Care Leavers Australia Network

November 15, 2009

http://www.clan.org.au/news_details.php?newsID=276

AUSTRALIA -- There will be no official order of events at this quiet reunion at the Riverview Training Farm for Boys, though speeches should start soon after the browning of Wally McLeod's much-vaunted barbecue sausages. What matters is being here: making the turn off Ipswich Motorway, reaching the end of Endeavour Street, even when your stomach wants out; passing through the gates and trudging up that sorry driveway to stand in the places that haunt your dreams: the laundry, the lucerne field, the piggery, the shower block.

|

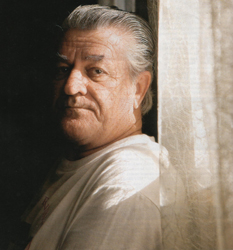

| Facing Fears... Former Riverview boy Bob Toreaux in the room where the 'punishment parades' took place. |

There's a reason the semi-circle of 50 plastic chairs Bob Toreaux has set up face the entrance to the farm's recreation hall. It's the hall he sees in the recurring dream he has of a 12-year-old boy, naked from the waist down and straddling a wooden vaulting horse, blood running down his legs. It's the hall they all see in their sleep.

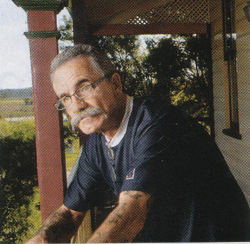

"Hey Bob, look who's 'ere," calls McLeod. A man with a bushy moustache and tattoos pads warily up to the group gathered around a barbecue outside the hall. Trevor Swifte spent nine months at the farm at Riverview, a suburb ten minutes north of the Ipswich CBD, in 1973. Some of these men spent nine years here, and still they tilt their heads to Swifte. "Aw, mate," says Toreaux, close to tears. "Didn't expect to see you here." Swifte smiles under his moustache: "Didn't expect to see me here, either." Toreaux pats his shoulders warmly with both hands. It's as close to a hug as one can expect from a "homie", the loose term for those who did time in one of Australia's 500 state-run homes and orphanages.

McLeod turns his sausages and jokes with Toreaux. "Beats eatin' weevils, hey Bob," he says. A handful of men go to enter the hall, like boys climbing stairs to a ghost house. McLeod's face is grim. He gives the men a nod, eyebrows raised, that suggests fortune favours the brave.

Inside, Philip Morris, last here as late as 1974, stands with a cap pulled down hard so the tops of his ears fold over. His fingers clench his thumbs. He rocks nervously, shifting his weight, staring at a blue and gold banner that says "By Grace Are Ye Saved Through Faith". Most of the men approach the Salvation Army's honour rolls, three timber boards celebrating the officers who served here between 1893 and March 1976, when the home was finally closed after being damaged by the 1974 flood. Some of those officers' names are muttered; officers entrusted under God, some paid by parents or the state, to rebuild the lives of boys not blessed by family, money, education and love – leftovers of the Depression and war, sons of damaged fathers and penniless mothers.

Brian Hanrahan, 69, was sent here as an 11- year-old ward of the state after stealing a set of keys from the Roma Street rail yards. It was Christmas. He was sentenced to remain on the farm until he was 18. "From then on I was Number 14," he says. He rests on a bench that runs the length of the hall, takes a deep breath.

"This was beating time in here," he says. This was the place for "punishment parades". Boys were sat along the bench and ordered to watch another being struck with a cane between 18 and 24 times as he straddled a vaulting horse in the centre of the hall. Blood running from a child's buttocks and testicles was warning for all who would dare to lie, or sneak a potato from the vegetable truck, or drink from the tap without using a cup. Hanrahan inspects an honour board, running his finger over a name written in gold. "I put in to have that name taken off the honour board," he says. "He should be dug from his grave and officially prosecuted."

