Will Lynch Trial Update: Prosecutor Tells Jurors She Expects Priest 'Will Lie to You'

By Tracey Kaplan and Robert Salonga

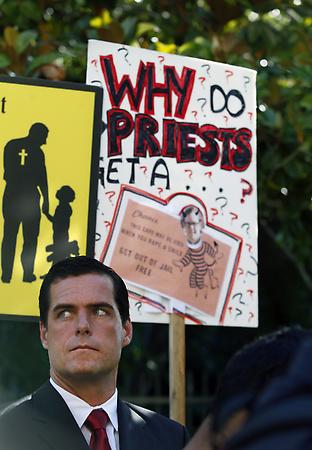

Evidence will show the man on trial in the beating of an aging Jesuit priest was abused by the priest, but that still did not give him the right to take the law into in his own hands, prosecutors in Northern California said today in their opening statement in the trial of William Lynch. Lynch, 44, is accused of beating the Rev. Jerold Lindner in 2010 in front of startled witnesses at a retirement home for priests. Lynch has said Lindner abused him and his brother during a camping trip in Northern California. For someone essentially described as a monster -- including by the prosecutor, who stated unequivocally that Lindner molested the Lynch brothers -- the priest looked like an ordinary 67-year-old rotund guy with white hair, a bushy moustache and thick glasses when he took the stand Wednesday afternoon. With every eye in the courtroom on him, and in complete silence, he walked slowly up to the stand in a loose chambray shirt and baggy khakis. Santa Clara County Deputy District Attorney Vicki Gemetti, who began her 20-minute opening displaying a blown-up photograph of a bruised and bloodied Lindner slumped in a chair, and emploring jurors to focus solely on the assault, which she said Lynch "undeniably" committed. At the time of the attack Lindner was 65. Speaking in court, the priest told jurors he'd been removed from active ministry in 1997 after the Lynch brothers accused him of molesting them, and assigned to the center permanently in 2002. He said he didn't recognize the visitor who came to the Los Gatos center on May 10, 2010. In court, he identified that man as Lynch. The priest said he entered the room that day expecting to be told of a death in his family. Lindner testified that the man told him to close the doors and then asked if the priest recognized him. Lindner said he didn't. "He got up and walked towards me and said "do you recognize me," again. I was pretty puzzled," he said. Lindner said that the man told him to take off his glasses and immediately began landing "stinging" blows on his face, arm and head, and kicked him once in the inner thigh. The first punch was "a vicious blow, major impact," he testified. "I was stunned. I had no idea what was happening." Lindner said Lynch accused him of molesting him and his brother only after he started punching him. In contrast, Lynch's defense attorney Pat Harris elicited testimony from Santos, a retired receptionist who worked at the Sacred Heart center for 17 years, that suggested the two men could have been in the room talking for five minutes before Lindner cried out for help. Gemetti wound up the day asking the question many in the courtroom who knew the priest from decades ago and came to mistrust him were waiting for. "Did you molest the defendant?" No, the priest said. "Did you molest his brother?" Again, the answer came quickly: No. With the day drawing to a close, the judge dismissed the jury; Harris will get to cross-examine Lindner tomorrow. Without the jury Outside the presence of the jurors, Harris asked the judge to start Thursday's session with a bombshell, albeit one that wouldn't be entirely unexpected. "He has chosen to perjure himself," Harris said. "He should be advised of his right to counsel." Gemetti told the judge Lindner already has a lawyer who came to court with him. Nonetheless, Harris repeated his request, saying the judge should make what would be a damning statement on the record for jurors to hear. Judge David Cena said he'd think about it. Santos was Gemetti's first witness and was staffing the front desk when Lynch called using a pseudonym to see if Lindner was there and later arrived at the center, ostensibly to give Lindner notification of a death in the priest's family. Santos, who has white hair and now relies on a cane, admitted she remembers that day only "vaguely" and can't recall exactly what she heard or saw when she opened the door of the guest parlor where Lynch and Lindner met, or how long they met. However, she said she did hear the priest calling, "help, help me" several times. She also did not make a positive identification of Lynch in court, saying she saw a shadowy figure because the light was behind him when he entered through the center's front door. But she put the audience in the center with her that day when she said, "I was frightened and I just wanted to call he police. I was afraid he was going to kill Father Lindner -- Father Lindner was not a huge man -- that he would choke him, the way he held him down. I wasn't sure what he would do." In her opening statements earlier in the day, Gemetti pointing to the blown-up photograph, Gemetti said the first question that comes to mind is, "Who beat up this old man?" Pausing for dramatic effect, she answered her own question: "The defendant beat up this old man." On the theory that the best defense is a good offense, Gemetti quickly acknowledged, "The evidence will show (Lindner) molested the defendant all those years ago." She went even further in an attempt to defuse the potential impact of the defense's strategy, saying she expected her lead witness -- Lindner -- to be untruthful when he takes the stand, perhaps later today. "I expect he will lie to you," she said, "or say he doesn't remember." The concession was striking -- one attorney at the hearing said he never heard a prosecutor say that before in 30 years of practicing criminal law. It gave defense attorney Harris ammunition to use in his opening. "The evidence is going to show that only two men know what happened in the room