By John Nova Lomax

Houston Press

April 21, 2010

http://www.houstonpress.com/2010-04-22/news/the-man-who-sued-the-pope/

|

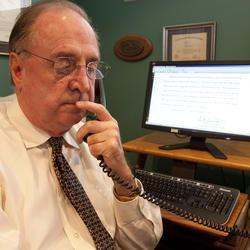

| The walls of Daniel Shea's River Oaks-area office are still adorned with his theological degrees from Belgium's ancient University of Louvain seminary, but Shea says the Roman Catholic Church he once solemnly vowed to serve no longer exists. Daniel Kramer |

Five years ago, Houston attorney/theologian Daniel Shea watched the results of the papal conclave at home. Intellectually, he knew what the dirty-gray smoke puffing out of the Sistine Chapel's chimney signaled: that Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger would soon be announced as the new Supreme Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church.

Now, as the white-haired Pope battles a seemingly endless series of priestly sex scandals, Shea says he is still trying to get his head around his belief that he and his co-counsel Tahira Khan Merritt set the coronation in motion when they filed a Houston-based sex abuse lawsuit against Ratzinger.

According to Shea, the cardinals elected Ratzinger Pope to give him the immunity that would enable him to avoid answering any questions concerning his knowledge about and handling of sex abuse cases in Houston's St. Francis De Sales church in the mid-1990s.

In fact, Shea believes that what he started with the lawsuit may eventually result in the destruction of the entire Roman Catholic Church.

Dan Shea, a former Catholic deacon, has come a long way from the seminary. Whether that's a long way up or a long way down depends on where today's Catholic Church stands in your eyes. In the last five years, Shea has cracked wise about the Pope being gay and a drag queen in front of the Italian Parliament. He got a bishop to declare in open court that it was the church's position that minor children were accomplices in their own molestation. He looked another bishop dead in the eye and told him to kiss his ass.

So it's safe to say, he evokes strong emotions while expressing his beliefs.

In Doe et al v. Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston-Houston et al, Shea and Khan Merritt allege that a letter then-Cardinal Ratzinger sent to every Catholic bishop on May 18, 2001, constituted an international conspiracy to obstruct justice. This official Vatican document Ratzinger penned in his role as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith dealt with official church procedure in dealing with clerical sex abuse cases.

Not only did this letter contain the cardinal's current thinking on the subject, it also cited in a footnote a top-secret 1962 Vatican document Shea would eventually flush out.

This 48-year-old document, informally known as Crimen Sollicitationis, considered a smoking gun in some quarters, contains written orders from the Vatican laying bare a system for protecting child molesters. To Shea, Crimen is more than a smoking gun, it is "a nuclear bomb."

Many churchmen disagree as to the true meaning of Crimen. Still, it's easy to interpret that, taken together, Crimen and Ratzinger's letter of May 18 make it plain that Ratzinger wanted these cases handled by the Vatican and only the Vatican. According to Ratzinger's letter, the roles "of judge, promoter of justice, notary and legal representative can validly be performed for these cases only by priests." Furthermore, the letter was co-signed by Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, who later went on the record as follows: "In my opinion, the demand that a bishop be obligated to contact the police in order to denounce a priest who has admitted the offense of pedophilia is unfounded."

The letter ordered everyone involved in these cases to keep the evidence confidential for ten years after the victims reached adulthood.

The entire proceedings were to be held under "pontifical secret," meaning those who broke the silence to outside authorities could be excommunicated.

"Every Cardinal in that conclave had been a recipient of the May 18 cover-up letter," Shea says. And because they were all recipients, he says, they were all complicit.

In response to Ratzinger's sending that letter, Shea and the Texas Secretary of State had already served his Vatican office with papers. The cardinal was scheduled to appear in federal Judge Lee Rosenthal's Houston courtroom.

What's more, the Pope would be giving his deposition to Shea, who is not just a tough plaintiff's lawyer, but also a former Catholic deacon with three postgraduate theological degrees one of them pontifical from the University of Louvain, one of the oldest Catholic universities in Europe.

"I don't think they were too pleased by that prospect," Shea says.

But now that he had been made Pope, it would be a cold day in hell before Joseph Ratzinger would darken the Rusk Street doorway of Rosenthal's court. As a newly minted head of state, Pope Benedict XVI was now diplomatically immune to American lawsuits.

Again, Shea believes that was the whole point behind Ratzinger's election.

