Orange Coast

August 27 2010

http://www.orangecoastmagazine.com/article2.aspx?id=24210

|

Sunday Mass is under way at St. Angela Merici Catholic Church in Brea. It’s barely 10 a.m. and the temperature already is in the mid-80s, but inside the sanctuary the air remains cool as the priest preaches to the faithful that God is always present.

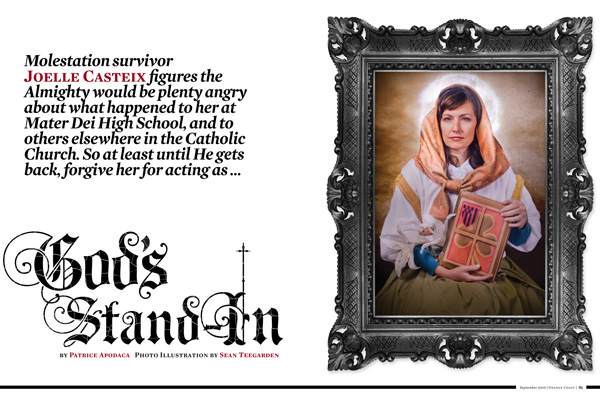

Outside on the hot pavement, Joelle Casteix waits. As Mass concludes and the church empties, Casteix quietly approaches departing worshippers and hands them fliers accusing Diocese of Orange Bishop Tod D. Brown of shielding clerics accused of sexual misconduct and failing to warn parishioners of alleged molesters in their midst. “Please HELP US Keep Kids Safe and Protect Victims,” the fliers exhort.

Most of the churchgoers accept the handout silently and move on. Some deposit the fliers in a nearby trash can. A few ask questions and offer support. One woman repeatedly tells Casteix, “I don’t think you’re supposed to be here.” The woman goes back inside, then moments later a church representative emerges. His tone is polite but firm as he cautions Casteix to stay off church property, and it’s tough to miss that he outweighs her by about 100 pounds. She takes a step back, checks to see that her feet are planted on the public sidewalk, and murmurs, “They always send the biggest guys out to deal with me.”

In her denim capris, sensible sandals, and baseball cap, Casteix hardly looks threatening. She is a molestation survivor whose goal-nothing less than the eradication of child sexual abuse-might seem like a quixotic quest, admirable in its intent, but foolishly idealistic. She easily could be dismissed as misguided or eccentric, a grown-up Holden Caulfield who fantasizes about saving children from falling off a cliff. Days like this can make her vision of protecting children seem all the more improbable.

But Casteix is undaunted, likening herself not to a fictional would-be hero, but to something more practical: a termite that eventually can conquer a forest, with the help of other termites. "My goals are transparency, accountability, and justice," she says. "You have those, we'll get kids to a port, we'll get criminals behind bars, and we'll be safe."

The Newport Beach activist, who turns 40 in October, is a former writer and public relations professional who received $1.6 million in 2005 as part of the $100 million settlement of a civil case against the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange filed by 91 people who said they were victims of church-based sexual abuse. Casteix could have taken her share and quietly moved on. Instead, she has dedicated her life to her cause. She is the western regional director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, an international nonprofit organization based in Chicago. She also works with other advocacy and research groups, and has become one of the nation's most visible faces on the topic of child sexual abuse.

Working from the small, toy-filled condo she shares with her husband and 4-year-old son, Casteix spends her days writing letters and news releases, handing out leaflets, talking to the media, doing research, planning public information campaigns, and responding to calls and e-mails from those who have been abused. She has been interviewed on CNN. She spends her own money to travel throughout the country and abroad to testify in favor of strengthening laws against sexual predators, to protest church appointments of suspected pedophiles, and to alert communities about accused sexual predators among them. In June, she traveled to Europe with two other SNAP representatives to organize support groups, and to protest in Rome against what they contend is an inadequate response from the Vatican to the church's sexual abuse crisis.

