By Austen Ivereigh

America Magazine

June 22, 2011

http://www.americamagazine.org/blog/entry.cfm?blog_id=2&entry_id=4332

|

A documentary shown last night on the BBC told a familiar story of clerical sex abuse. Four members of the Rosminian order regularly abused boys in their care at two schools -- one in the UK, the other in Africa -- in the 1950s. 'Abused - breaking the silence' was an extremely well-made, sensitive film, which explored the question of reparation: is forgiveness, especially when it is sought by the abuser, a substitute for justice?

The program brings us into the appalling, lonely, shameful world of the sexually abused child in the grip of a power that is as absolute as it is ruthless. The shock is heightened because those remembering the events are educated, intelligent, professional middle-class men, now in their fifties, who met up again a few years ago in internet chat rooms, recalling their school days. One by one they discovered that what they thought had been their own private hell had been shared by others. That realisation led to them deciding to compiling a record of their experiences and confronting their accusers.

On film they often break down as they describe how they are forced to masturbate priests, are fondled and grasped while in bed or during punishments, and told to keep silent. They showed how the sexual abuse went along with a casual physical brutality. "You could be beaten by a priest who would hours later be fondling your penis", one of them recalls. Complaints would occasionally register, but the most that would happen to a priest would be a transfer to another school and more victims.

A lot of the advance coverage of the program, however, has been about something else entirely: the shock of discovering that a priest whom you trusted, liked and admired has turned out to be an abuser of children decades before.

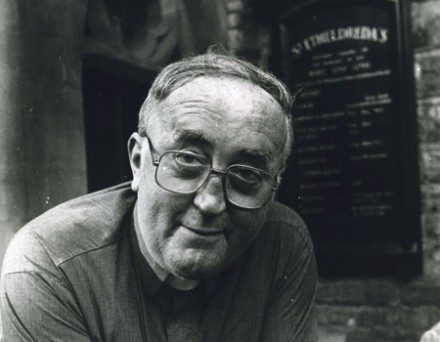

The matter has received unusal attention because one of the four abusive priests in the program, Fr Christopher ("Kit") Cunningham [pictured], was until his death in December last year the popular and highly regarded rector of an old and beautiful City of London church, St Etheldreda's, which was popular with people looking for traditional liturgy. Because of the church's proximity to Fleet St, traditional home of the print media, Fr Kit was the unofficial chaplain to Catholic journalists, and the actual chaplain of a conservative guild of Catholic writers called The Keys. He was a dearly loved friend and pastor to some of Britain's best-known Catholic scribes.

They are now grappling with a deep sense of anger and betrayal. The article in last Sunday's Observer by Peter Stanford, once the editor of the Catholic Herald, now a Tablet columnist and the author of many books, is well worth reading. Fr Kit married him, and Peter named his son after the priest. When Fr Kit died Peter, knowing nothing of his past, wrote a glowing tribute in the Guardian which caused one of the priest's victims to contact him. Thus did Peter learn, earlier than the rest of us, what the priest had done.

Or consider Mary Kenny, longtime Catholic Herald columnist, writing in the Irish Independent of Fr Kit's many qualities -- his kindness, his outreach to the poor, his ecumenical friendships -- which she is now trying to reconcile with the man she has discovered abused six boys as young as eight. "We wonder why clerical abuse was "covered up", as well as how it could have occurred," she writes. "Now I know the answer. Because, at first, you just cannot believe it. It seems so utterly uncharacteristic of the guy you knew."

What is fuelling the anger of many are the actions and inactions of the Provincial of the Rosminians in England, Fr David Myers. The program records how, when the victims first contacted him in 2009 with a dossier of abuse they had compiled, he was deeply shocked and took the accusations to those they had accused (by now old men). What followed were letters to the victims asking for forgiveness and meetings arranged between the priests and some of the victims in London. One man, Don, went to see Fr Kit at his care home shortly before his death. Fr Kit, by now in a wheelchair, had two broken fingers and looked frail; after the meeting, says Don, he felt his feelings of anger and bitterness lift for the first time.

Overall, however, these attempts at reconciliation failed (one of the priests, Fr Collins, is secretly filmed denying to one of the victims abuse he has earlier admitted to in a letter). Now, 22 of the 35 victims are suing for compensation. Fr Myers tried to dissuade them, questioning their moral right to financial compensation on the grounds that it would take money from the order's charitable work. Understandably, the victims reject this idea: money is the traditional way, in law, of acknowledging harm and seeking reparation.

But what so deeply offends the victims and many of writers now in shock is the way Fr Myers led Fr Kit's memorial service in January this year. No mention was made on that occasion of the accusations, nor of Fr Kit's confessions, nor of the way he had returned his MBE award to the Queen. One of the victims recorded Fr Myers's homily, which gives no hint of what by this time were fully acknowledged acts of abuse; such denial is a dpouble slap in the face for those seeking justice. Those who, like Francis Phillips in the Catholic Herald, wrote warm obituaries, feel doubly betrayed -- not just as a friend, but as a journalist.

In what looks like a spectacular lesson in how not to deal with such accusations, Fr Myers declines to take part in the program, refusing, in a letter to the BBC, to be "video-ed and edited", and quoting Lamentations 3:16: "It is good to wait in silence".

Not only is there no apology, contrition, or acknowledgement of the pain and damage caused by the order's failures, but Scripture is invoked to justify what looks inevitably like high-handed insensitivity, putting institutional reputation above justice and accountability. Although today Fr Myers appears to have received better counsel and put out a statement -- good, but why not say it yesterday, in advance of the broadcast? -- the Rosminians appear to have learned almost nothing from the lessons of the clerical sex abuse crisis. This is even sadder given that much of this drama took place last year at the time of the visit of Pope Benedict XVI, who set great store by justice, reparation, accountability and transparency in child protection.

Unsurprisingly, just one of the 35 victims of abuse in those two schools still goes to Mass.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.