By Susan Ager

The Detroit Free Press

January 27, 2008

http://www.freep.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080127/COL02/801270521/0/ENT03

Tony Cureton is 63 years old, the divorced father of two young women he raised alone. He is a grandfather, too.

He nursed until her death a woman he calls "my beloved in Christ," and still wears the ring she would have given him on their wedding day.

He has been a Girl Scout leader, a cop, a teacher and a monk.

Now, he is a new priest of the Roman Catholic Church, a latecomer to a vocation young men are spurning.

He lives with his frail mother in the former convent of Our Lady of the Lake parish in Prudenville, on the shores of Houghton Lake. Theirs are the only black faces he's seen in this town of 1,700 people, which swells each summer with cottagers.

|

| Father Tony Cureton prays before mass with second-grader Jack Wybraniec at his new parish in Prudenville. Father Tony was among the oldest in his seminary class. Photo by Larry Coppard |

But oh is he welcome. "Fervor," says Gary Miesel, lay leader of the parish council. "That's the word for him."

Ordained at 60, Father Tony is perhaps emblematic of the future of the Catholic priesthood. He comes to it with plenty of mistakes and lessons under his belt. He brings to it the enthusiasm of a newcomer and the wisdom of a mature man -- torn, patched and restitched, like a child's favorite stuffed animal.

"I've learned one thing," he tells anyone who asks. "It's a lot more work being a pastor than a single parent. This family is a lot bigger."

A winding path

|

| Father Tony's family joined him for his ordination three years ago. Front row: His mother, Savannah; second row: granddaughter Ebony and grandson Ray; third row: daughter Carrie, Father Tony, daughter Dawn and Bishop Patrick Cooney. |

Although he dreamed of being a priest as a boy, Tony Cureton (CURE-ton) says he spent most of his life running from a real relationship with Jesus.

His parents divorced when he was 3. His mother enrolled him at 6 in a Catholic school in Indianapolis, upon a friend's advice, and he took to the priests as surrogate fathers. They paid special attention to him, he says, because with ADHD (only recently diagnosed) he was curious and thoughtful, but fidgety and distractible.

Raised a Southern Baptist, his mother converted to Catholicism, telling her son, "I know you'll come home from school with questions."

|

| Father Tony says he hopes he has another decade or more to redeem his earlier life, to re-energize his new parish and to make its children laugh. Photo by Larry Coppard |

Businessmen in the parish paid to send him to a high school seminary in the Catskill Mountains of New York. Five years later, he said, "the world got ahold of me and I got ahold of the world."

He dropped out of the seminary and worked for a time as a cop in Ft. Wayne, delivering a baby boy in the back of a cop car, and using his gun just once, to kill a dog about to attack his partner.

At 22 he married his pregnant girlfriend. It was a marriage that lasted just three years. He took full custody of his two young daughters and moved to California to start a new life near his grandmother and in a state where, at the time, college tuition was free.

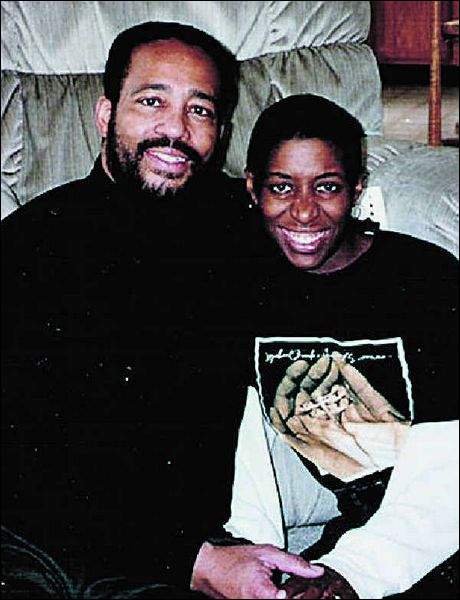

|

| Brandie Atwine died just months after she and Tony Cureton were engaged. "It was the only spiritual relationship, God-centered, that I ever had," he says. |

Working full-time, parenting full-time and studying full-time cast him at times into despair, but during one funk he realized a comforting truth he repeats to himself even today: "Life is a school."

Always a thinker -- "sleep is a necessary evil" -- Tony cast about for a spiritual grounding, studying metaphysics and even working with a guru.

Dropping in and out of school, he finally got a bachelor's degree in psychology and began teaching in Los Angeles public schools, mostly fourth- and fifth-graders.

|

| Father Tony still wears the gold ring his fiance would have given him on their wedding day. Photo by Larry Coppard |

He loved that work, he says now, "because it's easiest to see Jesus in the eyes of a child."

During a train trip around the U.S., he returned to the Catskills and the seminary of his youth. "The chapel drew me like a magnet," he recalls. On his knees at the altar, he wept with a sense of homecoming and felt a stirring he can only describe as a longing for "more," for a way to serve God, again.

A bittersweet love story

"Bless me, Father, for I have sinned," he told a priest a few weeks later. "It has been 30 years since my last confession."

Back home, he began attending St. Brigid Catholic Church in south-central L.A., a 44-mile round-trip drive from his home in Long Beach. He chose it because it was rousing, almost Baptist, with masses that lasted two hours, more than twice the usual.

There he met Brandie Antwine, whose eyes, he says, "shone with a love of God" that dazzled him.

She warned him on their first date that she had a rare lung cancer that was likely to return. Six months later she agreed to marry him and he began working on getting an annulment for his early marriage, a process the Catholic Church requires if one is to be married in the church again.

