By Grant Gallicho

Religion Dispatchesv

June 15, 2011

http://www.religiondispatches.org/archive/atheologies/4750/too_late_for_apologies%3A_three_steps_the_u.s._bishops_should_take_to_prevent_another_sexual_abuse_scandal

|

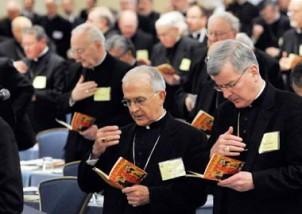

| U.S. Bishops at a meeting in Baltimore |

This week, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops is holding its annual summer meeting in Seattle (to be live-streamed, starting Wednesday, June 15). The bishops will take up a number of issues, from the revised liturgy to assisted suicide, but their conversations are sure to be dominated by an issue that has been dogging them since the mid-1980s: sexually abusive priests and the bishops who enabled them. Ten years after Cardinal Bernard Law became the poster bishop for failed religious leadership, new revelations of episcopal misfeasance threaten to swamp the real gains made by the Church.

One Step Forward...

In the summer of 2002, the bishops adopted stricter rules for handling abuse allegations. They agreed to a set of guidelines called the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People that would govern their response to accusations (several of the Charter's provisions were approved by the Vatican as canon law for U.S. dioceses). The Charter called for dioceses to cooperate with civil authorities and comply with reporting laws, to permanently remove abuser-priests from ministry, and to establish majority-lay review boards to look at allegations against clergy and advise bishops whether to suspend the accused.

The bishops also required priests, deacons, diocesan employees, volunteers, and children in education programs to undergo "safe environment" training. The Charter has gone a long way toward addressing the crisis. Last month, the bishops released a study of the "causes and context" of the crisis, conducted by independent researchers from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The report shows that abuse allegations have been steadily declining since the 1980s. Even so, the most recent diocesan audits found just seven credible allegations of abuse in 2010. In 1975, according to the John Jay report, there were more than 300 incidents of abuse.

Still, over the past several months, dangerous weaknesses in the Charter have become painfully clear. In February, a Philadelphia grand jury found "substantial evidence" of abuse committed by thirty-seven priests in active ministry. Cardinal Justin Rigali, after initially claiming that there were no "admitted" or "confirmed" abusers in ministry, subsequently suspended twenty-seven clerics. And in May, the chair of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia review board revealed that the archdiocese had been keeping cases of accused priests from the board. Of the thirty-seven priests identified by the grand-jury report, the board had reviewed the cases of just ten. The cardinal eventually apologized.

Last month it came to light that in May 2010 the principal of a Catholic elementary school had warned the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph that a priest "fit the profile of a child predator," and the diocese didn't take action against the priest for six months. Fr. Shawn Ratigan was arrested a few weeks ago on three counts of possessing child pornography. The diocesan review board never saw the case. Bishop Robert Finn eventually apologized.

These recent developments should not have been a surprise. In October 2005—just three years after the bishops' adopted their new norms—the Archdiocese of Chicago's review board recommended removing an accused priest, Daniel McCormack, from ministry, and Cardinal Francis George refused to do so. He wasn't removed from ministry until January 2006, and McCormack later pled guilty to abusing five kids. As the victims' attorney Marc Pearlman told NPR, "I just don't know… how many kids were abused between the fall of 2005 and January of 2006, when he was finally removed." The cardinal eventually apologized.

At this late date, apologies are not enough. The reason the U.S. bishops adopted rules requiring dioceses to have review boards is that bishops couldn't be trusted to handle the problem on their own. Yet the Charter simply mandates that dioceses establish review boards; it doesn't say how they should work. And, as the egregious lapses in Philadelphia and elsewhere show, it's not clear that they are working.

Steps to Take

How might the bishops fix what's broken when they meet this week?

