I really do. I like how he's always remembered his friends. . . . Look, he's stuck with Placa. I think you have to admire that."

* * *

It is Giuliani's often tense relationship with his adult children, Andrew and Caroline Giuliani, that mystifies his old friends and classmates. Though most won't discuss it publicly, their voices betray an ache when they talk about the subject for long.

Giuliani says he loves his children: "There are times when there have been big disagreements. There were times in my own relationship with my father when we argued. Relationships between parents and children go through all different phases, and I think it comes out the right way in the end." He pauses, and mentions a mutual respect and devotion that, he believes, are still there with his children. "As we get past the hurts and grievances, I think we will realize all that."

Still, longtime friends worry about the possible impact of those strains, as well as Giuliani's three marriages, on his presidential bid. And they question how Giuliani, so tightly bound to Harold and Helen Giuliani, could find himself in such a position.

Only his old neighbor and die-hard defender Ray Jacobelli has dared to offer a theory. "I was there when he became mayor," Jacobelli says. "I remember Andrew having fun at his inauguration, goofing around, and Rudy loving every minute of it. Those were good days for all of 'em. But maybe after that Rudy was too busy to be a father. . . . That was different than what Rudy had as a kid. Harold had time for him. Harold was there every second. . . . He was the most important and loyal person ever in Rudy's life. He is why Rudy is what he is."

Jack O'Leary can still see Harold Giuliani in the back yard on that spring day, looking up at his son with misery, guilt, hope. "He was going to be there for Rudy until the end. I think Rudy took that with him."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.