____________________

Along with its Sharpstown surroundings, St. Francis De Sales was rapidly becoming Hispanicized in the 1990s. That was when Colombian native Juan Carlos Patino-Arango was brought in to minister to the growing Spanish-speaking portion of the flock, and he conducted most of the Spanish masses at the church. His accusers later swore that he was presented to them as a priest, not a mere seminarian.

According to court documents in Shea's lawsuit, Patino-Arango would offer to help counsel the boys about sex and masturbation topics some mothers don't want to broach with their sons. The suit alleges that these rectory "talks" escalated into Patino-Arango masturbating some of the boys and performing fellatio on one of them while masturbating himself. Some of the boys said he later threatened them after the fact by telling them that nobody would believe their stories over his, and also claimed that many of the other boys in the class had submitted to his "counseling," so they shouldn't feel too bad or abnormal.

After one of the boys reported the abuse to his parents, who in turn complained to the diocese, Patino-Arango was dismissed. Though the family of the first victim was told the seminarian had returned to Colombia, it was later alleged that he had instead been dispatched to Florida. (Eventually, Patino-Arango did return to Colombia on a flight paid for in large part by the diocese.) The suit alleges that at no time did the diocese or St. Francis publicly broach the topic of Patino-Arango's abrupt dismissal, nor did they reach out to any of the alleged victims.

The suit also contends that despite the claims to the contrary from the diocese, neither the Houston Police Department nor Child Protective Services were ever notified of Patino-Arango's alleged crimes.

CPS files are purged every three years, so that part of the diocese's claim could not be proven; HPD had no record of a report alleging abuse against Patino-Arango from 1995, though a warrant was issued years later, and he is currently a fugitive.

The suit went on to cite a 2004 research study conducted by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the behest of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. The study estimated that between 1960 and 2004, there had been 4,392 American pedophile priests with a total of 10,667 victims.

A report that accompanied the study stated that there had been a "significant surge" in abuse starting in the 1960s and continuing into the mid-1980s, the fallout of which was still then-continuing. "The bishops acknowledged that 'in the past secrecy has created an atmosphere that has inhibited the healing process and, in some cases, enabled sexually abusive behavior to be repeated.'" The report went on to say that "time and again church leaders failed to report incidents of possible criminal activity to the civil authorities."

It was and is Shea's belief that this secrecy was an official Vatican policy, and that Ratzinger's own writings as well as earlier official Vatican documents prove it. Specifically, in the latter category, there is Crimen.

Much but not all of Crimen deals specifically with how to proceed in cases in which a priest solicits sex while conducting the sacrament of confession. Which would seem to be enough luridness for any one document, but the last third of Crimen continues on to discuss something translatable from the Latin as "the worst crime": priestly sex with minors or "brute animals."

In those cases, the Vatican instructed that proceedings were to be conducted "in the most secretive way...restrained by a perpetual silence...and everyone [including the victim]...is to observe the strictest secret, which is commonly regarded as a secret of the Holy Office...under the penalty of excommunication." It also states that all investigations are to be conducted within the Church and that such jurisdiction ends ten years after the victim turns 18 years old.

Crimen did not mention anything about turning priests over to the law, nor did it mention any method of care for the victims of these cases.

Shea knew nothing of this document until 2001, when it was footnoted in Ratzinger's May 18 letter. "They put everything on the Web site in five languages, except this letter [of May 18] that was only in Latin," Shea says. "They think they are the only people who can still read Latin, but they forgot that there were people out there like me with pontifical degrees."

Not only does Shea, a former Roman Catholic deacon, have that degree, but he is also the kind of guy who assiduously reads and investigates footnotes. And appendices. He says the devil in Vatican documents is so often hidden in the footnotes and appendices. And it was in a footnote that he first saw mention of Crimen. He had an idea what would be in it from its title, but it would be two years before a full copy would be sent to him anonymously in the summer of 2003 in a plain brown envelope with no return address.

|

| In 1971, Shea looked forward to a lifetime of serving the Church as a deacon. Here he is still a seminarian and in Paris with a devout Catholic friend who insisted he wear a collar for their picture. Courtesy of Daniel Shea |

Tones of sickened wonder still creep into Shea's voice when he talks about Crimen. "There is literally a liturgical ceremony that a bishop uses to forgive a priest who has been indicted, and sends him on a pious pilgrimage," he says, lapsing into some of the language in the original document. "As long as the priest in his confession of guilt makes an acknowledgment that no one can be saved unless he believes what the Holy Roman Catholic Apostolic Church believes, teaches, professes and practices...So they use it to promulgate that bullshit idea that there's no salvation outside the Roman Catholic Church. So as long as the priest is willing to do that, he gets a get-out-of-jail-free card."