In return for her efforts, Casteix is sometimes vilified as a church-hating gadfly. She has been pushed, poked, yelled at, and accused of seeking only money and fame. After Casteix was quoted in the Los Angeles Times last September criticizing defenders of Roman Polanski, the film director who fled the United States more than 30 years ago to avoid being sentenced for having sex with a 13-year-old girl, one e-mail respondent on the newspaper's website wrote of being "tired" of groups such as SNAP using individual cases "for their personal agenda."

Last April, after Casteix and other SNAP members distributed fliers at a Santa Clarita church alerting parishioners that their new pastor had been accused of child molestation, an online reply to a local newspaper's account of the event complained: "All it takes today to destroy someone is to simply ACCUSE them of something." On a recent trip to Guam to meet alleged molestation victims and urge church officials there to openly discuss sexual abuse claims, Casteix says she received vaguely menacing e-mails warning her to "watch your back."

|

Closer to home, Casteix has sparred with conservative Orange County blogger and consultant Matt Cunningham, whom she views as an "apologist" for church officials who conceal abuse. In an online posting, Casteix wrote that she "can do little more than fear for Mr. Cunningham's children. Anyone who defends molesters, outs victims, criticizes survivors who dare to demand accountability, and lives in a complete and utter denial is feeding his children to the wolves." Cunningham later called Casteix's remark a "thoughtless, idiotic comment."

Casteix has been particularly unsparing in her criticism of the Diocese of Orange, which she says has failed to deliver on its pledge of greater openness and accountability made at the time of the 2005 settlement. In reply to questions about Casteix and her assertions, diocese spokesman Ryan Lilyengren provided a written statement in which he maintained that Bishop Brown is known as "a progressive church leader," and that his "bold initiative to settle past clergy abuse cases in Orange in a respectful and humble manner has been seen as a model for others."

Nonetheless, Casteix has many supporters who say she's one of the biggest catalysts for progress on the issue of child molestation. Terry McKiernan, founder of BishopAccountability.org, which tracks church-based sexual abuse cases, calls Casteix a leader and a visionary in the victims' rights movement. "I'm convinced she's helped thousands of people," he says. "She's also modeling the kind of person that survivors can become."

Numbers on child molestation are difficult to calculate, in large part because it's widely thought to be one of the most underreported crimes. While there's no direct evidence that the problem is more prevalent within church-based institutions, critics charge that the Catholic Church's long history of cover-ups has allowed molesters in its ranks-both clergy and lay personnel-to continue abusing children with impunity.

Revelations of possible church cover-ups surface almost daily. Once viewed as a problem confined to the United States, the scandal has spread throughout Europe, Mexico, and South America, and recently landed on the doorstep of the Vatican itself. A lawsuit stemming from alleged abuse by priests in Kentucky claims that the Vatican instructed U.S. bishops to keep quiet about claims. Questions also have been raised about Pope Benedict XVI's possible pre-papal role in covering up for molesters, including reports this year in the German press that he authorized the 1980 transfer of an abusive priest who was later convicted of subsequent sexual assaults.

All of which makes Casteix even more determined to speak out. "I think we're on this groundswell of awareness," she says. "The more child sexual abuse is a crime of shame and secrecy, the more it's allowed to propagate. We need to make it part of our everyday conversations. It's something we have the power to control and stop."

Raised in Santa Ana, Casteix's childhood was steeped in Roman Catholic tradition. Her grandfather was an Orange County deputy coroner in the late 1930s and early '40s, and her grandmother was a clerk for the county Board of Supervisors. They sent their son-Casteix's father-to Mater Dei, the Catholic high school in Santa Ana best known as a sports powerhouse. Some of Casteix's earliest memories are of cheering for the Monarchs at football games; there was never any doubt she also would one day attend the school.

At Mater Dei, she was an A student, a member of school's elite touring choir, and appeared on track for success. But Casteix back then was struggling with the complications of an often unhappy childhood. Her mother was an alcoholic whose tirades took their toll on the sensitive girl. With her older sister away at college and her father busy at work, Casteix fell into a deep depression. When she was 15, she went into her garage, put a rope around her neck and tried to hang herself in what she now calls "a pretty feeble cry for help." Casteix was hospitalized for several weeks under an involuntary psychiatric hold, while at the same time her mother entered the first of several stints in rehab.