But the cancer rose up, killing her eight months later at age 31. She died in a hospital bed in the living room of his apartment.

"I never knew it was possible for anybody to hurt so much and still be alive," he says. "Even though we were not officially married, I consider her my beloved in Christ. It was the only spiritual relationship, God-centered, that I ever had."

Within a couple years after her death in 1994, encouraged by the pastor at St. Brigid, he left teaching to join a Cistercian monastery in Wisconsin, near his oldest daughter. He took the name Brother Augustine, after the saint who lived a hedonistic life for many years before turning to Christ.

There, in the company of four longtime monks and a handful of acolytes like him, he rose each morning at 4 for early prayers, cleaned house, maintained the monastery's aging fleet of cars, scheduled visitors and prayed, always prayed, surviving on five hours of sleep each night, pushing always to stay awake and alert as late as he could.

But he felt restless. Contemplation comforted him, as it always had, but he felt called to a more active life in the world and his superior at the abbey agreed.

He was, however, 55 years old. He needed a diocese to sponsor him, in effect to pay his way through four or five years of seminary, at a cost of close to $100,000.

"Mention your age last," one priest told him. He did. But a half dozen dioceses still rejected him. One bishop, he learned, turned him away because he was divorced.

He was finally accepted by a diocese in Gaylord, in northern Michigan -- and studied at the Sacred Heart School of Theology, near Milwaukee. It's the largest seminary for second-career vocations in the country, with 108 men whose age averages 45.

Tony was among the oldest.

The Rev. Tom Knoebel, director of recruitment at Sacred Heart, promotes older priests as men who've "been humbled by life, who know that bad things do happen to good people."

But he recognized the reservations some dioceses have. Older priests are perceived as stuck in their ways, uneasy about administrative tasks or sullied by past mistakes.

"Some people think if you couldn't remain faithful to one vocation, why should I think you could remain faithful to a second?" Father Tom says.

Instead, he says, most Catholics forgive mistakes and don't expect their priests to have been saints.

Still, a lay woman from the Gaylord diocese warned Tony: "Some people up here won't like you."

He thought, "So what's new?"

His three years in northern Michigan have been without incident, first at a parish in Cheboygan, then Petoskey and finally Prudenville.

"When somebody gives me the look," he says, "and you know the look, I give them a big smile" -- he demonstrates, then shouts "HELLO!"

"That," he says, "startles them out of their stereotypes."

A warm welcome

At Our Lady of the Lake, parishioners are deeply grateful for him.

The parish was without a resident priest for nine months. Its previous priest, a widower who became a priest in middle age, left after just three months to get married.

The Prudenville parish is one of three in a cluster, administered by a pastor who lives a half hour away. Father Tony, called an associate pastor, is the daily presence, working dawn to dark.

Longtime parishioner Barbara Stovall, 67, says of Father Tony, "We love him. He's a sweetheart, very easy to talk to" compared, she says, to "some priests who act as if they could care less."

Gary Miesel, of the parish council, says most priests of Father Tony's age "are burning out, while he's just starting. He's wonderful, dynamic, and his homilies are fantastic, just inspired."

Father Tony has no training on stage, but admits to being a ham, telling stories from the altar, raising and lowering his voice to command attention and moving his body like a dancer.

One of his mentors, the pastor of a parish in Petoskey where he served for 18 months, says Father Tony's life is his biggest asset.

"He is able to speak to people in a different way than I ever could," says Father Dennis Stilwell, who was ordained 36 years ago when he was 27. "He's been there, where they are: in marriage, in a bad marriage, as a single parent. He can tell stories in his homilies that I can't tell.

"He has a special ability to connect."

What's ahead

Although diocesan priests like him aren't bound by vows of poverty, Father Tony owns very little beyond his car and his clothes. His prized possession is a black office chair. He gave away his furniture when he left California for the monastery.

He also cashed out his teachers' retirement fund, split most of it between his daughters and kept for himself just $1,000, some of which paid off in the stock market.

"They say God helps those who help themselves," he says. "They also say God takes care of babies and fools. Whatever, I'm mostly concerned about my mother," who is 87 and has suffered for decades from a painful chronic disease. He got permission for her to live with him before he moved to Prudenville last summer.

He hopes he has another decade or more to redeem his earlier life, to re-energize the parish, to engage the children, to make them laugh. Teaching forgiveness at one recent mass for the parish school's 62 students, he called a boy up front, took the child's arm and, landing a fake punch on his own face, shouted, "Pow!"

"Do I hit him back or do I forgive him?" he asked as the boy stood with eyes wide. "Forgive him!" the children called out.

Earlier a second-grade boy lay on a green cotton blanket on the altar while four other kids lifted the corners to demonstrate how a paralyzed man was carried by his friends to see Jesus.

"Poor Jack!" Father Tony joked about the boy in the blanket, waving his arms until all the children repeated, "Poor Jack!"

Amazed by the demands of the job, he wishes he could find time to take pictures, a long-time hobby. He wishes he could organize his desk, which he refused to show us. He lets himself play an online computer game called "Starlancer" only when he's caught up; he hasn't played in three years.

And, he wants to lose weight. In the church bulletin, in his first letter to the parish, he pledged to "lose a minimum of five pounds a month." He asked them to say something "if you see me with a cookie or doughnut in my hand."

He drinks protein shakes, the same ones he doctors with honey for his mother. A treat is scrambled eggs and bacon.

But has he met his goal?

"My pants," he concedes, "seem to fit the same."

What comfort: He's only human.

Contact SUSAN AGER at 313-222-6862 or sager@freepress.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.