To Shea, it gives the lie to the notion that the waves upon waves of cover-ups have been the work of a few bad apples. On the contrary, he says, Crimen proves that the rot came from inside the apple tree. The scandal was no longer an indictment of a seemingly endless procession of grievously flawed men, but of an organization that was involved in an international conspiracy to obstruct justice.

Shea stands by that assessment today, and as you might expect, several plaintiff's attorneys agree with him. One such is Khan Merritt. "Crimen shows that [the "cover-up"] has been going on a long time, that there's a pattern and that the church has a procedure in place," she says.

Boston's Carmen Durso wrote a letter to U.S. Attorney Michael J. Sullivan claiming that Crimen "may provide the link in the thinking of all of those who hid the truth for so many years. The constant admonitions that information regarding accusations against priests are to be deemed 'a secret of the Holy Office' may explain, but most certainly do not justify, their actions."

The faithful saw it differently. A Canadian oblate Father Francis Morrisey of Saint Paul University in Ottawa told the National Catholic Reporter in 2003 that there was nothing in it that prevented a crime against a minor being reported to the police. "Of course, a bishop couldn't use this document to cover up denunciation of an act of sexual abuse," Morrisey said. "The document simply wasn't made for that purpose."

The Reverend Ladislas Orsy S.J., a professor of canon law at Georgetown, had what some would term a typically nuanced, Jesuitical spin on the document. "This document reflects a mentality and a policy. I do not think [Crimen] initiated it."

You would expect the faithful to spin the document one way and plaintiff's attorneys another. One of the closest approximations to an honest broker in the Crimen affair has been Father Thomas Doyle, a dissident priest, canon lawyer and dogged pursuer of pedophiles in the church. Doyle, who has been an expert witness for dozens of victims, was something of a voice crying in the wilderness on the subject long before the scandal broke. He has since often stated what he thinks the Church should do now: Defrock the priests, turn them over to the cops and stop trying to sweep the scandals under the rug.

Doyle's interpretation of Crimen has been maddeningly inconsistent. In 2006, he was featured in a BBC documentary that is still online and uncorrected saying that Crimen was "an explicit written policy to cover up cases of child sexual abuse by the clergy [and] to punish those who would call attention to these crimes by the churchmen." He also said that Crimen was "clear written evidence of the fact that all they are concerned about is containing and controlling the problem."

In March of this year, he published a paper that seemed to indicate that he had changed his mind. "[Crimen] and its predecessor from 1922 are not proof of an explicit world-wide conspiracy to cover up clergy sex crimes," he wrote. "It seems more accurate to assess both statements as indications of an official policy of secrecy rather than a conspiracy of cover-up."

"An official policy of secrecy, once you're keeping secret a criminal act, is called obstruction of justice," Shea retorts. "Tom doesn't understand that. He is not a civil lawyer. He only understands the common term 'cover-up.' Legally, it is known as obstruction of justice.'"

Doyle imputes some of this policy of secrecy to more or less noble motives, such as the protection of the sacrament of confession and the prevention of false accusations, but also grants that much of the desire for secrecy came from a desire to avoid scandal and damage to the reputation of the clergy. Crimen "did not create the obsession with secrecy," he writes, but is a result of a centuries-old policy of silence.

Doesn't matter, says Shea. It's still obstruction of justice. He even says an FBI agent agreed with him seven years ago.

Shea recalls mailing an agent who now works for another agency and did not want to be identified Crimen and other documents. At first, the agent told him that his case might not fly, as John Ashcroft's Talibanesque Justice Department was not all that interested in pursuing cases against religious organizations.

Nevertheless, Shea says the agent called him back the next day and left him a message saying that after reviewing the documents, she believed they constituted "nothing less than an international conspiracy to obstruct justice." The agent told him she was "gonna run it up the flagpole."

Shea says he called the agent back the very next day, only to find that she had been transferred. "They yanked that flagpole right out from under her," Shea says. (For her part, the agent says that her transfer had nothing to do with Shea, and that she doesn't recall if she told him he had a conspiracy on his hands.)

