By Brian T. Olszewski

Catholic Herald

May 14, 2009

http://www.chnonline.org/main.asp?SectionID=14&SubSectionID=13&ArticleID=1488

ST. FRANCIS - Whether the distance between knowing about someone and knowing someone is a chasm or a few, short steps, the autobiography can serve as the bridge from knowing about to knowing.

That might be what Catholics in southeastern Wisconsin find should they read "A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop" by Archbishop Emeritus Rembert G. Weakland.

Your Catholic Herald obtained a draft copy of the book. In person and in writing, your Herald has extended two invitations to Archbishop Weakland: One is to be interviewed about the book and about his move from Milwaukee to St. Mary's Abbey in Morristown, N.J. next month; the other is for him to write a first-person piece. As of May 12, he had not responded to either invitation.

Why he wrote it

|

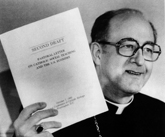

| In 1981, Archbishop John R. Roach asked Archbishop Rembert G. Weakland to chair the U.S. bishops’ committee charged with drafting the pastoral letter on the economy. Archbishop Weakland is pictured with the second draft of the letter in 1985. The third draft, titled “Economic Justice for All: Catholic Social Teaching and the U.S. Economy,” was overwhelmingly approved by the bishops in November 1986. Photo by CNS |

In the 384-page book, set to be released by Eerdmans Publishing May 29, Archbishop Weakland, 82, details aspects of his life from birth to retirement. In the prologue he explains why he wrote it:

"I write because I am internally propelled to share with those I love and served for so many years a fuller story than I was able to tell in May 2002 when I apologized publicly to them. Most of all, this need is rooted in a religious motivation. It is embedded in my concept of the Church's nature and as a communion of believers on a faith journey, a communion of saints (few in number) and of sinners (most of us). My story affects everyone else's story and thus, at least in part, belongs to them."

In the epilogue, he returns to why he has written his memoirs, adding that he "often had a front seat" in the church and world history that parallels his life. Noting concern about "revisionism" he detected particularly when people were writing about the years of Pope Paul VI's pontificate, the archbishop wrote, "I have thought it important to say how I, as one individual, saw what was happening then. True, it is only one believer's experience, but, I hope, one worth sharing and saving for posterity."

Roots of a vocation

The story wends from his childhood and Benedictine vocation in western Pennsylvania to his rise to the leadership of the Benedictines. At age 36, he was elected archabbot for life of St. Vincent Abbey. While he was ascending in the community, the Second Vatican Council was underway. He recalls his enthusiasm for Pope John XXIII's opening talk and writes, "Can anyone fault those of us who expected the council to usher in a new era for the Church as it looked at its heritage, tried to renew and update itself, and then contribute to a better world?"

Archbishop Weakland adds that during the council he changed his "image of God from that of enforcing policeman to one of a loving and caring parent."

The latter part of the fifth chapter and most of the sixth are devoted to the council, and to the hopes he had for its work, and what he would experience in later years.

More leadership responsibilities

In 1967, the Benedictines, while meeting in Rome, elected him the fifth abbot primate - head of the Benedictine Order. Chapters seven and eight contain detailed accounts of his visiting Benedictine communities throughout the world. During this time, he would regularly meet with Pope Paul VI, whom he describes as having "a monastic soul and sensitivity."

In chapter nine, while he writes about his role as abbot primate, Archbishop Weakland writes about his sexual awakening and orientation, at age 45, and about the ramifications of a celibate life.

"I never doubted my vocation or the significance of the vows I took; but now I had to see them in a new light, namely, not as the avoidance of sin and evil, but as a new way of living the gospel of love that Jesus Christ preached. I wanted to be a person who lived by love not fear," he writes.

In much of Chapter 10 the archbishop writes about the final years of Paul VI's pontificate and the challenges the pontiff faced inside and outside the Vatican. He also recounts his decision to accept the pope's personal request in September 1977 that he become archbishop of Milwaukee, noting how he struggled with not accepting the appointment ("I never wanted to be a bishop, otherwise I would never have become a Benedictine") and accepting it (" ... how could I refuse the personal wish of the pope and still be at peace with myself?").

Vatican, Milwaukee links

According to Archbishop Weakland, during his final meeting with Pope Paul VI, the pope told him that the best preparation for being a bishop was to have been an abbot. From 1977 to 2002, the years covered in the final five chapters of the book, he details local, national and international aspects of his being a bishop. Often, they were interwoven, e.g., a dinner for married priests and their wives in 1979 and listening sessions on abortion in 1988, and the renovation of the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in 2001-2002, were local matters that became Vatican concerns.

"On every ad limina trip without exception, I noticed that I would be singled out (the other bishops were never aware of this) and told to meet with Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio in the Congregation for Bishops (or later with his successor Cardinal Bernardin Gantin in that same congregation) and then with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith," Archbishop Weakland writes. "Upon arrival in their offices, I would be presented with a list of complaints. These were actions or decisions of mine that seemed to irritate the pope and members of the curia."

Of the future Pope Benedict XVI, the archbishop writes, he "always treated me professionally and respectfully."

Four years into his episcopacy, Archbishop Weakland was asked to chair the U.S. bishops' committee responsible for drafting the pastoral letter "Economic Justice for All." He terms the experience "one of the most important and formative periods of my life."

During the bishops' spring meeting at Collegeville, Minn. in 1988, Archbishop Weakland learned that the Congregation for Bishops had asked another U.S. archbishop to investigate him. He writes that no one from the Holy See spoke to him about the outcome of that investigation when he was at the Vatican for his ad limina visit in December 1988.

"Through it all, I retained a deep respect for the Holy Father as pope, but found little to love and admire in his style of treating people who disagreed with him," Archbishop Weakland writes. "I was convinced that he was indeed a very holy man, but not one without flaws."

Start and finish

Archbishop Weakland's prologue focuses on his apologizing to the Catholic community of southeastern Wisconsin on May 31, 2002 "for the scandal that has occurred because of my sinfulness" and with an explanation of his relationship with Paul Marcoux in 1979, the $450,000 financial settlement paid to him in 1997 with archdiocesan funds and the relationship and settlement being made public by Marcoux in 2002.

The final paragraph of the book reads:

"If I have any sadness, it is that we have made too little progress in understanding and helping victims regain a full life. Too many seem to be left in anger. I also regret that, although we have made headway in delineating the profile of the perpetrators, we have made little progress in detecting this addiction early on and then seeking some sort of cure or humane control. We all are, in that sense, victims of the times we live in and have to accept those limitations, hoping and praying that the next generation will do better than we did. For these reasons, I am at peace with my God, with my Church, and with myself."

With money he earned from speaking and writing, and through funds raised by several of his friends, Archbishop Weakland repaid the $450,000 to the archdiocese. In a recent interview with The Associated Press, the archbishop said proceeds from the sale of his memoirs will be donated to the Milwaukee-based Catholic Community Foundation.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.