The Redemption of Sinead O'connor

By Michael Agresta

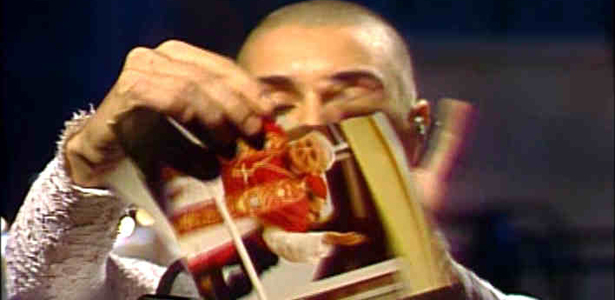

In the weeks and months after Sinead O'Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II on live television, commentators in the media sought to explain the motives of her protest. Very few, however, made use of the traditional tools of journalism: interviews, research, and textual analysis. Instead, most commentators seem to have consulted their own imaginations. On the right, John Cardinal O'Connor in Catholic New York suggested that the singer had employed "voodoo" or "sympathetic magic" to physically destroy her enemy in the Vatican—an extraordinarily poor choice of imagery for a Church authority attempting to silence an outspoken female. On the left, Richard Roeper in the Chicago Sun-Times celebrated Sinead for providing "a moment of truly great television." He assumed offhand that she was protesting the Vatican's positions on women's rights or the ongoing violence in Northern Ireland, but he focused his praise on O'Connor's acumen as an entertainer. Anthony DeCurtis, writing Rolling Stone's December "Year in Music" feature, perhaps best summed up the American entertainment media's reading of the protest: Sinead O'Connor, meanwhile, managed the seemingly insurmountable task of pushing the bondage-clad Madonna out of the headlines with her bizarre attacks on what she quaintly and archaically refers to as the Holy Roman Empire. The Catholic church is a perfectly legitimate target, particularly for an Irish single mother who grew up in an impoverished country in which Catholicism is virtually a state religion, contraception is discouraged and abortion is banned. But is O'Connor's aim to educate people about her point of view or to alienate them and insult their beliefs—as she did when she ripped up a picture of the pope on Saturday Night Live, ensuring that they will never take her seriously? DeCurtis and Roeper provided their own speculative reasons for O'Connor's protest plucked from American headlines at the time, like access to contraception, abortion, and the Troubles. Almost entirely overlooked in the controversy was the text of O'Connor's protest—a Bob Marley song, "War," with lyrics taken from a speech by Haile Selassie. O'Connor had replaced out-of-date lyrics about apartheid African regimes with the phrase "child abuse, yeah," repeated twice with spine-stiffening venom. Also inexplicably ignored were O'Connor's own words, in an interview published in Time a month after her SNL appearance: It's not the man, obviously—it's the office and the symbol of the organization that he represents... In Ireland we see our people are manifesting the highest incidence in Europe of child abuse. This is a direct result of the fact that they're not in contact with their history as Irish people and the fact that in the schools, the priests have been beating the shit out of the children for years and sexually abusing them. This is the example that's been set for the people of Ireland. They have been controlled by the church, the very people who authorized what was done to them, who gave permission for what was done to them. Her interviewer seemed confused by the connection O'Connor was making between the Catholic Church and child abuse, so O'Connor opened up about her own history of abuse: Sexual and physical. Psychological. Spiritual. Emotional. Verbal. I went to school every day covered in bruises, boils, sties and face welts, you name it. Nobody ever said a bloody word or did a thing. Naturally I was very angered by the whole thing, and I had to find out why it happened... The thing that helped me most was the 12-step group, the Adult Children of Alcoholics/Dysfunctional Families. My mother was a Valium addict. What happened to me is a direct result of what happened to my mother and what happened to her in her house and in school. The interviewer remained skeptical of O'Connor's characterization of Irish schools as playgrounds and training grounds for child abusers, and the interview moved on to different topics. * * * By now, the history of sexual and physical abuse in the Irish Catholic school system is familiar. As late as 2007, the Church controlled 93% of the schools in Ireland, giving most children no hope of escaping the often-sadistic system. As in America, serial child molesters like Brendan Smyth were shuttled from parish to parish and school to school to keep a step ahead of police and complaining parents. The culture of permissiveness towards abuse affected all communities, but probably the worst off were