First, improve communication. Diocesan review boards are sometimes in touch with the National Review Board, which oversees the implementation of the Charter. But there is very little information sharing between local review boards. Why not hold an annual meeting of diocesan review board chairs, conducted by the National Review Board, where participants could share best practices?

In addition, bishops need to meet with their review boards on a regular basis. Many bishops do, but not all. In the Diocese of Gallup, New Mexico, for example, the chair of the review board recently admitted that the bishop has never met with the board. The relationship between a review board and the bishop should not be adversarial or distant. Review boards are meant to help a bishop do his job.

Second, standardize review-board procedures. Not all review boards are created equal. In Philadelphia, for example, review board members were pressured to judge allegations according to the norms of canon law. In one case, a canon lawyer who attended board meetings claimed that because an alleged act of abuse was committed against a 17-year-old in 1995, the allegation should be thrown out. At the time of the alleged abuse, the canonist argued, canon law held that the age of majority was sixteen. But review boards were not established to serve a canon-law function. Their role is simply to determine whether there is good reason to believe an alleged act of abuse took place against a minor.

What if the National Review Board published a handbook for diocesan boards? What's more, review-board members aren't always clear on what amounts to sexual abuse. Does plying a minor with alcohol count? What about inappropriate tickling? The Charter sets the standard as "an offense by a cleric against the Sixth Commandment of the Decalogue with a minor"—the one about adultery. That definition is vague enough to allow review boards to recommend actions against priests for a range of abusive acts, but it's also too idiosyncratic to be of much use to review boards. They need more guidance.

Third, require that all allegations be forwarded immediately to review boards. In many dioceses, such as Brooklyn, every allegation goes to the review board. In Philadelphia, however, someone with the archdiocese had been pre-screening accusations, deciding which were worthy of the review board's consideration and which were not. And in the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, the archdiocese never bothered to inform the review board that it had received the letter warning about Fr. Ratigan. When a bishop or one of his employees or priests is deciding which allegations ought to go to the review board and which he doesn't need to share, then he is undermining the purpose of the board. The USCCB should petition the Vatican to enact such a requirement in canon law.

But Will They Take Action?

These recommendations are hardly the stuff of special revelation. And yet it seems highly unlikely that when the bishops meet this week they'll make any significant revisions to their procedures. As reported by Religion News Service, a draft proposal barely alters the Charter. According to Bishop Blase Cupich of Spokane, chair of the U.S. Bishops' Committee on the Protection of Children and Young Adults, "the Charter is working." In one sense, Cupich is right. Abuse allegations are down. But in another sense, the Charter is not working, because the decisions of some bishops continue to put children at risk—by keeping cases of accused priests from lay scrutiny.

Many bishops were blindsided when they heard what had happened in Philadelphia. But should they have been? Bishops know that they have absolute autonomy in their dioceses. The USCCB has no authority to tell individual bishops how to run their shops. That's why there are still two bishops who refuse to participate in the annual audits that compile sexual-abuse allegations in U.S. dioceses. And there's nothing the USCCB can do about it—apart from suggest they mend their ways.

Could the Vatican intervene? Certainly. But when it comes to disciplining bishops, Rome tends to move slowly. It is loath to seem cavalier about usurping a bishop's authority in his own diocese; although there have been notable exceptions involving bishops with a liberal streak, such as Bishop Jacques Gaillot of Évreux, France, and Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen of Seattle.

And did Pope Benedict XVI have to promote one of the two holdout bishops—Robert Vasa—to a larger diocese? Did he not realize the message that sends to U.S. Catholics, who are still struggling to understand why Cardinal Bernard Law remains on the Congregation for Bishops in Rome, helping to decide episcopal appointments worldwide? Cardinal Rigali also sits on that influential Vatican congregation. If rumors are true, Rigali will soon be replaced and sent to Rome. (He's 76, one year past the mandatory retirement age.) A credible successor will be key to restoring the trust of Philadelphia Catholics. That appointment will also hold lessons for the wider church, including bishops. The question that remains, then, is what will they learn?

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.