Eureka Street

March 24, 2011

http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=25417

|

To all intents and purposes it looked like an email requesting supervision for a research proposal. Nothing unusual in that. I get a steady trickle of these. There was an attached letter which I opened, and immediately knew much more was at stake.

The communication was from a student I had had discussions with over ten years ago about a possible research topic. Without warning or further communication he vanished. Now he was about to open the door of his heart to reveal the reasons for his disappearance.

It was the sort of story I had heard often before when my wife and I were involved with the issue of clergy sexual abuse. It was a story of seduction, manipulation, violation and psychological damage.

In training for the priesthood this young man had been abused by a senior and much older seminarian, in whose pastoral care he had been placed. The seduction and manipulation extended to the young man's family and church community.

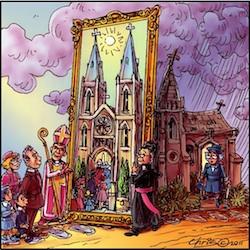

While the older seminarian went on to ordination, a position of trust and responsibility in the Church, the younger man's life fell into a spiral of self-destructive behaviours, symptomatic of post-traumatic stress. While the abuser is an honoured member of the Church community, the victim has been shunned by his family and church community. What's wrong with this picture!

The response of Church authorities has been less than inspiring. On advice the victim sought to contact the diocesan professional standards team. Each time he rang (some 20 times) he received a recorded message.

Try to imagine the leap of trust required to contact the Church to report abuse; the degree of agitation involved in drumming up the courage to tell one's story to those who represent the authorities of the very institution that abused you. And then to receive a recorded message — leave your details and we'll ring you back. This is not malicious, but it is a benign ineptitude, a stunning lack in moral imagination.

The sad thing is how little has changed since our original involvement some 15 years ago. Yes, documents and policies have been put in place; apologies have been expressed publicly and promises of doing better have been expressed. Even some degree of moral outrage: 'This must not happen again!' But in the end, not much has changed. Indeed it is still more of the same.

The problem is systemic. Not in the sense that the system produces abuse — abuse occurs within all sorts of institutional and familial settings. But the system has no intelligent and responsible way of dealing with the abuse that occurs. From Church authorities down to the local community there is simply an inability to enter into the perspective of the victim of abuse.

Like the priests and Levites in the parable of the Good Samaritan, it is easier to walk past on the other side than hear the cries of betrayed trust and mental anguish that arise. And this betrayal touches the religious identity of its victim. The one who was supposed to speak to them of God's love and forgiveness, his grace and mercy, has sexually abused them.

This systemic problem shows how badly the Church has failed in its own terms. The Church is supposed to know about sin and grace, repentance and conversion, penance and reparation, healing and mercy. These are part of its core business. A pope once said the Church is an expert in humanity. These problems are the stuff of our human condition, yet the Church's response is fumbling at best. Not much expertise on display here.

I have long felt that the major cause of this lack of institutional response lies with the spontaneous identification of priests and bishops with the perpetrator of abuse. They are all members of the same club. They all had the same formation experiences, live with the same stresses and strains, and have the same temptations.

One priest on hearing from a victim of a fellow priest's repeated sexualising of his pastoral relations with various young women cried out, 'The poor man, struggling with his celibacy'. No sense at all of the trail of destruction caused and the faith damaged. Immediately it became a problem of personal spirituality, narcissistically appropriated, 'poor me/him'; not anger at the spiritual violation of another person.

I cannot recall ever hearing a priest express anger at the actions of an abusive priest (except perhaps Geoffrey Robinson), and the damage they do to their victims, as well as to their own ministry as the trust of the community towards all priests evaporates. Rather, what I pick up is a sense of shame and tacit complicity. Shame is disempowering.

When I was a child our parish priest wore a badge indicating his membership of a priestly fellowship called the Pioneers. These priests made a solemn promise not to drink alcohol. We need such a fellowship today, of priests who make a solemn promise not to sexually abuse or exploit those in their pastoral care, a network of support and solidarity, of counsel and prayer.

Perhaps the Church should suspend all homilies for a month and sit in silent prayer for the healing of the victims of abuse and the conversion and repentance of their abusers; to help make our church communities safer places for victims to be present.

In the time they save from writing homilies, priests and bishops could develop a searching moral inventory (to borrow from Twelve Step programs) of their own failures to deal with this problem, their lack of leadership in their communities to make them safe, and the positive steps they can take to repair the damage that has been done to individuals and communities.

Something more than platitudes are needed. The Church is dying on the vine, and tinkering with liturgies and translations is not going to bring it back to life. Its credibility is shot to pieces every time abuse occurs.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.