By Andrew Hamilton

Eureka Street

May 4, 2011

http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=26166

|

The forced retirement of Bishop Bill Morris raises many questions.

Some questions concern the facts of the case — why the Bishop's pastoral strategies and his reflections on ways of addressing the shortage of priests in rural dioceses were found to be inconsistent with Catholic values. These questions cannot be usefully discussed because the evidence against him and the evaluation made of it have not been publicly disclosed.

Even more significant questions concern the process that culminated in his retirement. An understated paragraph of the pastoral letter in which Bishop Morris communicated to the Toowoomba Church his decision to take early retirement raises the question sharply. He says:

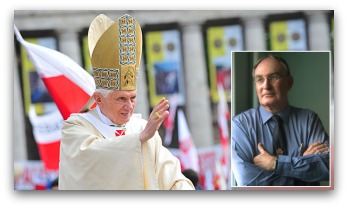

I have never seen the Report prepared by the Apostolic Visitor, Archbishop Charles Chaput, and without due process it has been impossible to resolve these matters, denying me natural justice without any possibility of appropriate defence and advocacy on my behalf. Pope Benedict confirmed this to me by stating 'Canon Law does not make provision for a process regarding bishops, whom the Successor of Peter nominates and may remove from Office'.

Outside observers used to the English legal system are likely to see this lack of due process and of natural justice as scandalous. They would notice the parallel with the non-statutory process by which asylum seekers on Nauru had the claims for protection assessed. It resulted in a morass of arbitrariness, and was experienced by its victims as abusive of their human dignity. In Australia, it is the case that where there is no statutory review there can be no confidence in justice.

Of course the legal system of the Catholic Church is not based on English law. It goes back a long way further than that. So it may offer assurances of justice that the outside observer might miss. But the gap makes even Catholic observers ask why the Pope should see the denial of due process as demanded by his position. And they might also muse whether the received Catholic understanding of the papacy must really exclude due process.

To understand the Pope's claim, you need to go back to the Gospels. The place of the papacy in the Church is based on the position of Peter among the 12 disciples whom Jesus chose. The Bishop of Rome is understood to stand in the same relationship to the other Bishops as did Peter to the Twelve. Peter is one of the Twelve, but is given by Christ a primacy among them. He is to strengthen his brothers in living and preaching the Gospel.

Encouraging others in faith naturally included the soft means of encouragement and example. But it has also embraced the hard responsibility to resolve disputes about faith and order when asked to do so, and also uninvited when necessary.

The analogy between the Pope and Peter suggests that the powers of the Pope are personal to him, and do not depend on the consent of the other bishops.

Over the centuries attempts were made to limit papal power by subordinating it to imperial power, to the authority of Church Councils and to the consent of other bishops. These limitations were successfully opposed on the grounds that they minimised the commission that Christ gave to Peter, and so to the Pope, to strengthen the unity in faith of the universal church.

Pope Benedict's statement that he may name and remove bishops without judicial process reflects this long defence of papal primacy in the Western Church. The personal character of Peter's powers means the Pope is not subject to church law when exercising them. This view is adamantine. Such is the volume of water that has gone under this bridge that we are unlikely to see it flowing back again.

But even if the right of the Pope to remove bishops in extraordinary circumstances is conceded, it remains in both his interests and those of the Church he serves that this be done in ways which encourage unity in faith. Such encouragement will increase or diminish according to the extent to which Catholics are confident that the Pope exercises his powers wisely and responsibly.

Confidence in any governance, including that of the Church, is weakened where there is a lack of transparency and of due process in the making of decisions that cause harm to people. Lack of accountability injures the human dignity of the people affected. Confidence grows when there is due accountability.

In received Catholic theology, the Pope is directly accountable only to God when he acts to strengthen the faith and order of the universal church. But that is perfectly compatible with a process within which his final decision is made only after a review of the reports and recommendations made by his officers. The person whose future rests on the decision should have the right to see the report and evidence upon which it is based, and to argue his case. The review of the case would thus contribute to the Pope's final decision, and not overturn a decision already made.

Modern societies rightly put much weight on transparency. Its absence is taken to discredit the institutions in which it is lacking. After the forced resignation of Bishop Morris it will be even harder for Catholics to win a hearing on issues that affect the public order.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.