All this is important because of what happens when you let these people off the hook, Shea says. Take Patino-Arango, for example...Let's just say that were it not for the fact that Colombia has no extradition treaty with the United States, perhaps he might not be so bold as to have a Facebook page under his own name. But since the United States does not, he does. And very many of the thirtysomething's latest new Facebook friends look to be about the same age as the three John Does in the lawsuit.

Ask Dan Shea to answer a simple direct question and prepare to end up getting a discourse on everything from, just for example, Pope Leo XIII, the French Revolution and the Council of Trent. (A gifted mimic, Shea delivers these screeds in accents ranging from Polish to French to Italian wiseguy to exaggerations of his own fading Family Guy-like Rhode Island bray.)

And save for the mimicry, when he takes up a sex abuse case, he marshals all that intellectual weight in order to put the entire last 1,700 years of Catholic tradition on trial. In a suit active in Corpus Christi right now, he does that pretty much explicitly, with pleadings harking back to the Emperor Constantine in 313 AD. There's a method to it: He believes it's necessary to show that the church's ancient traditional culture has bred an ongoing criminal conspiracy to obstruct justice.

Not that his knowledge of church workings is confined to ancient history. "Dan's a smart and relentless advocate for the victims he represents," says David Clohessy, the national director of the Survivors' Network of those Abused by Priests. "He's got an advantage over many attorneys because he clearly understands the arcane workings and obscure lingo of the church hierarchy. He isn't ever intimidated by all the legal maneuvers that Catholic defense lawyers exploit to try and keep bishops out of the witness box."

Tahira Khan Merritt, the Dallas lawyer with whom Shea had served as co-counsel on the Houston case, says that she appreciates both his knowledge of the workings of the Vatican and his historical perspective.

In a sworn affidavit in another of Shea's famous cases when he helped sue Harris County District Judge John Devine in order to get Devine to take down the Ten Commandments he had hanging on his court's walls former South Texas College of Law president and dean William Wilks said that Shea was "among the first rank of lawyers with interdisciplinary competence in the field of church-state relations."

It's an old obsession of Shea's, one he picked up from his father back in Providence. Shea says that in the south Providence, Rhode Island of his Irish Catholic youth, he wouldn't have known a Protestant or a Republican if he fell over one. His dad was a no-bullshit quality control engineer, and nothing irked him more than politicians who advertised their faith. (Shea says that seeing the Ten Commandments on the walls of Judge Devine's courtroom made him feel like his father's son for the very first time.)

Not that his father was antichurch. Shea was an altar boy at St. Michael's and the lead singer in the children's choir. At 17, he was at loggerheads with his dad "Like most Irish families, by the time I was a teenager, he wanted to kill me and I wanted to kill him" so he ran away to the Navy, where he drew submarine duty. He quickly became one of the youngest nuclear-reactor operators in the Navy, and now says that sub duty was the formative experience of his life.

Pictures of two submarines are hung proudly on the walls of his River Oaks-area office. "You can't engage in self-deception in a submarine," he said. "You can't look at a meter and tell yourself, 'This isn't happening.' It's about facts. You've gotta say, 'This is what's happening, I have to go do this now!'"

That training has guided him ever since, he says. Along with his hardwiring from his dad in the Devine case, it guided him then. And it was there when he ended his formal involvement with the Catholic Church in the mid-'70s.

After mustering out of the Navy in the early '60s, Shea was at something of a loose end. He says that the Catholic Church was an exciting institution in those days, full of intellectual ferment in the run-up to Vatican II. Two bishops of his acquaintance told him that the church needed men of his brainpower and drive to help guide the church into its new frontier, so off he went to seminary in Louvain. Not long after his studies were completed, he says, the conservatives in the Vatican had undone much of what Vatican II had set in motion. A priest told him flat-out that the church needed "parish priests, not smart guys" like Shea, who served as a deacon for about a year before quitting.

"The church I was trained to work in no longer existed," he says.

Nevertheless, he still regularly attended Mass, but fell back on his Navy nuclear training to find work. For much of the '70s, he had very good jobs working for companies that built nuclear plants, but that industry started to die with Three Mile Island and then croaked completely after Chernobyl, but not before the East Coast company Shea was working for was bought by Brown & Root, who transferred Shea to Texas. In Houston, he was the organist at Midtown's Holy Rosary Church for many years.

In 1990, Shea got his law degree. Roughly ten years later he won a big case. He bought a yacht, decorated its prow with a shamrock and named it Seriatim, but he also wanted to give back to his faith.