poor, orphaned, and troublemaking children sent to residential reformatory and industrial schools. To read the 2009 Ryan Report covering crimes carried out against children in these settings is to court a special sort of nausea—the kind that comes from bearing witness to an organized effort to deny the dignity of individual life and make the bodies of the powerless available to service the needs of the powerful. In this case, the powerless were disadvantaged minor teenagers and children. Sexual abuse in several industrial schools was described as a "chronic problem." Clergy whose behavior drew complaints from parents of day-school students were transferred to industrial schools where their abuses drew less attention. Some schools seem, on the evidence, to have been more labor camps than institutions of learning. At one notorious industrial school in Dublin, each child was required to string 60 rosaries each weekday and 90 on Saturdays. Students who did not reach their quotas were beaten. "The sheer scale and longevity of the torment inflected on defenceless children—over 800 known abusers in over 200 Catholic institutions during a period of 35 years—should alone make it clear that it was not accidental or opportunistic but systematic," the Irish Times wrote upon reviewing the Ryan Report. "Abuse was not a failure of the system. It was the system." At age 15, Sinead O'Connor was caught shoplifting and was sent to an institution much like those investigated in the Commission Report, a Magdalene laundry full of teenage girls who had been judged too promiscuous or uncooperative for civil society. "We worked in the basement, washing priests' clothes in sinks with cold water and bars of soap," O'Connor has written of her experience. "We studied math and typing. We had limited contact with our families. We earned no wages. One of the nuns, at least, was kind to me and gave me my first guitar." On the grounds of one Dublin Magdalene laundry, a mass grave was uncovered which included 22 unidentified bodies. These institutions have since caught the eye of the United Nations Committee against Torture. After 18 months, with the help of her father, O'Connor escaped from this brutal system. Very quickly, her voice carried her to stardom. Her former captors were the "enemy" O'Connor spoke of when, as a 25-year-old with a once-in-a-lifetime live television audience, she tore the picture of the Pope and exhorted her viewers to "fight" him. The picture she tore, in fact, had belonged to her abusive mother, then already dead. "The photo itself had been on my mother's bedroom wall since the day the fucker was enthroned in 1978," she told the Irish magazine Hot Press in 2010. It was a symbol of O'Connor's own personal history of abuse and the unspoken culture of abuse that still held sway in her home country. In the weeks after her SNL appearance, she released a public letter urging her fellow Irish to pursue truth and reconciliation with the Church: The only hope for me as an abused child was to look back into my childhood and face some very difficult memories and some desperately painful feelings and a lot of very tricky conversations! I had to have it acknowledged what was done to me so that I could forgive and be free. So, it has occurred to me that the only hope of recovery for my people is to look back into our history. Face some very difficult truths and some very frightening feelings. It must be acknowledged what was done to us so we can forgive and be free. If the truth remains hidden then the brutality under which I grew up will continue for thousands of Irish children. These paragraphs were skimmed over by critics like DeCurtis, who could only make sense of passages about abortion and the Holy Roman Empire. "It's very understandable that the American people did not know what I was going on about," a more serene O'Connor reflected in 2002, in an interview with Salon. "But outside of America, people did really know and it was quite supported and I think very well understood." The crimes of pedophile priests and sadistic Irish schoolmasters did not begin to unravel in the public eye until several years after O'Connor's protest. The matter is still far from resolved, but at least the broad facts are now available for public consideration. O'Connor should not be considered the central figure in the uncovering of the abuses, but neither can one understate the impact of a major pop star's provocations on her country's eventual willingness to come to terms with its iniquities. * * * In America, however, the protest effectively ended O'Connor's career. Joe