He looks out a window across the fields. "Some kids would wet their beds. There used to be a shower block and a laundry down there – and while the rest of us were having breakfast he'd make these kids wash out their sheets. They'd have a cold shower. And he'd sodomise them.

"Another kid and I, we went to all the bed wetters and we questioned them, and without exception, he was banging all the bed wetters. There was eight of them. Another kid and me went over to Major Chambers's quarters … " He points to a small house across the field. "We blew the whistle on [the officer]." Hanrahan chuckles, shaking his head. "They left him here for eight more years."

Men drift in the corners of the hall. One with a walking frame puts his head down, grief-stricken. Philip Morris, 50, sits by the tea cart.

"Feels like a funeral, doesn't it?" he says. From a backpack he pulls a small photograph taken in the early 1970s: it's of a handsome, wholesome looking officer sipping a drink on a bench outside the hall. This man would lure Morris into his quarters at night with promises of Milo.

After the boy fought off his sexual advances, "he'd single me out. He'd get my fingers and he'd squash them down". Morris pushes the tips of his fingers inwards at the top knuckle until his fingers are white. It's hard to say if it's pain, or the memory of it, that brings tears to his eyes. "I've come from north of Cooktown," he says. "It was a five-hour drive to Cairns and a two-hour flight to Brisbane. Cost me $1000. But I had to come. I've kept this bottled up inside me for too long."

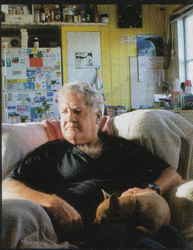

In a kitchen off the hall, Cliff Muir, 72, slices a slab of meat into steaks. He buzzes around the kitchen, a bony, hunched dynamo. "Mate, we're all good workers," he says. Muir's back never recovered from lifting large bags of feed when he was a thin pre-teen. Boys aged eight to 18 worked the farm from 4.30am until 7pm, wearing the same ratty shirt, shorts and sandshoes in the coldest winters, burying barrows of effluent, ploughing fields, feeding pigs. Few were ever paid. Presents were granted on Christmas Day and taken away on Boxing Day. In the dairy was a sign: "No talking while milking". Talkers were flogged with a stockwhip. Only recently, since his doctor told him to keep sleeping pills in his cabinet, has Wally McLeod stopped waking in the night to the cracking of a stockwhip. In 1972, aged 25, he tried to kill himself.

|

| Block Out... McLeod says his nightmares have eased off since he was prescribed sleeping pills |

Sometimes in the lucerne field an officer would find a boy working alone. In blazing heat, he'd suggest stripping naked for a cooling hose down. Tougher boys could fend off an advance with a sharp elbow. The weaker boys couldn't, and some grew into strong young men who raped weak young boys in the shower block.

Before the reunion, Cliff Muir sat with Qweekend in the kitchen of his ramshackle home in Bundamba, outside Ipswich. He smoked cigarettes and ate a meat pie with Worcestershire sauce as his daughter, Michelle Lewis, sat opposite. His wife, Bev, passed away a little over two years ago. "We never knew about all this until six months ago," Michelle said. "I always knew there was something troubling him … He was very closed, very angry, depressed."

"I'd be at a party, really happy and all of a sudden it would click," Muir said. "I'd just turn off. Bev quizzed me a lot, but I wouldn't say. I was ashamed of it. Now I'm sorry I didn't tell her. Bev used to ask me why I never gave her cuddles when I said goodbye. I never did. Us homies aren't good with affection like that." Michelle dug out a grainy photograph of a row of Riverview boys. Muir couldn't say which was him because he doesn't know what he looked like as a child. They weren't allowed mirrors. "Get Dad's photo will ya, darl," Muir asked his daughter. Then he wept softly, hands masking his eyes, thinking about the time an officer approached him in 1947 "in a little dark area of the locker room".

