By Bill McGarvey

Busted Halo

May 12, 2010

http://www.bustedhalo.com/features/one-parents-demand-for-justice/

When I met David Spotanski at a conference on leadership in the Catholic Church in 2007, my first impression of the Belleville, Ill., native was that he was like so many of the Midwesterners whom I've known and worked with over the years: friendly, approachable, and not in the habit of taking himself too seriously. The fact that, as a layman, Spotanski also happened to be the chancellor for the Belleville diocese just outside of St. Louis for all matters except canonical issues requiring a priest seemed a little unusual. But after a number of conversations over the course of the gathering it became clear to me that if this married father of three was indicative of the sort of leadership in the Catholic Church's future, the Church was in very capable hands.

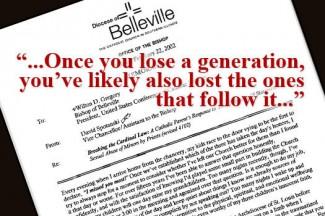

I wasn't prepared, however, for the information Spotanski decided to share with me at the end of our meeting. Before returning home, he left me with a 10-page photocopied document that contained what was easily the most personal, honest and moving commentary I had yet to read on the sex abuse scandal. It was blunt, unsparing and deeply challenging language from someone who worked for the Church, clearly loved his Catholic faith and was deeply concerned that the Church's leadership wasn't able to comprehend how badly its credibility had been damaged.

But what made his letter so unique was that he had hand delivered and read it aloud privately to his boss, Bishop Wilton Gregory. At the time, Gregory was not only the bishop of Belleville but also had just taken over as the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, in which he was forced to deal with the horrible scandal that had begun erupting across the country.

A Father's Perspective

In the letter, Spotanski 39 at the time he wrote it spoke movingly as a husband and father. "I may work in your chancery," he told his bishop/boss "but I am, above all else, Sharon's husband and Erin, Jonathan and James' dad." He continued, "The truth is our bishops are not doing all they can to stop the sexual abuse of minors by their brother priests; they're each doing all they care to . For a Church that can be so outspoken and uncompromising about the splinters in the eyes of our culture, She has apparently for decades concealed a plank in Her own eye from which one could hew an ark." As if his words weren't sufficient, Spotanski also attached a recent photo of his three young children to his letter.

|

In addition to such pointed and impassioned criticism, Spotanski's memo to the USCCB president also included constructive ideas for how the bishops could substantively change policy about the protection of minors in the future. Spotanski's suggestions included the need to craft a national policy on sex abuse that needed to be enforced by an independent body and led by a parent who'd be the church version of a "director of homeland security." The debate and voting on any policy changes needed to be in full view of the press and televised, he said, and Bishops found to have violated the trust that is placed in them as shepherds of their flocks by leaving criminal abusers in ministry must be reviewed for fitness as leaders.

Taken to Heart

To Bishop Gregory's credit, he clearly took Spotanski's message to heart. Many of the policy changes enacted by the USCCB that year reflected the ideas laid out in that memo. In the days and years that followed, Spotanski shared the document with those he came in contact with in both church and media circles and it quietly fell into the hands of many of the people charged with enacting change.

Despite numerous requests to publish it (from me at Busted Halo as well as a number of major metropolitan daily papers) Spotanski opted not to. But with the recent revelations of abuse across Europe and the defensive responses from certain quarters he felt that it was time to speak out.