Pesci, hosting SNL the next week, told the crowd, "She's lucky it wasn't my show. Cause if it was my show, I would have gave her such a smack. I would have grabbed her by her... her eyebrows. I woulda..." (tossing gesture) He was met with laughter and applause. On October 16, at a tribute concert to Bob Dylan, O'Connor faced a hostile crowd. Defiantly, she asked her band for silence and briefly attempted to reprise her a capella performance of "War." She broke off and fled the stage in a hail of catcalls and boos. Dylan made no statement in her defense. Around the same time, at a rally in New York, piles of her records, tapes, and CDs were crushed by a steamroller. Protesters declared the United States a "Sinead O'Connor-free zone." Within a year of her SNL protest, O'Connor had disappeared from the American pop scene, quickly replaced by a new glottis-catching Irish pixie dream girl, Dolores O'Riordan of the Cranberries. Some of the damage to O'Connor's career, of course, was self-inflicted. On October 29, 1992, Rolling Stone published an embarrassing interview given by O'Connor before the SNL performance. In the interview, O'Connor called Mike Tyson's rape victim a "bitch," criticizing her public appearances on talk shows around the time of Tyson's conviction. She also proposed an adolescent vision of transformational social change, suggesting that if no one voted or went to work, the world's institutions would be somehow regenerated and improved. The interview perfectly captured a portrait of the singer as a young, politically naive firebrand, courting controversy for controversy's sake. It fit the preconceptions of both champions like Roeper and critics like DeCurtis, and her protest was dismissed before it was ever properly heard. But effective American political protest, from Rosa Parks to Cindy Sheehan, has often relied on imperfect messengers. Why then did O'Connor's protest in particular fall on deaf ears? Was it due to the foreignness of her complaint? American Catholics would, of course, within a decade of her SNL appearance, discover themselves in the midst of a priestly sexual abuse scandal of their own. O'Connor's alarm bell was meant for them as well. More likely, America was unable to hear out, let alone accept, O'Connor's protest because we were unwilling, in DeCurtis's words, to "take seriously" the provocations of an entertainer who would put her career on the line to make a point. We tend to look to our musicians as entertainment professionals—an expansive identity into which Dylan, for instance, has found a comfortable retreat in his late years. A musician with no self-preservation instinct is considered highly unprofessional. O'Connor came from a different culture and came to us as an unfamiliar type—a true believer. She often spoke of her voice as a gift from God to lift her out of the "hell" of her childhood and compared herself to her role model, Joan of Arc. In 2002 she told Salon: I felt that I was having a relationship with what I would call the Holy Spirit. My feeling all my life was that thing did come and help me through some very difficult times and my intention was always to help it, then. And when I got older I got the chance. The thing is, if that spirit asked me to do something, then I had a lot more to fear by not doing that thing than I had by doing it and dealing with the consequences of what people think. O'Connor actually seems to believe that she was specially endowed by God with a powerful voice in order to restore integrity to a corrupted Church and put an end to the pervasive evil of child abuse. This belief is born out not only in her interviews but also in her music. In a secular, psychology-oriented society, this might be seen as a manic delusion—indeed, O'Connor was recently diagnosed as bipolar. But in a highly religious society like the one that forged her, this sort of faith-based crusade is not only valid but represents one of the few available models of effective reform, followed by King and Gandhi, among others. To claim to speak for God is to appeal both to the individual's spiritual integrity and to a moral authority higher than that of the earthly powers that be. This appeal was at the heart of O'Connor's SNL protest, as she prophesied a future of damning reports of abuse and dwindling Catholic flocks. If we in the American entertainment media couldn't see O'Connor for the prophet she was, we were off the mark in blaming the messenger. We could have done a much better job of listening to what she had to say.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.