that day," he said. "One of them, the prosecutor already told you, is probably going to lie. Another has lived this story his entire life and he is going to tell you what happened." Harris displayed photos of the two brothers from around the time of the camping trip during his opening statement. "This case did not begin in 2010," Harris said. "It began on a holiday weekend in the mid-1970s." Showed up Harris denied that Lynch intended to assault the priest when he showed up at the retirement home. Harris didn't go into details during his own 20-minute opening statement, but promised the jury Lynch would testify and explain his actions. Harris also said he expected the priest to lie when he is called to testify. Harris told the jurors to take the priest's credibility into account when deciding the case. Harris also tried to minimize the gravity of the attack, saying the priest did not think his cuts and bruises warranted a hospital visit until he was urged to go by a paramedic. Gemetti promised the jury that they would hear from at least two employees of the Jesuit center who saw or heard the violent attack. One of Gemetti's witnesses is likely to be Mary Eden, who she said was the head of nursing at the Jesuit center. Eden testified during the preliminary hearing last year that Lindner was on a list of molesters the Jesuits keep. However, she also testified that she saw Lynch strike Lindner. Harris in his opening statement already tried to make much of the bucolic lifestyle Lindner enjoys at Sacred Heart with "no restrictions" despite his history of molestation allegations. "I'd like to retire there," Harris said of the center. Moving slowly The prosecution took the offense by calling Lindner to the stand. This way, jurors' first impression of him would be as a victim. Regarding his truthfulness, the jury was advised that they can believe "all or a part" of witnesses' testimony, meaning they could buy his account of the alleged beating, and disregard his statements about the alleged rape of Lynch and his brother. Lynch is charged with two felonies that together carry a maximum sentence of four years -- assault by means of force likely to produce great bodily injury and also elder abuse under circumstances likely to produce great bodily harm or death. Relatives and other people supporting Lynch showed up early at the Hall of Justice in San Jose, including Lynch's mother, Peggy. When Lynch arrived, he was surrounded by a throng of supporters, a number of them carrying signs. One of the signs read: "Stop Clergy sex abuse." Lynch supporters also rallied outside the courthouse after the hearing broke for lunch, holding picket signs and chanting "Jail Father Jerry." Among them was Tamara Roehm, 44, who is Lindner's niece and said she was one of his child victims. She hasn't seen Lindner since she was a teenager and hoped to get a glimpse of him, but said she was turned away from the courtroom because she is a scheduled witness. Roehm showed up for the trial's first day to back Lynch's effort to shed light on her uncle's crimes. "Somebody from the Lindner family should be supporting him," Roehm said, referring to Lynch. She added that she hopes the trial spurs efforts to remove the statute of limitations that precluded Lindner from being tried for his acts against her and Lynch's families. "This is bigger than one family. It's for kids everywhere," she said. The primary reason she'd like to see changes is because child victims are often too timid to speak up, especially against someone like Lindner, revered at the time by both her family and religious circles. That aura of infallibility, Roehm said, intimidates children from thinking they'll be believed. "He, and all pedophiles know that," she said. The priest has denied that he molested then 7-year-old Lynch and his 4-year-old brother 35 years ago on a camping trip sponsored by a religious group. Paul Smith, who started the camping trips, was one of those who showed up to support Lynch Wednesday. "Unfortunately, we invited Father Jerry," Smith said. The Jesuits have doled out millions of dollars to settle cases brought by Lindner's victims, including the Lynch brothers. But the priest was never prosecuted because Lynch and others reported the abuse after the brief window of opportunity set by the statute of limitations at the time slammed shut. "There shouldn't be a statute of limitations on this. It's ridiculous," said Bryan Delaney, who attended the camp with Lynch. Determined to "out" Lindner, Lynch chose to let the case go to trial rather than negotiate a plea deal for no more than a year in jail. Lindner is being brought in and out of court under the protection of armed bailiffs because of a protest against him in front of the courthouse. Harris will have an opportunity to cross-examine the priest. Competition for seats in the packed courtroom was intense. More than 70 people stood in line for nearly 90 minutes to get in, including about 15 prosecutors who came to support Gemetti. The group included families who had gone on camping trips with the Lynches, as well as one of Lynch's Kappa Sigma frat brothers. It was so crowded that bailiffs had to turn away a handful of Lynch's disappointed supporters. The jury is composed of nine men and three women. Prosecutors generally regard female jurors as more skeptical and less willing to find defendants accused of sex crimes guilty. But in this case, they may have felt women would be too sympathetic toward Lynch, an alleged child victim. In contrast, it is likely the defense would welcome male jurors, particularly blue-collar workers, who may identify with Lynch's anger.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.