In an article in The St. Louis Beacon he revealed the contents of his candid letter to Bishop Gregory. Gregory, now the archbishop of Atlanta, corroborated Spotanski's account in an interview for the article with St. Louis-based religion reporter Patricia Rice, commenting, "I learned from David I think he is a great man with a great heart. He spoke to me on two different levels: as someone on my staff that I depended on but also as a father." The piece's author also went on record for the first time regarding an encounter with Bishop Gregory from April 2002. After the summit in Rome in which Bishop Gregory and all the American cardinals met with Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI) to discuss the scandal, Gregory referring to Spotanski's memo commented "I've listened to Dave."

|

| Archbishop Wilton Gregory |

Spotanski's real reason for releasing the letter is his concern for the future of the church. The fact that Busted Halo speaks to a younger audience that he hopes might take part in that future is why he approached us to publish his 2002 letter as well. We urge you not only to read the original text of his moving correspondence with Archbishop Gregory (attached here as a PDF) but also to read our exclusive interview with Spotanski below in which he discusses his current thoughts on the seemingly never-ending story of sex abuse in the Church.

BH: What do you hope can come from revealing this now?

DS: I recently read an article written by a bishop for whom I have a world of respect. The gist of the column was that all the way back to the time of the disciples, except for Jesus Himself the leaders of the Church have been deeply, miserably flawed individuals who, by the sheer imperfect nature of their humanity, have repeatedly done harm to the Church. The very valid point this bishop was trying to make was that it's not the hierarchy's Church, it's Christ's, and it's Christ in Whom we place our faith.

When I read the article, though, I worried that some people would interpret it as though he was saying, "Look, we've been upfront with you for centuries. We've told you all that since the Church began the leadership has been 'sinful,' 'stupid,' 'stubborn,' 'hardheaded,' and 'ignorant,' all the way back to Judas turning Jesus over, Peter denying Him three times, and the others abandoning Him. Yet somehow you all never made the connection, and now you're telling us you're somehow surprised and upset that we bishops were a little negligent and some of you got abused? Well, that's not our fault."

Of course, that's not what he meant, although if you read his article with a certain preconceived mindset, you could make that case. When the story was written about my involvement in 2002, most accepted it for what it was a demonstration of how Church can and must work if we're to get past this, about how a bishop and his advisors worked together to craft a sensitive response to an scandal of epic proportion. Some, though, chose to read the story as "it took a layman to get through to them," which was neither the intent nor the truth. I'm grateful for this opportunity to clarify that.

I also think it's important on occasion to remind ourselves that the only affiliation that's required to speak up in this Church is baptism. From that moment forward we are full-fledged members with a God-given right and a God-driven obligation to help fix what's wrong in our Church and in the world.

It's unsettling to consider that no American under the age of 25 remembers an untainted Catholic Church. It's naïve of us to think that won't make our young people assess their lifelong commitment to Catholicism over another faith or none at all a thousand times more closely than people my age and older did. Instead of walking away, though, I hope they're energized to work for the changes necessary to make this an institution in which they will be proud to raise their young families. It will ultimately fall to the people in their twenties and thirties now to decide if we've done enough, and if we've done it in time. I don't want to stand before God someday knowing there was something more I should have said or done.

BH: Why did you wait eight years to release this letter?

DS: It was less a matter of releasing it than of publicly acknowledging it on my own terms. Early on I gave copies to a few people friends, family, colleagues in my own diocese and others, and even members of the USCCB staff and the National Review Board some for feedback, others because I sensed they shared my passion for fixing this once and for all. If it resonated with them, they would often pass it on to others, including in some cases members of the media who would then contact me and ask if they could write about both the text and the remarkable bishop who encouraged that kind of candor. Because the document was so profoundly personal and involved my young children, I'd always ask them not to. To their credit, every single reporter honored that request. There just never seemed to be a reason to put it out there that didn't seem self-serving. I certainly never imagined it would still be relevant eight years after the fact, or that the arc of events and errors in Europe today would so closely mirror those of the Church in the United States in 2002.

Not long after the most recent international revelations began, interest from the media picked up, particularly as they tried to localize a story taking place an ocean away. If there's any lesson we in the Church should have learned by now, but still seem to struggle with, it's that disclosure is always better than discovery.

BH: What inspired you to write it in the first place?