"Muir!" the officer barked, "You haven't written to your father." Muir said he didn't know how to compose a letter and that, in three years, he hadn't come across anything resembling letter paper. "Well," said the officer, expressionless, "your father passed away." Then he turned and walked away. Muir's mother had died in 1944. He knew then, in that dark locker room, aged 11, that he was utterly alone in the world. "That officer was a married man with kids of his own," Muir said, snorting tears through his nose. "I hope he died a hard death, that bastard. They could do anything to me from then on, but they could never hurt me."

Governor Leneen Forde presented the results of the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions to then minister for families, youth and community care, Anna Bligh. Forde, whose report detailed physical, sexual and emotional abuse of children in 150 orphanages and detention centres from 1911 to 1999, made 42 recommendations, including that the state "and responsible religious authorities establish principles of compensation".

The government, in collaboration with religious bodies including the Salvation Army, issued a formal apology to the victims.

Eight years later, Bligh, then Queensland deputy premier, announced that as a result of the Forde inquiry, victims would share in $100 million in compensation via the Forde Foundation. The government was criticised for taking too long to establish the fund, but Bligh said the priority had been to fix the existing child protection system.

After writing victim impact statements, successful applicants were given a $7000 payment followed by a possible secondary payment of up to $33,000 for those who suffered serious abuse or neglect. Some 10,500

Queenslanders submitted statements to the scheme. Level 2 applicants filled out forms asking them to detail their abuse. They ticked boxes marked "Loss of limbs or fingers"; "Damage to internal organs"; "Disfigurement from burns"; "Skeletal issues"; "Severe depression"; "Physical impact from sexual abuse (e.g., prolapsed bowel/bladder)".

Following the Level 1 payments, the state government's pool of redress money has shrunk to $46.7 million. The only notable monetary contribution to the Forde Foundation by the Salvation Army and other church bodies was a combined $95,000 donation in October 2001. It is clear nobody but the homies anticipated the flood of applications to the foundation. Some 5334 Queenslanders have sought the Level 2 compensation payment, claiming severe abuse.

And state Communities Minister Karen Struthers admits not everyone will be satisfied when those payments are released in the coming weeks. She has since written to the heads of 15 churches and orders – including the Anglican, Catholic and Lutheran churches, the Christian Brothers and the Salvation Army – asking them to provide more cash and services to people abused in their homes and orphanages. Salvation Army chief secretary Colonel James Condon tells Qweekend the organisation prefers to "work directly" with individuals offering "support and assistance as appropriate".

Leonie Sheedy, president and co-founder of Care Leavers Australia Network (CLAN), says the Salvation Army and others should be forced to sell assets to contribute to the fund, and adds that recognition from the federal government is critical to the healing process. The 2004 Senate report "Forgotten Australians", which detailed a "litany of emotional, physical and sexual abuse" in institutions last century, recommended a formal apology to the 500,000 children placed in more than 500 forms of care across Australia.

Two weeks ago, the federal government announced its intention to say sorry to the Forgotten Australians by the end of this year. Families Minister Jennie Macklin has promised to work with homies to design a formal apology, and the government has pledged a $300,000 funding boost to both the Alliance for Forgotten Australians and CLAN. "Let the healing begin," says Sheedy. "It will send the most powerful message to our children, our husbands and wives. It would say so much about the suffering they too endured. So they can understand why Mum's a bit depressed on Mother's Day or why Dad's depressed on his birthday. And why he can't face Christmas Day."

It's because of the courage of men like Barry M. that the homies are finally getting their formal apology. Barry was 11 when he was sent to Riverview; the abuse he describes carried on for two years, through 1958 and 1959. He needed three weeks of counselling after writing his statement, one of hundreds considered for the Forgotten Australians report.

The term "redress" suggests the setting right of what is wrong. This, for the Riverview boys, is impossible, no matter who says sorry, no matter how much money is handed out. "$7000?" says Bob Toreaux. "$33,000?" He laughs, poking his skull with his forefinger. "Is that going to get this out of my bloody brain?"