St. Michael's, his old parish church back in Providence, had fallen on hard times. The Irish had moved out, their place taken by waves of impoverished immigrants from Latin America and Africa, and Shea responded to a plea to restore the church's organ. He donated $125,000, and Daniel Reilly, a former St. Michael's parishioner who had gone on to become the Bishop of Worcester, Massachusetts, came to the dedication along with the bishop of Providence. "We got a private concert," Shea remembers. "It was just beautiful."

Less than a year later, Reilly would be calling Shea a traitor, and Shea would be suing Reilly on behalf of several victims of a particularly nasty case of priestly abuse, in which the priest in question was allegedly anally raping altar boys on the altar.

"They made the mistake of leaving me alone with him in the conference room, and I looked at him and said, 'Dan Reilly, what the fuck have you been doing?" Shea remembers. "You ought to be ashamed of yourself. If Henry Shelley" a much-beloved long-dead priest and coach at St. Michael's "were in this room today, he would kick your ass.'"

Shea says that Reilly looked at him as if nobody had ever spoken to him a bishop! like that before. Shea didn't care, and pressed on: 'Well, kiss my royal Irish ass, Dan Reilly, because you're a piece of shit.'"

____________________

That wicked irreverence has come more to the fore as his traditional faith has lapsed. A few years ago, an Italian political party asked him to address that country's parliament in Rome. His topic was the separation of church and state, but he soon moved on to other, lighter fare. "After my formal presentation, I started talking about Ratzinger and I said, 'Who the hell is he trying to kid? This guy wears enough gold lame in all of his vestments to suit up three New York drag queens. And furthermore, he's given drag queens a bad name. I mean, look at his Palm Sunday vestments. They're supposed to be red, but his are so gold-encrusted you can barely see the red. He's got Gucci shoes and Prada glasses, and have you seen the boyfriend? He's a hunk a German tennis player and a jet fighter pilot, Gorgeous Georg. I've never seen a bishop who didn't have an extraordinarily handsome private secretary."

|

| Shea, seen here in civilian clothes with his crewmates from the USS Cavalla in 1961, says that his time aboard submarines formed his personality. "You can't engage in self-deception in a submarine," he says. "You can't look at a meter and tell yourself, 'This isn't happening.'" (And yes, Shea served aboard the same sub that is now anchored in Galveston's Seawolf Park.) Courtesy of Daniel Shea |

Today, he says he won't set foot in a Catholic church and has left instructions that no priest is to get anywhere near his body after his death. "You have to go that far. You have to get so angry...I had to get so goddamn angry...Really, it's only been in the last year that I have come to peace with the fact that I am never gonna darken the doorstep of another Catholic church again," he says. Churchgoing Catholics are part of the problem, he says. "They're shelling out the money, going, 'Oh fa-ther, fa-ther.'"

Meanwhile, he is one of those rare people whose life is their work. Several of his obsessions the conservative counterrevolution in the post-Vatican II Catholic Church and the separation of church and state are bound up in the Catholic Church's sex scandals, and as an attorney, he has the power to fight to effect change. (As an out and proud gay man, he also has issues with some of the church's teachings on homosexuality.)

And perhaps his fondest wish is to see the current Pope put on a witness stand or even arrested. It saddens him that this country the proud home of the First Amendment probably won't be the one to do it, nor will he be the lawyer to grill the man he loves to call plain old Joseph Ratzinger.

Shea says one of the first questions he wanted to ask Ratzinger was if he would be willing to clarify the words of one of his underlings, auxiliary Bishop George Rueger, with whom Shea once had the following courtroom exchange:

Daniel Shea: I'm trying to get a sense of this idea that if a cleric becomes involved in sexual conduct with a minor, that somehow this is a sin committed obviously by the cleric, but with the minor, that the minor is sinning along with the priest. I think you've indicated that frankly you believe that that may or may not be true, but it's possible that that could be correct; is that right?

Rueger: "He is sinning with a minor, the minor is his accomplice. What the gravity of the minor's culpability is is hard to say."

"They truly believe these children are accomplices," Shea says in wonder. "That's the sworn testimony of a bishop, and he says it without hesitation."

And he came so close...Even after Ratzinger became Benedict XVI, Shea's case was still grinding along in Judge Lee Rosenthal's federal courtroom on Rusk Street. After his election, Shea and co-counsel Khan Merritt knew that the jig was up, and not long after the conclave, a Vatican diplomat sent word to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice asking her to invoke Ratzinger's immunity.