DS: The same sense of stunned disbelief that overcame every Catholic parent when the sheer magnitude of these revelations was becoming clear. During a conversation in early 2002 with a number of guys I play ball with, we realized that nearly every one of us had some indirect personal connection to clerical abuse of minors. One had been married by a priest who was later removed from ministry; another had young relatives who had been abused by a cleric. I'd personally lived in two parishes from which the associate pastors were eventually removed. As parents, Catholic or not, that was a really sobering realization. I still recall how I wished then-Bishop Gregory had been there that night to hear that conversation. Since he wasn't, I thought I owed it to him, my wife, my kids and my teammates to try to articulate one dad's perspective.

Ultimately, as it says in the text, I knew a day would come when I would need to be able to look each of my children in the eye and assure them I spoke up on their behalf. Even more than that, I wanted this tragedy to be ancient history by the time my kids had kids of their own. It looks now like that probably won't happen.

BH: How was it received at the time?

DS: I've been blessed to work for a number of bishops who hired me to tell them what I thought, and then actually expected me to do that. Over the years I've seen lots of very articulate and outspoken people become almost woefully deferential in the company of bishops and priests, even when their hearts were breaking. That's a cultural dynamic that doesn't serve us well and, I've learned, is often just as frustrating for both parties.

I first handed the text to Bishop Gregory to read at his residence, but then I took it back and read the whole thing aloud to him so he'd receive it not as a memorandum from a member of his staff, but as an honest plea from a Catholic dad who couldn't settle on an emotion confusion, rage, disgust, disappointment, and maybe even a sense of relief that this was out in the open and would have to be addressed before any more kids could get hurt. The language was harsh and direct because I felt then as I do now that the moment for polite discourse had passed. It was deliberately not political or ideological because the scourge of priests abusing children is not political or ideological. There is no right and left in this; there's only right and wrong.

That afternoon I put a vacation photo of my kids, taken the previous summer, squarely in the middle of his desk, where it remained. I printed twenty more copies and stuck them in his meeting packets, speech texts, on the podium anywhere I felt it might help to remind him of what was at stake while he attended the upcoming conference of Bishops in Dallas.

I think he heard what I'd written as it was intended, as both an indictment and a genuine offer to help. I'd also like to think similar conversations were going on in every chancery in the country.

BH: Do you think it made any difference at all in the church's policy on the scandal?

DS: Only in that it was generally consistent with the proposals set forth by just about every bishop willing to engage in gut-wrenchingly honest dialogue with their own staffs and advisors. My first piece of advice to my own bishop was, if this is the only place you hear any of these suggestions you would do well to summarily disregard them. If, however, you hear these or similar proposals across the board, you and your brother bishops need to get to work.

Of course, Bishop Gregory did hear similar calls from his diocesan pastoral council, his staff at the USCCB and the diocese, and just about every bishop, priest, deacon and lay person he encountered over the next several months. Though some were slower than others to accept what was being alleged, by late spring of 2002 I would say that anger and a sense of betrayal among Catholic parents was nearly universal sometimes temporarily smothered by guilt over being so angry at their Church, but still universal.

To be honest, though, it saddens me to admit that a closer look at the specific proposals I made in 2002 reveals that they mostly have not been implemented, at least not as conceived. In fact, rereading the document for the first time in a while recently made me wonder what if anything I'd be able to delete if I were writing it today.

For example, every diocese is supposed to have a review board whose job it is to recommend fitness for ministry of priests accused of sexual misconduct with minors, regardless of how long ago the abuse is alleged to have happened. There's no canonical precedent for it and it was understandably unsettling to our priests, but it was widely regarded as a necessary step to broaden professional involvement in assessing the validity of a particular allegation. When I proposed a national review board, it was intended to take the notion of a diocesan review board one step further: a group of professionals of complementary disciplines who would assess the facts documentation, depositions and actions regarding a particular bishop's response to allegations involving his priests and then determine his fitness for continued episcopal ministry. They would then make a recommendation to the Holy Father, as a diocesan review board does to the local bishop, based on whether they believed the man was, say, "acting on the best advice of his experts at the time," or merely avoiding his fundamental responsibility to protect the people of God in his pastoral care. Again, there's no canonical precedent, but, I reasoned, leadership should always be prepared to model to a higher degree any standard to which they hold their subordinates. Besides, for many of us, that was the more egregious scandal.