.

|

| Dark Past... Trevor Swifte, Philip Morris and Cliff Muir all suffered horrific abuse at Riverview |

|

|

Could anything compensate Wally McLeod for a life spent without female companionship because he freezes around women, incapable of having a conversation? Or enlighten the five wives Brian Hanrahan has had in his life?

John Munt, another Riverview homie, approached the Salvation Army outside of the formal redress scheme. He claims they promised him $60,000 but he got only $20,000. (Another man who was "buggered and brutalised" at a Salvation Army home in NSW told Qweekend he was given a $50,000 ex-gratia payment under the condition he never reveal it to anyone.)

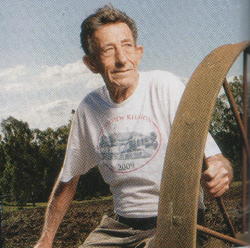

Munt, 72, walks with a cane and the dignity of a man who has fought in three theatres of war: Malaya, Borneo and Vietnam. He sits on a bench beneath an oak tree on the Riverview farm; by his side is a red cotton bag marked Queensland Carers, 30cm thick with Freedom of Information documents. He lifts the hems of his trousers.

Sickening scarlet scarring runs along his shins. "I had ulcers on my legs," he says. "[Two officers] got me and scrubbed my legs with a scrubbing brush taken from the floor of the bathroom." His legs became so infected, a doctor at Ipswich Hospital considered amputating them. He was later sent to the state run Reformatory for Boys, Westbrook, near Toowoomba – a place most homies say made Riverview look nice. "I got to Westbrook and I was so-called strip-searched," Munt says. He coughs and shifts on the bench. "I was bent over a table and I was flogged and I … " His mouth trembles, and he is lost for words. " … I had a cane shoved up my arse. They said to me, 'This is what you're here for, boy'."

He pulls the brim of his hat down to shade his face. "I've gotten so angry about all this. The redress scheme means nothing." He hands his bag over. "Please bring this to light."

Trevor Swifte is standing now on the verandah of a dormitory building, looking over to where the piggery once was. He remembers accidentally feeding the pigs corn sprayed with pesticide. A pig died. His punishment was handed down by Major Victor Bennett. "I was brought up on this verandah and caged here for nine f..king days," he says. "They locked me in a wire cage during the day and at night they locked me in an old coal pit. It was total blackness in there. They threw me a blanket and a mat. Freezing cold. Goodnight. I was left like a trapped rat. How the f..k did they get away with it?" Tears fill his eyes; he tries to laugh them off.

"I've been in the worst prisons in Australia. Nothing was as bad as this place." He gazes at a bare paddock in front of the dorm. "I seen a kid, Joe Rowlands, running up and down in the hot sun behind a tractor down there. He was picking sticks up. Then I looked closer: He's f..kin' tied to the tractor. He collapsed. We carried him over to the water tank and poured water over his head for ten minutes. His jugular veins were popping out."

Swifte saw two options: be weak or be strong.

"I became a sadistic little bastard so I could survive against the older boys; the bigger boys. Bennett would bash me. He'd gut-kick me. I'll never forget this bloke sitting on me and he said, 'He's too tough for tears, Cap'. So Bennett bashed me senseless. And that's been me for the rest of my life, too tough for tears. Bottle it all up."

Inevitably, he was sent to Westbrook. "By the time I got out of Westbrook I was 16 and an angry young man," he says. "I came out and some junior says to me, 'I can get a job for you washing cars'. I said, 'How about I just rob banks, mate – f..k you'."

Years later, a Salvation Army officer visited Swifte inside Woodford men's prison. "Whatever happened to Vic Bennett?" Swifte asked.

"He died of a heart attack," the officer said.

"Where's he buried?" Swifte asked.

"Why do you ask?"

"Never mind," said Swifte. Pissing on graves, he figured, helps nobody. There were good people at Riverview – officers who carried out their work adhering to their pledge to God. One spoke to Qweekend under the strict condition that she remain anonymous. She worked at Riverview in the '60s when the home was run by Captain Reginald Cowling, the man McLeod says supervised the punishment parades.

