By Melissa Musick Nussbaum and L. Martin Nussbaum

First Things

December 10, 2010

http://www.firstthings.com/onthesquare/2010/12/ldquothe-american-river-gangesrdquo-rising

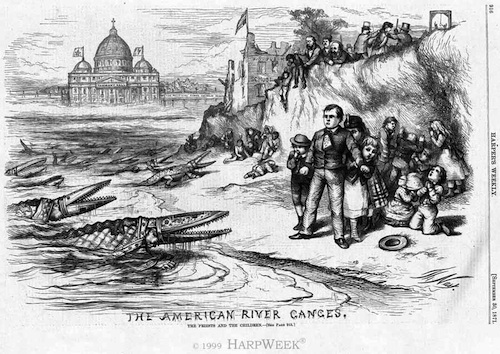

The cartoon below appeared, with an accompanying article, in Harper’s magazine. The article is entitled “The Priests and the Children.” The cartoon shows a group of children huddled behind a single adult protector along the banks of a river. The children are weeping. Some are down on their knees in supplication. Some are peeking out from behind their lone defender’s back. All of them look fearful.

|

The children are trapped on the shore as strange reptile-human hybrids emerge from the water. They are Roman Catholic bishops, crawling onto land with stubby legs; their vestments stippled like alligator hide. Their miters are maws, opening to reveal a double row of sharp teeth dripping with water—or, perhaps, blood. Above each gaping snout, a single jeweled eye shines, alive, but not human. The faces of the bishops beneath the mouth-miters are not, however, reptilian, but simian. Their features are dark and heavy, their brows low. The cartoon suggest that these monsters have come to devour the children.

When do you think this editorial cartoon and its accompanying article appeared? In 2002, when the articles and cartoons about the Catholic sex abuse crisis reached a crescendo? They are, rather, from the September 30, 1871 issue of Harper’s. Thomas Nast drew the cartoon. Eugene Lawrence wrote the article, addressing the threat to America’s children posed by the establishment and support of Catholic schools in New York City.

“To destroy our free schools, and perhaps our free institutions, has been for many years the constant aim of the extreme section of the Romish Church,” Lawrence wrote in his article. Romish and, in particular, Jesuit, influence on New York’s school system—as Catholic (read: Irish) politicians came to sit on school boards and other city councils—had already lead to alarming results: “They [Catholics] required that the Bible should be wholly disused in popular education. . . . And in several Catholic schools the Bible has never been read for twenty years.” Additionally, “The Protestant teacher was often made to feel the impertinences of his ignorant masters.”

The effects of an entirely separate, Romish-controlled school system, Lawrence warns, would be catastrophic:

“Our treasury rifled; our credit shaken; the poor laborer asking vainly for his honest wages day after day; the rich official reveling in disreputable gains; an enormous debt heaped upon us we know not how; our schools decaying, our teachers cowering before their Catholic masters; our press, when it ventures to complain, threatened with violence or insulted by offered bribes; the interests of the city neglected, its honorable reputation gone.”

With the exception of the charge that Catholics do not allow the teaching of the Bible in school, the critique has nothing to do with curriculum or method. The critique is of foreign corruption and ignorance, of secret dealings among the keepers of a secret rite, of financial ruin and social collapse, of bullies and the hapless bullied mob.

Nast needs few words; his sketch is a nightmare in pen and ink. There is only this caption, “The American River Ganges,” suggesting not only the foreign, but a land so distant from most Americans as to be wholly other, completely alien. In his book, American Catholic: the Saints and Sinners Who Built America’s Most Powerful Church, historian Charles R. Morris calls “The American River Ganges,” “Perhaps the most brilliantly poisonous of Thomas Nast’s popular anti-Catholic cartoons.”

Nast and Lawrence were not alone in their fear of “the Romish Church.” In 1834, a young woman named Rebecca Reed published Six Months in a Convent, her account of sexual deviancy at an Ursuline convent in Charleston, Massachusetts from which she claimed to have escaped.

On August 10, 1834, famous Congregationalist pastor, Lyman Beecher, the father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, preached a sermon entitled “The Devil and the Pope of Rome,” in which he singled out the Ursuline sisters of Charleston. The next day, a mob attacked the Ursuline convent.

In his book, Morris describes the August 11 attack. After being told by a “formidable woman” who “met them at the gate” to disperse or she would have the bishop summon “twenty thousand Irishmen at his command in Boston,” they stormed the gate, “rampaging from room to room, smashing furniture and china, and setting the rooms on fire. Drunken rowdies put on nuns' habits and danced lewdly around bonfires of books and furniture.” The fire company arrived but did not intervene. The nuns and the novices escaped through the back gate, running for their lives. The mob then spread through Charlestown, attacking and burning a number of Irish homes.

