By Mark Morris And Glenn E. Rice

Kansas City Star

June 18, 2011

http://www.kansascity.com/2011/06/17/2958462/before-furor-ratigan-raised-few.html

|

Shawn Francis Ratigan saw his future with the Catholic Church in 1979 as he stood with about 340,000 other believers in an Iowa farm field.

Pope John Paul II was making his first American visit, and Ratigan, a 13-year-old Boy Scout and the son of working-class parents from Grain Valley, traveled with a youth group on Oct. 4 to the Living History Farms just outside of Des Moines to see the pontiff.

Years later, when he spoke about the experience with a reporter from the Catholic Key, the local diocesan newspaper, Ratigan rhapsodized about the image of a charismatic leader shepherding the faithful.

“To see him out in that field was incredible,” Ratigan said before his own ordination in 2004. “There were hundreds of thousands of people. You saw the universal church.”

With the seed planted, Ratigan waited a few years before discussing the priesthood with the diocese’s vocations director, the Rev. Robert Murphy, a man who would play a critical role in Ratigan’s arrest almost 30 years later.

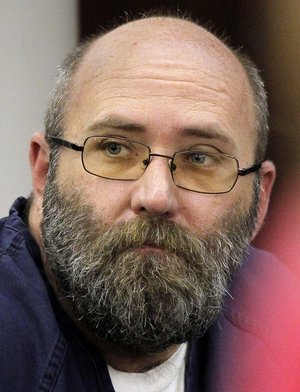

Today, Ratigan, 45, sits in a Clay County jail cell, awaiting trial on state child pornography charges for allegedly taking lewd photographs of girls.

Ratigan has pleaded not guilty. A lawyer representing Ratigan declined to comment Friday.

But the furor surrounding his arrest has spread far beyond Ratigan. The scandal has again wounded the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, which just three years ago agreed to pay $10 million to settle lawsuits filed by more than 40 victims of clergy sexual abuse.

Many of the faithful now question how vigorously Bishop Robert Finn and his top lieutenant, now Vicar General Robert Murphy, responded to concerns about Ratigan’s conduct that were raised last year.

Count Molly Cahill among the troubled. In 2004, she and her family were members of St. Thomas More parish, where Ratigan received his first post after ordination.

“It makes me sadder than I can tell you,” Cahill said recently. “My husband and I are, what we consider to be, extremely devoted to our faith. It’s not making me stronger right now.”

A Kansas City Star review of hundreds of pages of court records, public documents and published reports of his career reveals Ratigan to have been an energetic cleric who was taken with church orthodoxy.

Until a school principal sent a letter to diocesan authorities last year, raising questions about Ratigan’s conduct around children, no obvious red flags existed in his background. With a clean criminal record, Shawn Francis Ratigan appeared to be an exciting, motorcycle-loving priest with a heart for missions and service.

•••

Born in October 1965, Ratigan was the second of five children in the household of Francis and Karen Ratigan. Moving the family from Nebraska to Missouri in the early 1970s, the Ratigans started Midwest Church Furnishings, a business that renovated churches and sold them pews and refurbished furniture.

Karen Ratigan also worked at General Motors and took primary responsibility for caring for the family while her husband was on the road.

But if Shawn Ratigan seemed headed for the priesthood after graduating in 1984 from Savior of the World High School seminary in Kansas City, Kan., he quickly opted for something very different: helping his father in a bitter three-year divorce battle.

According to Jackson County court records, the separation came quickly in late December 1984, with Karen Ratigan complaining about her husband’s inattentiveness.

“Many times when traveling, he would stay and visit with friends and relatives for a few days rather than come home and take care of his responsibilities,” Karen Ratigan wrote in a court filing.

Francis Ratigan, in turn, pleaded with judges to maintain the status quo as a legal separation. Suffering from a chronic respiratory problem and “major depression,” he depended on his wife’s health insurance, which a divorce would cut off.

Through this period, according to court records, Shawn Ratigan stayed with his father and even accepted the divorce papers being served on his dad. He also lent money to his father, and eventually rejoined him on the road, renovating churches after the divorce became final in 1988.

Recalling that period with the Catholic Key reporter, Ratigan said renovating churches with his father, who died in 2001, had a profound effect on him. The buildings still were working churches, with Mass celebrated daily. And the Eucharist always was present.

“It was an unusual opportunity,” Ratigan said. “Most people don’t get to spend 10 hours a day in front of the Blessed Sacrament. It changed me.”

•••

Records from Conception Seminary College in Conception, Mo., show that Ratigan entered the school as a freshman undergraduate in 1996, 12 years after he graduated from high school. And though he said later that he’d worried about whether he could do the work, he graduated on schedule in 2000. Ratigan later joined Conception’s Board of Regents with about 30 others, including Finn.

Ratigan followed his work at Conception with four years of graduate theological studies at Mundelein Seminary near Chicago.

After his ordination in Kansas City on June 4, 2004, Ratigan joined St. Thomas More parish in Kansas City as associate pastor. Cahill remembered him as always being present for church events.

