Crossroads for Children

The Age

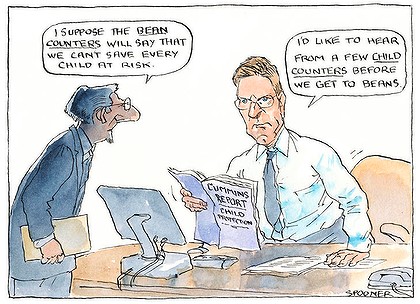

The Baillieu government should at the very least be congratulated for commissioning and promptly releasing the Cummins report on child protection. By any measure it is a landmark study, laying bare an issue that the previous Labor government shamefully squibbed. Depending on how this government ultimately responds, the report will be held up as a glowing achievement of the Coalition's first term or an emblem of yet more political inaction. As the report makes clear, our system has failed for years to protect Victoria's most vulnerable children. It is a mess, and, for an affluent and sophisticated society such as ours, a disgrace. The facts are compelling. During the past decade, the number of children in out-of-home care grew by 44 per cent, reaching 5700 by the middle of last year. In 2011 there were 55,000 reports made to the Department of Human Services by Victorians concerned about the welfare of individual children. Many of these children seem to be caught in a revolving door. Two-thirds of the cases reported to the department had already been the subject of alerts at least once before. More than 2000 were the subject of more than 10 reports. If the current rates continue, an almost unbelievable one in four children born last year will have been reported to the department at least once by their 18th birthday. This is not to say the reporting rates will, or can be allowed to, continue, but it is nevertheless an alarming thought. It might be argued that the sharp rise merely shows that the system is increasingly working as intended. It isn't. The huge jump in child protection reports during the past decade has not been matched by an increase in action by authorities to tackle abuse or neglect, which is often linked to alcohol and drug abuse, mental illness or other disadvantage. On the contrary, the number of investigations and ''substantiations'' confirming neglect or abuse has actually declined, while the number of court orders has risen at a far slower rate than the number of reports made to the department. Over the past decade, the number of deaths of children known to child protection workers has more than doubled, rising from 12 in 2001 to 29 in 2010, with a total of 295 deaths since 1996. Clearly, the system is failing to cope with the rising volume of reports. Part of the problem is that government agencies are not held accountable for the support they provide, given a government-wide obsession with ''outputs'' rather than the specific needs of individual children. There is little co-ordination between government departments and a woeful lack of focus on actual outcomes. As the report notes, about half of the state's 5700 children in out-of-home care have below or well-below-average levels of education by year 9, and by year 10 they experience ''very poor'' education outcomes. The Baillieu government's formal response to the 900-page report so far has consisted of a press release promising an extra $61 million over four years to ''immediately start improvements to service delivery at the front line''. The money will be used to fund an extra 42 child protection workers, expand family support services in areas of ''extreme demand'' and provide targeted services to help tackle child sexual abuse. But the extra $15 million a year represents a tiny step towards fixing what is an immense problem, particularly when you consider Victoria's child protection spending is already relatively modest compared with that of other states - about $400 per child compared with almost $600 for the nation overall. The report's 90 recommendations include broadening the professions covered by mandatory reporting requirements from teachers, police and medical professionals to include priests, childcare workers and kindergarten teachers. In one of its most controversial recommendations, the report urges the government to repeal laws allowing judges to suppress the names of convicted sex offenders, claiming ''parents and families have a right to know if a serious sex offender is residing among them''. Clearly there are structural and legal changes the government could make at little cost. But the report makes clear that finding more money will be a central issue. As Community Services Minister Mary Wooldridge conceded yesterday, it comes down to resources. ''We've had a long-standing position that the workforce has been under massive pressure, it's been a crisis … and we are working through that,'' she said. The problem is the government's broader political strategy relies on the idea of building a stockpile of budget surpluses to pay for future infrastructure without taking on more debt. ''Fixing the problems'' in child protection may be an important objective, but the government is also under pressure to boost spending on health, education and transport - all at a time when money is in short supply. The government's decision to slash 3600 positions from the public service is further confusing the message. It insists that the job cuts - representing about 10 per cent of the ''core'' public service - will not hurt ''frontline'' services. What this actually means in reality is less clear, given that frontline and ''back-office'' staff presumably work in tandem. How one can be cut without affecting the other remains a mystery. The question is, will there be a future clash between good intentions, sound advice and money in an environment where our political leaders are seeking to reduce the size of government? If there is a future trade-off - and there almost certainly will be - one can only hope common decency prevails. Victoria's vulnerable children deserve nothing less.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.