After Casteix returned to school, she met the new choir director. "He was young, early 30s, everyone liked him-he was cool," she says. "He apparently had been briefed about me, that I was vulnerable. He zeroed in on me right away, and instantly started grooming me."

According to Casteix, the teacher slowly began pushing the boundaries, at first talking to her at length and showing concern, then offering her rides home and sharing intimate details about his sex life. His touches became caresses. At first, Casteix was flattered. "He said he cared. He said he understood me. I was just so happy that an adult cared." But when the touching escalated to intercourse, Casteix says, "I knew something was terribly wrong."

Casteix says she sought help from a school administrator, who told her she was in "an adult relationship," but warned her not to talk to other adults about it because they wouldn't understand and she'd be sent back to the hospital. Casteix says the relationship with the teacher continued through her senior year, and that he "threatened to fail me if I didn't do what he wanted." In 1988, shortly after graduation, she discovered she was pregnant, and had genital warts, which are caused by a virus transmitted through intercourse. At 17, she had an abortion.

Casteix headed off to UC Santa Barbara, where she majored in opera and English. Yet she remained wracked by guilt and shame. She hadn't confided in her parents about her history, in part because she accepted their view that rape occurred only when a victim was physically overpowered. But in the fall of 1989, during her sophomore year, she wrote a column for the student newspaper marking the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade court decision legalizing abortion. In it, Casteix acknowledged her earlier pregnancy and abortion, and identified the father as one of her high school teachers. She wrote that she "was not raped," and that "it was my stupidity and my ignorance that got me into this situation"-beliefs she now says were fed by her confusion and self-recrimination at the time. Other former Mater Dei students brought the article to the attention of the high school's administration. The teacher resigned in November 1989. No charges were filed. Casteix says her parents, finally aware of their daughter's history with her former teacher, blamed her for the mess.

Casteix tried to move on with her life, but says that in her 20s she went through a period of rampant promiscuity-behavior common among sexual abuse victims. An early marriage didn't work out. She moved to Colorado, then to the Palm Springs area, working at times as a journalist, a public relations specialist, and a media consultant. She moved back to Orange County in 2000, remarried in 2004, and, after years of therapy, she says, began to heal.

"By the time I finally realized that it wasn't my fault, the criminal statute had lapsed," Casteix says. "There was nothing I could do about it."

By the early 2000s, however, things had begun to change. The church scandal was becoming national news, first in Boston, then in parishes across the country. In Orange County in 2001, the diocese agreed to pay Ryan DiMaria $5.2 million, the largest publicly disclosed settlement paid to an individual by the church. DiMaria said he was molested by Msgr. Michael A. Harris, a former principal at Mater Dei and at Santa Margarita Catholic High School in Rancho Santa Margarita. Harris denies the allegations and was never criminally charged, despite similar claims by other former students. He was placed on inactive leave in 1994 and agreed to formally leave the priesthood as part of the 2001 settlement.

Casteix had other reasons to hope. Though her mother had since died, her once-disapproving father had become more supportive after he married a woman who sympathized with Casteix. And, in 2002, after Casteix had written to Mater Dei administrators offering to help them implement a zero-tolerance policy for sexual misconduct, she agreed to serve on a lay committee started by the Diocese of Orange to review sexual abuse claims. But she says that after several months of attending meetings at which no caseswere reviewed, no minutes were written, and no actions were taken, she quit in frustration.

That was in 2003, a year that marked a turning point for victims of sexual abuse in California. The state had passed a law that suspended, for one year, the statute of limitations on civil cases against institutions accused of failing to protect abused children. The phone began ringing regularly at the Newport Beach office of John C. Manly, one of the lawyers who had represented DiMaria. Casteix was among those callers.

