By David Gibson

Politics Daily

October 4, 2009

http://www.politicsdaily.com/2009/10/04/a-catholic-court-let-the-arguments-begin/

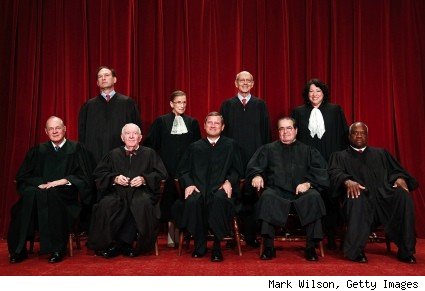

The new session of the Supreme Court of the United States opens Monday with a slate of important cases looming — and a novelty that some worry is more than a historical curiosity: namely, with the addition of the newest justice, Sonia Sotomayor, six of the nine justices on the high court are . . . Roman Catholics.

John Grisham, where are you? Do we need to call Dan Brown? Or has this issue already moved well beyond the realm of popular fiction? Some would say so.

|

The five Catholic justices that Sotomayor joins — Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Anthony Kennedy and Chief Justice John Roberts — already represented a historic high, and now Catholics will comprise two-thirds of the bench. This is well out of proportion to the 24 percent or so of the general American population that is Catholic. The question is, does it matter?

In a column penned after Sotomayor's nomination, Joyce Appleby, a distinguished historian emerita from UCLA, argued that because the Catholic Church has taken strong stands on issues such as abortion, gay marriage and the death penalty, "it raises serious questions about the freedom of Catholic justices to judge these issues." Her suggestion is that they ought to recuse themselves from such cases.

"Surely ingrained convictions exert more power on judgment than mere financial gain," Appleby wrote in the Tallahassee Democrat. "Many will counter that views on abortion, same-sex marriage, and the death penalty are profound moral commitments, not political opinions. Yet who will argue that religious beliefs and the authority of the Catholic Church will have no bearing on the justices when presented with cases touching these powerful concerns?"There are counterarguments, to be sure.

For one thing, the preponderance of Catholics on the high court today still leave Catholics underrepresented, historically speaking. All told, there have been 11 Catholic justices out of 108 in U.S. history, just 10 percent of the total. By themselves, Episcopalians and Presbyterians have accounted for 50 percent of all Supreme Court justices, even though, as of the year 2000, those two denominations accounted for less than 5 percent of the population.

Unitarians have been most overrepresented, historically; and Jewish justices now account for two of the three non-Catholic seats on the high court — a 22 percent share that is much greater than the 1.5 percent of the population that Jews would be accorded by proportion, and a higher percentage even than the current overrepresentation of Catholics.

But few are citing those disproportionate numbers today, nor were there complaints in the past about having too many mainline Protestants on the high court. And if Catholics should recuse themselves from certain cases, why was this never an issue during the 150 years when there was generally just one Catholic justice? Theoretically, the principle would have applied all the same.

Yet It seems likely that the Catholic question will continue to percolate during the coming term given the number of high-profile cases on the docket. Already, on Wednesday, the court will hear arguments in Salazar v. Buono, which will decide challenge to the presence of an eight-foot-tall cross on federal land in the Mojave National Preserve in California. The ruling by the justices is likely to have a lasting impact on the many controversial displays of religious symbols on public land around the country.

In addition, cases regarding the regulation of executive compensation, the constitutionality of life sentences for juvenile offenders, and parental custody statutes will all reveal something about the beliefs and temperaments of the various justices. Add to that the fact that John Roberts is expected to start shaping the court even more vigorously as he enters his fifth year as chief justice, and Samuel Alito is also expected to begin putting his stamp on decisions; both men are conservative Catholics, and Alito replaced the more moderate Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman to serve on the high court. (Sotomayor is only the third — talk about underrepresentation!)

But it is the numerical weight of Catholics that seems to spark the concern. In 2007, when all five Catholic justices voted in a 5-4 decision in Gonzales v. Carhart to uphold the constitutionality of a federal ban on late-term, or so-called partial-birth, abortions, University of Chicago Law School Professor Geoffrey Stone wrote a blog post, "Our Faith-Based Justices," arguing not only that the majority was dead wrong, but pinning the reason on their religion:

"Here is a painfully awkward observation: All five justices in the majority in Gonzales are Catholic. The four justices who are either Protestant or Jewish all voted in accord with settled precedent. It is mortifying to have to point this out. But it is too obvious, and too telling, to ignore. Ultimately, the five justices in the majority all fell back on a common argument to justify their position. There is, they say, a compelling moral reason for the result in Gonzales."And that morality, Stone argued, was based on their sectarian Catholic views. (Cartoonist Tony Auth also sparked controversy with a caricature of the five Catholic justices wearing bishops' miters.) In the wake of Sotomayor's confirmation, Stone reprised his views in a Huffington Post essay, noting that his longtime friend Scalia had objected strongly to Stone's arguments. But Stone persisted, and tried to bolster his thesis while at the end admitting "none of this necessarily 'proves' anything."