Books about sexual deviancy among Catholic priests and nuns were popular in the nineteenth century. Maria Monk, published her Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Convent of Montreal, or The Secrets of the Black Nunnery Revealed in 1836. Morris estimates it sold 300,000 copies before the Civil War. “It has been called the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of anti-Catholicism,” Morris writes, “or the anti-Catholic equivalent of the anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, not so long ago thought to be permanently discredited, is now enjoying a resurgence of popularity, particularly in Islamic countries. Like the threatening images of the Protocols, the images of foreign, secretive, power hungry, and sexually deviant Catholic cabals go underground in some decades, only to re-emerge in others.

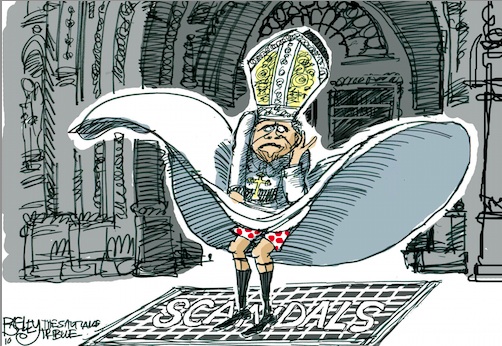

One hundred and twenty years later, the cartoons of reptile-human hybrids, bishops on the hunt for America’s children, have reappeared. Nast’s trope of the alien, not quite human, Catholic has come out of hibernation to be printed in newspapers and magazines all over the United States and the world.

|

The 1871 cartoon and article were published as a warning against the establishment of a Catholic school system in New York City. Gerald Scarfe’s 2009 cartoon suggests those fears were prescient. The cartoon shows a ghostly cassock-clad priest. Flame-like streaks of yellow climb from the hem of his cassock. His eyes are lidded in the same burning yellow. His hands are claws. Beneath a full moon, he stands, ready to push open a door marked “Boys’ Dormitory.”

In 2002, Paul Conrad depicted “St. Pedophile’s” Catholic Church, with the caption, “Suffer the little children to come unto me.” Conrad joins many other cartoonists in using the name “St. Pedophilia’s Church,” or a variant of it, for their work.

The cartoonist publishing under the moniker Signe drew a 2002 cartoon in which a priest, dressed in clerical blacks and white Roman collar, sits on a cot behind bars. The caption reads, “CELL-IBATE.” In another cartoon—which appeared in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune—the Roman collar is shown floating above a metal chastity belt.

A favorite trope remains Nast’s bishop’s miter, transformed into reptilian jaws. A variation on that theme shows Pope Benedict XVI wearing his tooth-lined miter. Or another which depicts a leering priest and a howling child emerging from the top of the pope’s miter. The miter is squashed low on Benedict’s forehead, giving him a simian appearance. Beneath the picture is Benedict’s “question.” “Did I ever tell you I was a member of the Hitler Youth?”

Another favored theme is the vestment itself, suggesting that, underneath its folds, dangerous and deviant acts are at work. In Gerald Scarfe’s cartoon of 2010, the unnamed episcopal figure is a grinning skeleton. In one dead hand he holds a crucifix, on which is hung the body of a child. Beneath his skirts, three damned priests, one drawn with devil horns and pointed ears, clutch their screaming victims, all boys. The scrawled caption reads, “HELL.”

In Milt Priggee’s 2004 cartoon, an unnamed bishop strides forward, smoke from his censor rising just above the devil’s tail snaking out from underneath his vestments. In another Prigee cartoon a mitered and vested bishop is face to face with the devil. Standing amidst the fires of hell, the devil says, “Funny meeting you here.” The bishop, his eyes covered by the miter, responds, “Not really.”

|

Some might argue that nativist hysteria is quite a different thing from the revelation of the real menace of priest perpetrators. But consider this snapshot of the sexual abuse of children in the United States: the 2009 Annual Report prepared for the Catholic bishops by an independent auditor identifies an average of 21 allegations of childhood sexual abuse per year in the American Catholic Church for the current decade, with this number dropping to six allegations in 2009. The 2007 Associated Press investigation identifies 2570 public school teachers who, from 2001 through 2005, had their teaching licenses “taken away, denied, surrendered voluntarily, or restricted” as a result of sexual misconduct with minors—an average of 514 per year. If the flood of hateful cartoons is a response to a true threat, where are the cartoons featuring first grade teachers, their incisors dripping blood, their clawed hands reaching for the cowering children?

Images of a “foreign” faith and its medieval accouterments continues to alarm the American public. And newspapers, far from being silenced by threats of violence or bribes as Lawrence suspected they would be, continue to provide outlets for these vile images. The American River Ganges still rises, its current fed by the runoff of ignorance and fear.

Melissa Musick Nussbaum is a columnist for the National Catholic Reporter and the author of six books and numerous articles. L. Martin Nussbaum is an attorney who advocates on behalf of religious institutions nationwide. They have been married for thirty-six years.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.