By Max Lindenman

The Patheos

June 5, 2011

http://www.patheos.com/Resources/Additional-Resources/Fr-Shawn-Ratigan-Catching-a-Creep-in-the-Circle-of-Grace-Max-Lindenman-06-06-2011.html

|

Fr. Shawn Ratigan, pastor of St. Patrick's, an elementary school in the diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, must have presented parents and faculty with a Hitchcockian conundrum. His behavior toward children was clearly creepy. Here, I'm borrowing the word of an eighth-grade girl—who sensibly rejected his Facebook friendship request—because, really, there's none better. Ratigan encouraged children to sit on his lap and dig in his pockets for candy. He photographed them constantly—even, observers noted, when they weren't doing anything especially photogenic. He coaxed one boy into his office; when asked why, the boy explained, "He said he wanted to show me something."

Creepy is one thing. The question remained: was Ratigan's behavior criminal? Based on the evidence available at the time, nobody could have said in good conscience that it was.

Anyone who's followed Michael Jackson's career should know the drill. Some adult displays an attitude toward children that's plainly abnormal. With cunning, good luck, or even a modicum of self-control, he manages to deny the world proof that his abnormality has reached actionable proportions. Short of seizing torch and pitchfork, onlookers have no choice but to watch and wait.

It was in the watching and the waiting that the staff and parents of St. Patrick's transformed passivity into activity. They compared notes on Ratigan's behavior, corroborated one another's impressions, and checked those against expert opinion. Thanks to their vigilance, Julie Hess, St. Patrick's principal, was able to fuse a mosaic of apparent non-events into a coherent picture of pathology. In May of 2010, she reproduced this picture in a 28-paragraph report (pdf), which she sent off to the diocese.

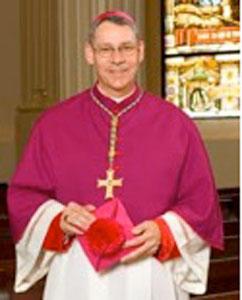

The story has been in the national media for a couple of weeks already, and the bulk of the attention has gone to the response of Bishop Robert Finn. Ignoring Hess's report, he sat on a summary given him by Msgr. Robert Murphy, his Vicar General, until several months later, when he learned that Ratigan possessed pornographic images of children. Even then, he declined to inform police for several more months until Ratigan violated his orders by consorting with minors. By pre-2002 standards, it was a B+ performance; by today's, a D.

But boos for Finn should not, I don't think, drown out the applause due the other actors in this drama. Watchdogging Ratigan can't have been an easy task. To the very end, he had his supporters. He had served as a spokesman for the Catholic Boy Scouts. Even after he'd been removed as pastor of St. Patrick's, at least one set of parents requested his presence at their child's birthday party.

Facing criticism, Ratigan could be highly manipulative. When a teacher tried to interpose herself between Fr. Ratigan and a fifth-grade girl, he complained to her colleague about being undeservingly suspected by "a teacher who's not even Catholic." Yes, that's right—he played the closest thing he had to the race card.

That quote from Ratigan makes up just one line in Hess's report, but it points, I think, toward an even thicker bramble bush. According to National Catholic Reporter, Finn's recent elevation as bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph preceded an "extreme makeover" for the diocese. This included not only a grand personnel shake-up but a shift in emphasis from "social engagement and lay empowerment" to "Catholic identity and evangelization." With fault lines visible, Fr. Ratigan might have thought he'd picked a better time to complain about being ganged up on.

In fact, it has become popular in certain Catholic circles to brand the whole notion of endemic sex abuse as a Big Lie. In Crisis Magazine, Rev. Robert Orsi disparages the 2002 Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, claiming its "one-size-fits-all approach" to allegations of abuse has "left every innocent priest vulnerable to defamation and dismissal from the ministry." In support of that statement, Orsi cites "a retired FBI agent" who had worked with him, investigating abuse charges, to the effect that "about ONE-HALF of the claims made in the Clergy Cases were either entirely false or so greatly exaggerated."

The capital letters are Orsi's, and so was the decision to use an anonymous source in justifying such an extravagant claim. I can't believe he'd have made such a decision—or that his editors would have okayed it—unless the claim confirmed what many readers regard as a self-evident truth. For Julie Hess and the St. Pat's parents to say what they said, in the face of so fierce a backlash, was to toss their reputations to the wind.

In fairness to the skeptics, few longstanding critics of Church discipline have been willing to let the priestly pedophilia crisis go to waste. Women priests, married priests, changes in the theology of the priesthood—all have been proposed, either explicitly as cure-alls, or as salutary climate-changers. If nobody has fabricated the endemic quality of the abuse, no shortage of people has milked it. To make any statement about abusive priests without making a more sweeping one about theology or ecclesiology is nearly impossible. I wouldn't venture a guess how many people really want to try.

Taken together, all of these difficulties—in characterizing certain behaviors, in finding a disinterested accuser or a fair-minded judge—prove the good sense behind the diocesan child safety guidelines. In her report, Hess refers constantly to the Circle of Grace (pdf). Though this term for physical and emotional boundaries was coined for kids in the awareness training program borrowed from the diocese of Omaha, it seems to have entered the vocabulary of the St. Pat's adults. Small wonder—the idea of a magic circle of inviolability is a catchy one, recalling my mother's stories of nuns who would remind slow-dancing couples to "leave room for the Holy Ghost." It enlivens the language of the diocesan ethical code, which discourages adults from "physical contact with youth beyond a handshake."

In whatever terms, the standards are objective, in the best tradition of Catholic moral theology. This also makes them non-partisan. It imposes the same restrictions on Pax Christi members as on Knights of Columbus chaplains.

Whether the notion of the Circle of Grace enhanced the street smarts of the St. Pat's adults in any appreciable way I don't know; ours is a sophisticated generation. But I would bet that the clarity of the guidelines served to quiet that caviling inner voice that says, "Don't be such a paranoid loon." They might not teach vigilance, but they validate it. In Ratigan's case, that was enough.

From some angles, the conduct code looks like a micromanager's dream. But child protection may be the one instance where small acts of disobedience really can signify major character flaws. Several people, including Principal Hess, reminded Ratigan of the rules in what seems to have been a non-accusatory tone; Ratigan protested and blustered, raising staff suspicions even higher. It was as if, for once, the devil really did give himself away by a faint whiff of sulfur.

Stories about bad or careless bishops have been so numerous; I can barely stand to hear any more. They're numbing me into complacency. The same stories enrage other Catholics into denial, which is worse. So let's flip the script for a second, and focus instead on the splendid tools that run the risk of going unused. In every diocese, we've got guidelines that can smoke out potential abusers before they do too much harm; at the grassroots level, we've got adults willing to face awkwardness and disappointment in order to enforce them. Doesn't that make you feel better?

No? Me neither. But it makes me mad in new and exciting way. That should count for something.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.