By the time the actual National Review Board was formed, of course, it didn't look anything like that. What was created is invaluable, but it aligns with what I proposed in name only, which of course was the prerogative of the designers. Now that resignations of bishops are being accepted more frequently as an apparent result of their mishandling of misconduct allegations, it would seem sensible to try to determine some objective criteria and a process to slow down the dominoes.

Also in 2002, I proposed that those dioceses overseen by bishops who refuse to participate in the new reporting procedures should be investigated to ensure they're in full compliance with what became the charter and the norms. As we know, that hasn't happened either, and we owe a debt of gratitude to those bishops who have flaunted their deliberate lack of participation. Wearing the public revelation of their resistance like a badge of honor, they have demonstrated unequivocally that, institutionally anyway, individual bishops are still permitted to do as much or as little as they choose to protect our children.

BH: What should the Church be doing now?

DS: Society has come a long way in its understanding of child sexual abuse and those who commit it in the last several years, but we've had a lot of time to get this right. I think nearly every bishop is committed to doing things absolutely in the best interest of their faith community at this point, and obviously anyone named to the episcopacy in the past eight years deserves to start with a clean slate. Those bishops who still haven't got it right and those who allow them to remain in ministry need to understand how their respective arrogance and indifference are compromising our ability to put this behind us for good.

I was asked recently what advice I'd give the bishops today, and these three things came to mind immediately:

We have to stop making rules without consequences.

We have to stop patting ourselves on the back for quickly enacting policies our people reasonably presumed had been in place for 2,000 years.

We have to stop comparing our crisis-driven responses to those of secular institutions for which we were all taught the Church would be our secure, God-given sanctuary when those worldly institutions inevitably failed us.

I would add to that a renewed sense of urgency. I closed my 2002 memorandum this way: "More than anything else, Christ's Church should be about preserving and promoting innocence, not accelerating its ruin. Pardon the platitude, but it's time we stopped protecting our past and did something to fortify our future." We don't have the luxury of "thinking in centuries" any longer, and we're running out of second chances.

BH: You did this for your kids. What are your hopes for them in terms of the Church?

DS: A couple of weeks ago I was at a meeting out in my diocese and, as it regularly does again these days, this topic came up. Really good people were asking really hard questions about the most recent news and I flashed back to almost identical discussions in 2002, except that instead of being one of the youngest people in the room I was now a contemporary of most of the participants. It startled me that there was no one in the room filling the demographic I left behind when I moved kicking and screaming into "45-54."

But then I experienced one of the most inspiring moments since this all started. A very young priest of our diocese, ordained in the years since Boston and the charter, started speaking about the scandal, the sin, the wounds and the whole crisis in a way that betrayed a depth of pastoral understanding that left even cynical me speechless. He was articulate. He was precise. He didn't bob and weave or try to avoid or dismiss. He didn't blame this scandal on the left, or the right, or the media. He listened carefully, he responded pastorally. He wasn't embarrassed and he didn't hold back. He didn't pepper us with paper-thin talking points about how statistically we're less likely to be abused by a priest than a scoutmaster. Or how we've developed the best prevention programs on the planet you know, now that we've had to. He comforted and assured those present that if we let Him work through us, God would make all things new. I was profoundly proud of him and I was genuinely hopeful for us.

Somewhere on the drive home that evening it hit me that I may have just had my first glimpse of a healthier, holier, humbler Catholic Church that may still be a ways off, but is coming the Catholic Church my grandparents, parents, and I thought we'd belonged to all along. The Catholic Church we owe our kids.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.