As Non-catholic Kids, We Did Wonder about Priests. but We Were Way off

By Ian Jack

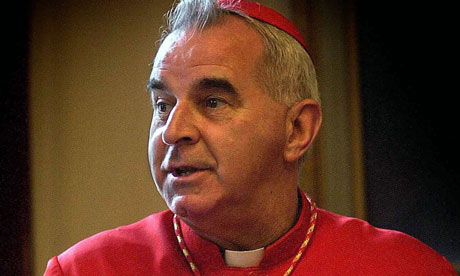

When we were boys and girls, did we have any idea what priests got up to? Perhaps some Catholic children did, when they came across those now identified as bad apples, but for the rest of us they remained rarely seen, black-clad figures who (we were told) exercised a severe power over their congregations. Old films showed them as shrewd and humorous characters played by the likes of Bing Crosby and Spencer Tracy, and though as Protestant or at least non-Catholic children we never swallowed that sunny version, they appeared sinister to us only in the most general way. I remember a moment of teenage speculation when, looking at the drawn curtains of a priest's house one winter's night, one of us wondered about the female housekeeper's role. A dozen years later, post-midnight in the lounge of a grand Dublin hotel, I saw a group of bibulous priests getting pie-eyed in what one of Cardinal Keith O'Brien's accusers would call a "late-night drinking session". To anyone raised with the purse-lipped notion that men of God should always be sober, this was a memorable scene, and for quite a few years after, maybe even until the advent of Father Ted, it represented my idea of "inappropriate behaviour" in the priesthood. That the same priests might end up undressing one another would then have been a preposterous suggestion. We knew so very little. The clerical uniform successfully erased the individual inside it, so that instead of seeing a 25-year-old man of amiable intention and uncertain sexuality – quiet Pat Flannery, say, from the next street – we saw a member of a secret society with a lineage that went all the way back to the Spanish Inquisition. But then, we were on the outside. As a family of non-believers, we rarely saw the inside of the village kirk, but we knew the minister and the Bible he read from. The Catholic church – "the chapel", we called it – was a different matter. It had wooden sides and a corrugated iron roof and lay on the outskirts of the next village, where it had been built for migrant Irish workers at the beginning of the last century. On Sundays, our Catholic neighbours would put on their best clothes and walk over the hill to reach the hut's Latin ceremonies, which, when we occasionally heard them as passers-by, seemed to us superstitious and foreign. It wasn't a barrier to friendship. The regular attenders included two of my closest playmates, Patsy and Neal, and when we drew apart, the reason wasn't chapel, but Scotland's state educational system. Since 1918, it has funded separate Catholic schools where priests have full rights of access and the church can veto the appointment of any teacher on grounds of inadequate faith and character. The funding has always been contentious – "Rome on the rates" in the old catchphrase of its opponents – and the division gets much of the blame for Scotland's persistent sectarianism. But in a country where 16% of the population is nominally Catholic, no political party is likely to abolish it. For my Catholic friends it meant a complicated journey each morning to St Columba's in Cowdenbeath, the school that later recruited Keith O'Brien as a science teacher after his ordination in 1965. Separate buses meant separate departures and homecomings. We lost touch. In the long run of things, this hardly mattered. I made other friends who were Catholic or, more accurately in a post-religious age, friends who have "a Catholic heritage". None of the many questions that I expected would bedevil our conversations – papal infallibility, Irish state censorship, the Ne Temere decree and so on – ever gave us much trouble. And yet certain habits of mind endured. It had once been important to know who was and wasn't a Catholic, not in my case to deny them a job, but to avoid giving offence. In Glasgow, I worked on a newspaper where religious identities were layered like geology. On the editorial floor: mixed. Below in the composing room: mainly Protestant. Further below, in the machine room where the presses ran: substantially Catholic. There were careful conversations. "I hope you don't mind the question but are you a Catholic by any chance?" a subeditor colleague asked one night. No, but why might he think so? "Because you're wearing a shirt and no tie, but you've buttoned your top button. It's something I've noticed Catholics do." Sometimes the task of identification ran in the other direction. When another colleague was talking about Kirkcaldy, I mentioned the fact that my mother was from that town. "Your real mother?" he asked with a meaningful glance over his reading glasses, implying there were other kinds, perhaps (I could never be sure) in the form of Masonic lodges. The composing room had more direct methods. Compositors wanted to know which team you supported and when you said neither Rangers nor Celtic, that you were a Dunfermline or a Thistle man, a subsequent question arose: "No, but which team do you really support?" Of course, these questions conflated religious with ethnic identity: more than from theological dispute, they stemmed from Ireland's conquest and Irish migration. When Pope Benedict visited Scotland in 2010, his welcoming party was careful to stress Scotland's own pre-Reformation history and thus to nativise its Catholicism, but Scotland's Catholic population is of mostly Irish descent – O'Brien was born in County Antrim – with consequences not always predictable. My own grandmother, for example, liked to pronounce the republican De Valera as Devil Era, and detested the colour green so much that even the Christmas cards we sent her had to be green-free. But a form of denial may have been at work here, given the unknown but certainly Irish origins of her father and old stories that priests had once coming knocking at the family's door, anxious to reclaim their lost sheep. Who knew? And now, who cares? In the 1960s, the Catholic church still loomed large in the secular as well as Protestant imagination as an authoritarian and repressive force, demanding obedience from states and individuals, and interfering in everything from library books to birth control. Its doctrines may not have changed much, to judge by Cardinal O'Brien's beliefs, but these days fewer of us pay attention. Whether the accusations against him are true or false, the television still shows us pictures of elderly men decked out in primary colours imagining they matter. Majesty, history, mystery: these may have been the impressions they once conveyed, with their thrones, their curia and their white smoke. But now … well, one can't help thinking of the poor ashamed wizard when the curtain collapses in Oz. Our earlier suspicions were too ordinary: behind the drawn curtains, an occasional housekeeper fondled and a whisky bottle unstoppered. In truth, a vast male organisation pledged to celibacy was in a great sexual stew.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.