Scalia would no doubt agree with that last statement. He has for years protested that his faith has no impact on his decisions, nor should it:

"There is no such thing as a 'Catholic judge,' " Scalia said in a 2007 speech. "The bottom line is that the Catholic faith seems to me to have little effect on my work as a judge. . . . Just as there is no 'Catholic' way to cook a hamburger, I am hard-pressed to tell you of a single opinion of mine that would have come out differently if I were not Catholic."In 2002, Scalia went so far as to argue that any Catholic judge who opposed the death penalty because they believed it to be immoral "would have to resign. . . . You couldn't function as a judge." Scalia speaks, as do Clarence Thomas and, to a certain extent, the other conservative Catholics on the bench, from the point of view of an "originalist," or one who argues that justices must decide cases only according to the original intent of the framers of the Constitution. (Originalism is an updated — and some argue improved — version of "strict constructionalism.") Divining the original intent can itself be a matter of debate, so some argue it is unrealistic to say there is a fixed and correct answer to every case that judges can call like an umpire.

Cast in the opposing role is the concept of the "living Constitution,"— that is, the view of the Constitution as a dynamic document that must be interpreted to meet evolving standards and new developments (such as what constitutes "cruel and unusual punishment," or when something is obscene, or whether racial segregation is illegal or abortion legal).

This debate does have a clear "religious" parallel in that it underscores a common dynamic at play in both American jurisprudence and Roman Catholicism (as well as other faiths) — that is, whether or how much the Constitution, in the first instance, and religious doctrine, in the second, can or should change.

Arguments over whether churches should ordain openly gay clergy or permit same-sex marriage seem open-and-shut cases (in the negative) to religious "originalists," while those who embrace the notion of the "development of doctrine" note that Christianity has changed its teachings on slavery, usury, capital punishment, religious freedom and, in some cases, the ordination of women.

Some Catholics might take one side (Scalia, e.g.) while others (perhaps Sotomayor) would have another view. In other words, there are Catholics and there are Catholics. How else to explain this coincidence: On April 16, 2008, the day Pope Benedict XVI arrived for a historic visit to the United States, during which he would repeat the church's opposition to capital punishment, the Supreme Court upheld the lethal injection method of execution and all five Catholic justices combined to back a decision that goes against Catholic teaching.

This division between enforcing established principles and applying developing doctrine was at the heart of the "empathy" debate swirling around Sotomayor's nomination, and the propriety of her remarks that her experience as a "wise Latina woman" would lead her to reach different conclusions on cases than other justices. President Obama has also said he wanted to nominate justices with "empathy," who would understand the plight of the little guy in court cases.

The "empathy argument" outraged many conservatives, who tend — like Scalia et al. — to be originalists who would oppose the "activism" that such feelings could lead to. Ironically, some conservatives are uneasy about justices checking their beliefs at the door, as that could lead to an affirmation of, for example, gay marriage as a matter of constitutionally protected equal protection rather than something barred by longstanding social custom and religious belief.

In First Things, a conservative journal, Joe Carter argued recently that everyone has religious beliefs that influence their views, and so sectarian believers — like Catholic Supreme Court justices — should not retreat from invoking those specific beliefs. Otherwise, he wrote, "the result is that certain religious beliefs (e.g., those that are reductionist and based on materialism) are welcomed while others (any religion that relies both on general and special revelation) are excluded."

In the end, the arguments from both sides as to whether the court is too Catholic, or the justices too strict in their rulings, or too empathetic, come down to where one stands politically, and where different people want to court to go, politically. That can include justices. And beyond the relatively few easy calls, the Constitution is what the justices say it is.

That explanation doesn't satisfy everyone, however.

On Sunday morning, in fact, at the Catholic cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington, hundreds of lawyers and judges and politicians gathered for an annual rite called the "Red Mass," a service held on the Sunday before the opening of the Supreme Court session to invoke "God's blessings and guidance in the administration of justice under the power of the Holy Spirit."

Last year at this time, Marci Hamilton, a legal scholar at Yeshiva University's law school and a lawyer who represents victims of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy, pointed up not only questions of "propriety" about the attendance of six Supreme Curt justices at the Red Mass (five Catholics and Justice Breyer, who is Jewish — go figure) but also about the none-too-subtle influence the rituals could have on their minds, and ours. "The Red Mass is a public affair intended to reinforce the ties between government and the Church," she wrote.

Alas, it was hard to figure out what was behind this year's agenda. Five Catholic justices were there, including Sotomayor. But Clarence Thomas was not. And Breyer came again! Vice President Biden was there, to boot, along with two Cabinet secretaries and hundreds of legal professionals. But in his homily at the Mass, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, the newest U.S. cardinal, preached about the scriptural example of adding "a tone of sympathetic understanding and a message of consolation" to legalistic pronouncements, and the duty to work for a "reversal of injustice and a merciful uplifting of the poor and those of no account."

Formal, specialized legal knowledge, the cardinal said, "frequently becomes semi-mechanical and distancing."

"A person can forget that the basis of that knowledge is something much more natural in the human condition, that the law and lawyers are around because justice among human beings is always an issue. There are always smoldering wicks and bruised reeds needing our human attention, an attention that cries out and says that even sophisticated, knowledgeable 'human' lawyers need reminding, need a purifying divine fire from the Lord, both in their personal lives and in their profession itself."That sounds suspiciously close to empathy. Maybe Sotomayor is the Catholic everyone should be worried about.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.