Manly says that when he first met Casteix, she was still unsure about pursuing litigation, but in time she grew stronger in her conviction that she needed to fight for justice. "For her, filing that claim-she got her life back," he says.

California's one-year civil window resulted in some of the nation's largest settlements of sexual abuse claims against the church. The $100 million Orange County settlement was followed a few years later by settlements of $660 million in the Los Angeles Archdiocese and $198 million in San Diego and San Bernardino dioceses. BishopAccountability.org estimates that more than $3 billion in church-based settlements have been reached in the United States alone.

The Orange County case has been singled out for praise by victims' rights advocates because the settlement included church documents related to 15 priests and teachers accused of molestation. The documents showed that the diocese shielded known and suspected predators, often moving them from parish to parish without warning parishioners. For example, church officials shipped one serial molester to a parish in Tijuana; accepted a convicted child abuser from an out-of-state parish who allegedly continued to molest children while at churches in Anaheim and Yorba Linda; and offered to pay another known molester to quietly leave the priesthood.

Casteix's persistence during settlement talks was one of the main forces behind the disclosures, says McKiernan of BishopAccountability.org. "She made it clear that the documents had to be a part of it. What she has been able to do is just so remarkable."

In a strange twist, however, the documents relating to Casteix's own case were not included in the settlement because her former teacher had filed an objection to block their release, as the law allowed. Casteix describes the day she learned she wouldn't have access to the paperwork as one of the worst of her life. She says she was about to hunker down for a long cry, with a carton of ice cream as solace, when she found out that the records for her case had accidentally been included among the other documents that had been made public.

Among those documents was a copy of a memo on Mater Dei letterhead indicating that 1? years before he resigned, Casteix's music teacher had admitted to a high school administrator that he'd had sex with Casteix. Another letter stated that the teacher also had admitted to having sex with another student. Emboldened by the revelations, Casteix traveled to Michigan, where her former teacher now works at a liberal arts college associated with the United Methodist Church, to inform school officials of his past. She says they were not interested in her information.

Confronting alleged molesters and the institutions accused of sheltering them isn't the sole focus of Casteix's advocacy work. Another priority, she says, is the passage of more victim-friendly laws. David Clohessy, SNAP's executive director, recalls watching Casteix's passionate testimony a few years ago before the Ohio General Assembly in favor of changing the state's statute of limitations for sexual abuse claims. As Casteix told her story, he says, "you could literally hear a pin drop in that room. It was heart-wrenching testimony. They were riveted." Nonetheless, the bill was defeated.

Equally important, Casteix says, is creating an environment in which victims aren't afraid to come forward, and aren't tortured by the mistaken idea that they were complicit in their own abuse. She has earned the gratitude of abuse survivors who say her support helped them go public with their stories. Among them is Elaina Kroll of Newport Beach, one of four women who reached a nearly $6.7 million settlement with the Diocese of Orange in 2007. When she was in high school, Kroll was abused by the music director at a Catholic parish in Laguna Niguel. The music director pleaded guilty in 2009 to sexual molestation, was sentenced to five years' probation, and was required to register as a sex offender. Casteix has "been there every step of the way for me," says Kroll. Her support "was pivotal. It empowered me."

Kroll last year formed a nonprofit advocacy group of her own, The Innocence Mission, hoping to deter child molestation by educating children, parents, and educators about the issue. Casteix is its vice president.

Can child sexual abuse be eliminated? It's a tall order, and Casteix knows it. "In my generation, will we do it? No," she says. "But in my generation, we're going to get rid of the cover-up."

As she patiently approaches churchgoers in front of St. Angela Merici, Casteix acknowledges that most of the fliers she has handed out will be cast aside. But she says that efforts like this invariably result in a phone call or e-mail from someone who may have been molested, who suspects abuse, or who simply wants to help-and that's what keeps her going. It's the twig in the forest, and she'll take that-for now. God may be omnipresent, but Casteix knows that lowly mortals need to keep a watchful eye.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.