New Catholic Sex Abuse Findings:

Gay Priests Are Not the Problem

By David Gibson

Politics Daily

November 18, 2009

http://www.politicsdaily.com/2009/11/18/new-catholic-sex-abuse-findings-gay-priests-not-the-problem/

[See the Interim

Report, in the slide format presented to the USCCB.]

BALTIMORE — For much of the past decade it has been an article of

faith for many, bolstered by the testimony of thousands of victims, that

the Catholic priesthood is a haven for child molesters and that the Catholic

bishops have been particularly guilty of covering up for those abusers.

|

But preliminary results from a sweeping study of sexual abuse in the priesthood

show that the Catholic Church has been much like the rest of society in

terms of the incidence of abuse and the response by its institutional

leaders.

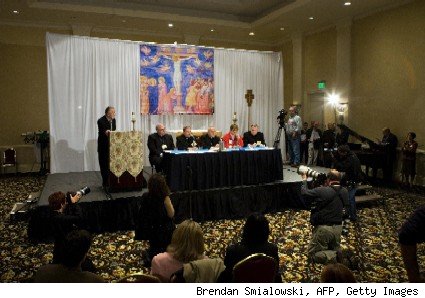

The data, which was presented to the U.S. hierarchy on the second day

of their annual meeting here, also appears to contradict the widely held

view that homosexuals in the priesthood were largely responsible for the

abuse.

"What we are suggesting is that the idea of sexual identity be separated

from the problem of sexual abuse," said Margaret Smith, a researcher

from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, which is conducting

an independent study of sexual abuse in the priesthood from 1950 up to

2002. "At this point, we do not find a connection between homosexual

identity and an increased likelihood of sexual abuse."

A second researcher, Karen Terry, also cautioned the bishops against making

a correlation between homosexuality in the priesthood and the high incidence

of abuse by priests against boys rather than girls — a ratio found

to be about 80-20.

"It's important to separate the sexual identity and the behavior,"

Terry said. "Someone can commit sexual acts that might be of a homosexual

nature but not have a homosexual identity." Terry said factors such

as greater access to boys is one reason for the skewed ratio. Smith also

raised the analogy of prison populations where homosexual behavior is

common even though the prisoners are not necessarily homosexuals, or cultures

where men are rigidly segregated from women until adulthood, and homosexual

activity is accepted and then ceases after marriage.

The sexual abuse scandal that erupted in January 2002 in Boston and spread

across the country led to what is considered the greatest crisis in the

history of American Catholicism, and the role of gay priests in the abuse

scandal has been a topic of heated debate inside and outside the church.

The belief that gay men were inordinately inclined to be abusers was one

reason the Vatican issued a controversial document in 2005 barring homosexuals

from the priesthood.

When asked by a bishop at Tuesday's meeting whether homosexuality should

be a factor in excluding men from the seminary, Smith responded, "If

that exclusion were based on the fact that that person would be more probable

than any other candidate to abuse, we do not find that at this time."

The John Jay study was commissioned by a blue-ribbon board of Catholic

lay people in November 2005 with the goal of exploring and explaining

exactly why the abuse occurred. An earlier study commissioned by the board,

with the cooperation of the bishops, found that more than 6,700 victims

were molested by nearly 4,400 priests over the five decades surveyed;

that represents about 4 percent of all the priests who served in the United

States over that time. The "causes and context" study, as it

is known, is scheduled to be completed by next fall.

The $1.8 million study is being underwritten largely by the bishops, who

have committed $1 million, and by donations from foundations and other

sources. The Department of Justice recently added $280,000 to the pot

in an indication of how unique and important this research can be. There

has been little solid research into the sexual abuse of children in part

because there have been so few available groups to study. The church's

extensive files on clergy personnel, revealed in lawsuits and news reports

or provided by dioceses, offered the necessary documentation, and is likely

to be of great interest to criminologists and to other institutions where

children interact with adults, from schools to community groups.

According to Terry and Smith, the Catholic experience — contrary

to popular belief — may be of wider relevance because it seems to

fall in line with what is known about abuse in society over that period.

"We have not found that the problem [the sexual abuse of minors]

is particular to the church," Smith told the bishops. "We have

found it to be similar to the problem in society."

"And in particular in other institutions," Terry added. "This

is something that is just starting to be researched right now by other

people within this field. They're looking at the whole mentoring relationship

. . . particularly adults and adolescents and the abuse that develops

in those relationships."

