Ireland's Magdalene Laundries: I Hope My Birth Mother Can Now Rest in Peace

By Samantha Long

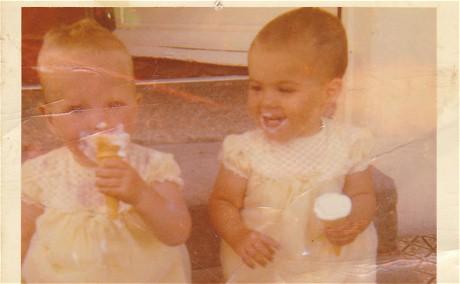

Later today the Irish prime Minister, Enda Kenny, is expected to offer a full apology for the suffering endured by thousands of women locked up in the Magdalene Laundries. Here, Samantha Long, the daughter of Margaret Bullen, who died in one of the laundries, shares her birth mother’s tragic story. In 1993, at the age of twenty one my twin sister Etta felt a need and a curiosity to trace our beginnings. We had been adopted together at the age of nine months and always knew that – our loving upbringing was secure and carefree. After a two year search, our social worker telephoned to say that she had located our biological mother and she was ready to meet. We expected to find a married woman with other children, who had moved on with her life and her past. Nothing prepared us for what we found. Margaret Bullen had been committed to Ireland’s Industrial School system at the age of two years because her mother was unwell and her father was unable to take care of their seven children. That was the end of Margaret and the outside world. By the age of five she was preparing breakfast for 70 children including herself. This work started at 4am after kneeling in the cold to say the rosary first. A fellow female child slave from this institution has told me that Margaret was a fretful bed-wetter, and to this day that woman can still imagine the smell of urine as the girls knelt to pray before dawn. Moving to the Gloucester Street Magdalene Laundry Margaret continued her childhood and puberty in these institutions, without the chance to grow up. At age 16, she was transferred to the Gloucester Street Magdalene Laundry just off O’Connell Street in our capital city. There she toiled, unpaid for the rest of her life. The working conditions were hard, with long hours of tortuous labour carried out in the strictest silence. Meals were meagre, and recreation time consisted of other types of unpaid work, such as embroidery or basket-making. When we were reunited, Margaret was 42, but looked like a woman 20 years older. Margaret didn’t tell us all the details of her life. She was too ashamed and seemed to think that we might look down on her or her work. That was understandable, because the rest of society was conditioned to feel superior to these “fallen women”. Margaret was committed to the care of the Irish state, and the state sub-contracted that duty of care to the Catholic Church. The state forgot all about the women once they went in. They should have checked on their physical, educational, nutritional, psychological, recreational well-being. But they didn’t – instead the state gave many laundry contracts to the religious sisters, and that slave labour was carried out by women like Margaret, who spent most of her life washing the bed linen and clothing from Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. She did not remember giving birth three times Despite being in the care of the church and state, Margaret became pregnant twice although she did not live in the free world. At age 19 she gave birth to my twin sister Etta and I, followed three years later by another daughter, whom we have never met. Upon being informed that her daughters had traced her and were ready to meet, Margaret had an emotional breakdown because she did not recall that she had given birth, presumably due to the post traumatic stress of having us taken away from her without consent or warning seven weeks after we were born. But all of the documentation was verified, not to mention our strong resemblance to her. We enjoyed a few years of knowing Margaret, although because of the lapse of time and her severe institutionalisation, it was a bumpy road for all of us. I felt very loyal to my adoptive mum, Anne, and to my dad, and found the initial process of meeting quite difficult. However, our family were fully embracing of Margaret and we never regret our tracing or relationship. We are proud of our legacy. Margaret died whilst still on the inside. She was one day shy of her 51st birthday. The laundry ceased to operate in 1996, but the women continued to live there in the same conditions as before. Some people have asked why we didn't take her out but she was so deeply institutionalised that we would not have had the necessary understanding or qualifications to deal with her possible re-integration into society. Also, we were just starting our own adult lives, careers and relationships and it would have been too difficult for everyone, including Margaret. Her death certificate records her cause of death as Goodpasture Syndrome, a disease caused by inhalation of chemicals over many years resulting in end stage kidney and liver failure. She is buried in a communal grave in Glasnevin cemetery, in the shadows of Michael Collins and Daniel O’Connell – the great liberator. Every moment of Margaret's life was not bad, and she did have her own pals and community in there, and indeed one or two kind nuns; but overall this should not have been the fate of a vulnerable girl in modern Ireland. Hopeful of a state apology today The McAleese Report, which was published earlier this month, vindicated the position of myself and others who gave testimony to the one thousand page report. It confirmed that there was state involvement in the running of the Magdalene Laundries. Unfortunately it did not find evidence of physical abuse, which many have found surprising, considering what they went through. They bear physical and emotional scars. Whether a woman was in a laundry for one month or 34 years like Margaret, they all have one thing in common. They were branded for life. I am hopeful of a state apology when the report is debated by the Irish Parliament this evening and I am confident that it will come. For the less than one thousand women who are still alive, I wish that they get the monetary compensation they deserve in the winter of their lives. There is also a vigil planned outside the Dáil from 4pm in support of the women which has been organised by The National Womens' Council of Ireland. I won't be present for the apology if, and when it hopefully comes. I will be tuning in live at home with my husband and children - exactly the place I want to be at that moment. For Margaret, an apology is all that she can get from beyond the grave. I would welcome that and I am convinced that she would be aware of her vindication and moral victory. Rest in peace.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.