Rosenthal was evidently unimpressed by the stature of the man in her case. In a remarkable order of hers signed on June 23 (more than ten weeks after he became Pope Benedict XVI), Rosenthal referred to Ratzinger by the name his mother gave him and told his Holiness in no uncertain terms exactly what she expected of him.

"Defendant Joseph Ratzinger must file a memorandum in support of his motion seeking dismissal based on head-of-state immunity no later than 30 days after the United States Department of State's suggestion of immunity is submitted to the court," the order read in part. Later, Rosenthal went on to decree that "Defendant Joseph Ratzinger" was to "file a report by July 29, 2005 and every 30 days thereafter informing the court of the status" of his request for immunity.

"For the first time in Western history, you've got a Pope who's been under the jurisdiction of the United States, and a female Jewish federal judge telling Joseph Ratzinger, who also happens to be Pope, that he's gotta do this and that before he's let out of her lawsuit," marvels Shea. "That's a watermark in United States history and in the history of the United States Constitution." (Rosenthal's court did not return a phone call from the Houston Press asking her to clarify her thought processes in its crafting.)

|

| Papal secretary Georg "Gorgeous Georg" Gaenswein slaps skin with Pope Benedict XVI last year. "I've never seen a bishop who didn't have an extraordinarily handsome private secretary," Shea laughs. |

In August of 2005, Rice's office sent a letter to Assistant Attorney General Peter Keisler informing Keisler that the Department of State recognized and allowed Benedict's immunity. The letter went on to stress the "particular importance attached by the United States to obtaining the prompt dismissal of the present proceedings...in view of the significant foreign policy implications of such an action against the Head of a foreign state."

And that was that.

Until very recently, when the sex scandals in Germany, Wisconsin and California flared anew. While Shea's case isn't being reopened, there are others in places like Germany. He thinks that the Germans might just have the nerve American officials lack. "They are more secular and less tolerant of this bullshit," he says. "I have forwarded the German Justice minister my documents, and the feedback I've been getting makes me believe that they see them the way that [FBI agent] did."

He rails against the Vatican's diplomatic immunity. Why stop with the Vatican, he wonders. "If you recognize the papacy, why not go out to Salt Lake City and draw a map around the Mormon temple square, and we'll call it Temple City, and we'll make the Head Brouhaha of the Mormon Church a head of state, and the same thing with the Southern Baptists. Maybe we could draw a circle around Baylor University.

"It's patently contrary to the spirit of the Constitution."

He still believes that his old lawsuit could bring down the Pope by other means. He is still hoping that someone will come along and find that the conclave was tainted. He wishes that the Vatican would operate with some semblance of what he would call justice.

"There's a difference between what we would call actual impropriety and the appearance of impropriety," he says. "In a case involving judges, should anything appear that causes the appearance of impropriety, a judge is supposed to recuse himself. And that recusal is not seen as an admission of any actual impropriety."

Shea believes that Ratzinger's invocation of Crimen and authorship of the May 18, 2001, letter constitutes more than enough evidence for the man in the street to wonder if maybe there was some chance of impropriety in the papal conclave. "The appearance of a tainted conclave is there," Shea says. "That's why the person who is the product of a tainted conclave could well decide to resign the papacy and say with a straight face, 'There was no impropriety. There exists an appearance of impropriety, and out of my concern for the integrity of the papacy and the integrity of the College of Cardinals, I feel it appropriate to step aside.'"

The Church requires the confidence of its faithful in its institutions, he says, and adds that both the integrity of the papacy and the moral integrity of the Church have been shattered. Nevertheless, he thinks that the Pope will keep digging in. Recent events the Pope's personal preacher comparing the plight of today's church to that of Jews in the Holocaust, the reference to sex abuse scandals as "petty gossip" seem to bear him out.

What's more, he believes they are still hiding the devil in the details. He believes that the so-called Essential Norms document of 2002, which the Vatican has touted as a watershed in its dealing with sex abuse i.e., priests will be handed over to the police and not transferred any longer is made voidable by the last few clauses in the last sentence of the seventh and last footnote, which read "the Church reaffirms her right to enact legislation binding on all her members concerning the ecclesiastical dimensions of the delict [sin] of sexual abuse of minors."

"It's always in the footnotes," he says. "The devil is always in the small print."

Contact: john.lomax@houstonpress.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.