“He was very outgoing,” she said. “It was a time when the parish needed that sense of involvement.”

Only in retrospect, she said, did she realize that he carried a camera to every event.

And while at St. Thomas More, Ratigan met and became friends with Michele Kerwin and her family.

He taught her daughter knock-knock jokes and would engage Kerwin in long, good-natured theological debates.

“Shawn was conservative,” Kerwin recalled. “He would say, ‘There was a wrong way and the church’s way.’ I would say to him, ‘The church was not always right.’

“He would say, ‘Michele, you just have to trust the church.’?”

Kerwin also would tease Ratigan about his motorcycle, a 1994 Harley Davidson that an airbrush artist decorated, at some point, with themes that celebrated life. The gas tank bore the image of an angel bringing a baby down from heaven, while another spot carried a cross emblazoned with a ribbon reading, “Pro-Bikers for Life.”

With his transfer to the St. Joseph area in the summer of 2005, Ratigan’s public profile rose. Reporters there included him in articles discussing the significance of wearing crosses or noting his work as the chaplain of Bishop LeBlond High School.

And his travel on behalf of the church, and his commitment to its causes, drew notice. In January 2007, Finn joined Ratigan and 40 students from LeBlond for the long bus ride to Washington, D.C., for the annual March for Life rally, according to school records.

His zeal for the anti-abortion issue sometimes confused those around him. Three years after attending the Washington rally with Finn, he appeared before a group of fifth- and sixth-graders at a Northland parish school, asking them if they were “pro-life,” according to a memo the principal sent to the diocese in May 2010.

“Teachers said the kids were confused and weren’t sure how to answer,” Principal Julie Hess wrote. “Clearly, Father is unaware that most of the kids at that age don’t understand how babies are made, probably don’t know what abortion is, and may not understand the deeper meaning of being ‘pro-life.’?”

While in St. Joseph, Ratigan also organized summer mission trips to Guatemala for students and their families.

According to accounts in school newsletters, the students helped spruce up school classrooms, built wood-burning stoves and ovens and brought donations from the United States.

A photo from one trip published in a 2008 church newsletter shows Ratigan playing “Duck-Duck-Goose” with Guatemalan school children.

The Rev. Jerry Waris said Ratigan joined him and other members of a delegation that visited El Salvador in January 2010.

Waris said he wanted Ratigan, who had just taken over as pastor of St. Patrick Catholic Church in the Northland, to continue the church’s mission work there. Ratigan seemed to embrace the experience, Waris remembered.

“He got to meet the people of that community and seemed to enjoy the trip,” Waris said.

With his previous experience in Central America, Ratigan committed himself to maintaining the church’s relationships with impoverished parishes there, Waris said.

“That week was probably the most time I spent with him,” Waris said. “There was nothing that took place that would have alarmed me.”

•••

Shawn Ratigan — who won $1,000 with a Missouri Lottery Scratchers ticket in July 2008 — was a gambler.

In December 2010, whether he realized it or not, Ratigan placed one of the lowest percentage bets of his life when he handed his laptop computer to a repair person. Would the technician notice the allegedly lewd photos of girls under the age of 12? And if so, would he mention the photos to anyone?

Think of computer service technicians as the first-responders of child pornography investigations. They regularly have contributed valuable information to area child porn investigators for years.

Church officials seized Ratigan’s computer.

The next day, Ratigan, the son of a man who suffered from profound depression, retreated to his garage, fired up the pro-life Harley and waited for death.

According to court records, the church authorities and emergency medical workers who rescued him after he failed to appear for Mass that morning found a suicide note, in which Ratigan apologized for harm he had caused the church, the children and his family.

The man who counseled the troubled priest on clerical life after his epiphany in the Iowa cornfield, Monsignor Robert Murphy, already was involved in Ratigan’s problems.

After reading a memo from Hess the previous May, warning church leaders about Ratigan’s inappropriate behavior around children, Murphy counseled him on changing his conduct, according to a diocesan report.

A diocesan spokeswoman said this week that Murphy was out of town and unavailable for comment.

Three months after the December suicide attempt, Finn confronted Ratigan after hearing that he had attended a St. Patrick’s Day parade and a child’s birthday party.

After more defiance from Ratigan, Murphy in May contacted police and filed a police report, which unleashed a torrent of harsh questions and recriminations. A church-sponsored investigation headed by former U.S. Attorney Todd Graves could provide some answers in as little as 30 days on how the church managed Ratigan and the questions that surrounded him.

But rebuilding trust in a family of faith is painful, said Kerwin, the St. Thomas More parishioner.

“All of this is incredibly hard to understand,” she said. “It really hurts the trust. And we don’t need any more of that.

“We need to have trust.”

The Star’s Judy L. Thomas contributed to this report. To contact Glenn E. Rice, call 816-234-4341 or send email to grice@kcstar.com

To contact Mark Morris, call 816-234-4310 or send email to mmorris@kcstar.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.