The research presented Tuesday by Terry and Smith certainly does not exonerate

the bishops, who were a chief target of criticism for doing little to

protect children from abusive priests over the years. That neglect continued

even after 1985, when the bishops first vowed to redress the abuses.

"The dioceses did respond to many cases of abuse," Terry said.

"However, their responses focused primarily on priests rather than

the victims. Their overwhelming focus was to find a resolution for the

priests. . . . While the diocesan leadership showed concern for the well-being

of the priest there was little evidence of concern for the well-being

of the victims."

By 1993, Terry said, "Policies that the leadership adopted were comprehensive,

though the implementation was limited in some dioceses."

Added Smith: "Maybe it's reasonable to say that in any institution

there is a period of time of development with new information and new

challenges, and there are policies articulated. However, to inhabit those

policies to the full sense of their ethical dimension takes time. And

that is what we see."

"This is not atypical. This is just the process of learning how to

respond to new challenges."

That is not to say that the bishops should not have done much more to

protect children, given their role as spiritual leaders and the message

that they preached. Similarly, church leaders say, they also expect more

of the priesthood than to be as liable to abuse as the rest of society.

While the study is still being completed, several contributing factors

to the rise in clergy abuse have emerged.

One is that the abuse resulted, in part, from a large influx of young

men into closed-off, old-fashioned seminaries during the 1940s and '50s,

a surge in vocations that was seen as a kind of "Golden Age"

in the priesthood, but one that was not accompanied by a corresponding

change in training to help weed out problematic personalities or to help

them mature into well-adjusted adults and priests.

The other major factor in the equation was the social upheaval of the

1960s and '70s, when the great majority of the abuse cases occurred. Sexual

abuse by priests closely corresponded to other social pathologies spiking

in America at the same time, such as drug use, criminality, and the breakdown

of the family. Men trained in closed seminary environments were not prepared

to deal with such turmoil, while men entering seminary in the 1960s and

'70s did so at a time of intense questioning and upheaval inside as well

as outside the church.

The John Jay researchers indicated that the clergy abusers tended to be

maladjusted men rather than the pathological abusers as they are often

portrayed. Indeed, less than one percent of the clergy abusers were true

pedophiles, that is, men who preyed on pre-pubescent children under 10.

Instead, they tended to have few victims and often committed a range of

other crimes or improper behaviors, which is similar to the profile of

abuse in the wider American society. "These are ordinary men,"

Smith said, echoing the verdict of a 1970 study of the psychological profile

of priests.

In her presentation, Terry said there were three popular misconceptions

relating to priests and abuse: One was that an increase in gay men entering

the seminaries in the 1970s led to more abuses; secondly, that abusers

were graduates of small, specialized seminaries; and third, that abusers

tended to be priests who entered what were called "minor seminaries,"

which began training seminarians as young as 13 years old. "We do

not have data to support any of these assertions," Terry said.

What is also clear from the research is that efforts to address abuse

by priests, starting in the mid-1980s, were effective — eventually.

Among those efforts were closer screening of seminarians and the addition

of so-called "human formation" programs to the seminary curriculum,

both of which were "critical" in reducing the incidence of abuse,

the researchers said. In addition, bishops, like the rest of American

society, became more aware of the terrible impact of sexual abuse on children.

Above all, the bishops came under increasing criticism over revelations

in the media that they had regularly protected abusers and shifted them

from parish to parish where they could abuse repeatedly. As a result,

after 1985 — the first wave of reforms instituted by the bishops

— it became 50 percent less likely that a clergy abuser would be

shifted to another parish and 50 percent more likely that he would be

placed on administrative leave.

Those anti-abuse policies were strengthened again in the 1990s following

further revelations, and the bishops finally adopted a zero tolerance,

one-strike policy for abusers in 2002 after the most recent and devastating

series of revelations of misdeeds by priests and bishops.

Critics point out that the bishops who covered up for abusers have not

faced any of the punishments that the priests suffered.

But the final version of the John Jay study is expected to include a detailed

treatment of why bishops did not act forcefully to stop the abuse of children

— the question for which everybody has their own answer, but without

much hard data to back them up.

For now, the bishops hope to hold out the American church as a model for

how to deal with abuse and ensure the safety of children.

"I think it's safe to say there is no safer place for children today

than in the Catholic Church," said Bishop Blase Cupich of South Dakota,

who presented the John Jay researchers to the other 230 bishops.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.