The woman's late husband was a fellow Salvation Army officer and one of few men well-liked by the Riverview boys. "He was like a big brother," she said. "There was many a day he would come home crying because he was so concerned for the boys. When we were leaving some of the boys came to me and said, 'Who will we be able to talk to?' That's stayed with me for the rest of my life. They were good boys. They didn't deserve what was happening."

Shortly after leaving the home, she told a solicitor what she'd seen there. That solicitor wrote to the Salvation Army. Shortly after that, Cowling was posted to Rockhampton. McLeod says this single act was one of the life-changing moments of his youth, making his stay at Riverview that much more tolerable.

At the reunion, the men sit down to hear a speech from Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Cairns, the Salvation Army's Secretary of Personnel, based in Sydney. The farm is quiet but for a lone crow calling from the old manager's quarters.

"When I hear these things I just don't understand it," Cairns says. "It's against the very principles of everything the Salvation Army stands for. But these things happened. We want to say sorry to the people affected by this … If we in the Salvation Army can do anything to

support you, we want to do that and be part of your future in a much more positive way than some of you may have experienced in the past."

To the side of the gathering, Trevor Swifte lights a cigarette and stares at the dormitory verandah, lost in thought. "One final thing I'd say," says Lieutenant-Colonel Cairns, "is that I pray God's blessing is upon you."

20 minutes back towards Brisbane, 55-year-old criminologist Dr Merrelyn Bates opens a folder of faded papers concerning Riverview. Bates has devoted her adult life to child protection, social work and criminal justice. She sat on the Forde Foundation Board of Advice, and last year she met a group of Riverview boys at the farm.

Wally McLeod says meeting Bates did more for his healing than any meeting he's had with

a therapist, not just because she had a way of expressing in short, simple sentences the pain the boys were feeling, but simply because she took the turn off Ipswich Motorway and reached the end of Endeavour Street and passed through those farm gates. She was there, deeply troubled though she was about how the boys would greet the eldest child of Major Victor Bennett.

Bates remembers the teenage McLeod. She remembers all the boys. She nods her head at mention of the beatings some recall receiving from her father. She takes heart that time and truth haven't "blackened" the memory of her father quite like it has the officers guilty of sexual abuse. She accepts that some boys remember her father as a cruel man. And to them she offers insight.

"Towards the end at Riverview, my father was nothing but a grey, strained mess," she says. "The place nearly killed him. The pressure was incredible. The army didn't give him many officers. There was no support. The place was a dump; a hovel. He tried so hard to get the physical circumstances changed."

There are, indeed, articles in the Queensland Times and The Sunday Mail dating back to 1971reporting Bennett's bid to improve theinfrastructure at Riverview. He died of a heart attack in 1986. About that time Bates learned hehad suffered a heart attack while at Riverviewbut pressure – from the army, from the educationdepartment, from the boys – made him workthrough it. "When Dad was tired, his patiencewasn't as great," she says. "I would ask him,'Why do you do this? Look at you.' " She looksat her hands. "I know, and this is more from thepapers I've read, that the sodomy was happening,all of that. And I know my father was inconstant contact with the educationdepartment begging them to make changes."

No help came. Maybe God answered his prayers with the Brisbane flood of 1974. But the scales of the past can never be balanced – not for Victor Bennett, and not for the boys.

"I don't think money is going to make all that much difference," says Bates. "These kids' lives were compromised the day they walked into Riverview. Once a kid's life is compromised you can never fill that hole. These people are so stuck back there that they're looking for something magical that will change their lives. But there is no magic. Unfortunately, all they have is hard yards."

They walk a long road, the boys of the Riverview Training Farm. But there is a way, says Bates, to ease their journey. She closes the folder of files and smiles earnestly.

"By believing them," she says.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.