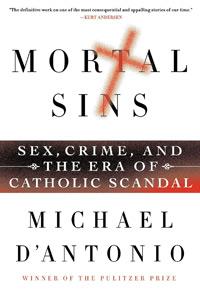

Mortal Sins Author Comes to S.B.

By Nick Welsh

After wallowing three years in the horrific minutia of the Roman Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal, writer and reporter Michael D’Antonio has emerged the unlikeliest of all things—a hardened optimist. D’Antonio’s latest book, Mortal Sins, reads like a courtroom thriller, but chronicles the real life tales of a handful of sex abuse victims who decided to take on the most enduring religious and political institution the planet has ever seen, the Catholic Church. “It took great courage for these people to come forward,” D’Antonio said. “In the face of enormous odds, they accomplished the impossible. I think the service they provided is profound.” Speaking of his own religious affiliation, D’Antonio commented, “I’m not a practicing anything, but I’m a big believer in the human spirit.” D’Antonio will be in Santa Barbara talking about his book next Friday, June 28, at the Faulkner Gallery of the downtown public library. Ray Higgins, a major player in Santa Barbara’s survivor community noticed that D’Antonio was coming to Southern California on a promotional tour and managed to snag him for the occasion. Higgins—whose son was molested by a Franciscan monk while attending St. Anthony’s—will be part of a panel of experts that will include Jeff Anderson, attorney from St. Paul Minnesota who has represented hundreds of victims who have sued the church; Patrick Wall, victims advocate and former Benedictine monk; Tim Hale, S.B. attorney who has represented many victims of clergy sex abuse. D’Antonio likened the movement against sex abuse within the church to the Arab Spring, a global human rights movement that he said has already had global impact. Mortal Sins begins in 1870 when the Vatican was effectively rendered “a moral empire,” by the re-unification of the Italian government then taking place. Its global influence since that time, D’Antonio said, rested soley on its moral credibility. And that, he said, has taken a massive hit in the wake of the sex abuse scandals beginning in the 1980s. “It used to be in Ireland that if you were five minutes late to Church on Sunday you couldn’t get a seat,” D’Antonio said. “Now the churches are almost empty.” Likewise, donations to the church throughout much of Europe have suffered dramatically. While there are countless tomes detailing various aspects of the scandal, D’Antonio provides the revelation that Fr. Thomas Doyle, a canon law expert assigned to the Vatican Embassy in Washington, D.C., began sounding the alarm within upper levels of the church as early as 1984 that the problem was vast. Triggered by one of the earliest sex abuse cases filed in the United States, Doyle—working with another priest and a church psychiatrist—conducted their own internal investigation. Two years later they delivered a copy of their white paper—complete with a series of recommendations—to every bishop in the United States. Some of the bishops, D’Antonio said, acknowledged there were problems. Most did not. Part of the problem, he said, is the intensely hierarchical nature of the church itself. Authority is not questioned; power is not shared especially with anyone not wearing a collar. If actual parents had ever been included in any of church panels reviewing such allegations, D’Antonio expressed confidence they’d have been acted on. In addition, there was abiding confusion within the church whether such sexual predations constituted a crime or a sin. If a crime occurs within the church “it’s still a crime, D’Antonio said. “It’s shocking today to see the extent to which this wasn’t understood back then.” One person who had no such confusion was Fr. Doyle. He was very clear and forceful. The church needed to take allegations seriously, treat those who’ve been wronged, and report the abusers to the proper authorities. To do otherwise, Doyle warned, would subject the church to massive legal liabilities. By D’Antonio’s estimate, the church has already paid out more than $3 billion in settlements. Doyle’s report went nowhere fast. Instead, the church circled the wagons, though increasingly to little end. Doyle might have been too blunt; but even had he been exceedingly politic, there would have been blow-back. “If you’re the only one saying, ‘Dammit, we’ve got to turn this thing around,’ and everyone else is saying, ‘We can manage it,’ you can see it’s going to be too much for them to accept,” explained D’Antonio. Doyle, for his pains, lost two prestigious posts within the church and now works on the outside providing expert testimony in court cases against the church. “When you have a priest standing with the victims, telling them that they’d been wronged, that can be very powerful,” D’Antonio said. Sexual abuse, as far as D’Antonio can tell, transcends time and space. It’s been a problem for decades and in every major city. It can’t be blamed—as some have tried—on adherents within the church of the liberal theological reforms in the 1960s. “It’s been a problem for every bishop whether they’re liberal, conservative, orthodox, or revolutionary,” he said. The issue blew up in the 1980s for a number of reasons. Social scientists had recently re-evaluated the issue and concluded that there was much greater validity to claims of sexual abuse than many medical experts had previously acknowledged. Talk show culture was just coming into its own with shows like Donahue and Oprah, where a premium was placed on open discussion of issues hitherto taboo. It was a show down of epic proportions, D’Antonio writes, pitting “American democracy against an ancient monarchy.” As victims began to come forward, judges had to take notice. Once a claim was filed and survived initial challenges, the victims were entitled by law to explore church documents and compel church officials to testify. The results have been damaging in the extreme. The hardest part of his research, D’Antonio said, was in talking to the victims who never healed. “It was hard hearing how these people had suffered and still suffer even though they’d been through the judicial process,” he said. “Justice doesn’t necessarily bring healing.” That’s why for D’Antonio, the real heroes of his book are the victims themselves. “It’s not easy to get up on the stand and talk about your weaknesses, to acknowledge you’d been molested.” And he’s quick to credit certain high profile attorneys who’ve taken their case, like James Anderson who received a glowing warts-and-all treatment. If nothing else, D’Antonio credits the early cases brought church victims of child abuse for opening the door for other victims. “If it wasn’t for them, I don’t think we’d be hearing all the complaints against the Boy Scouts and the various coaches.” D’Antonio said it’s hard to compare what kind of abuse is worse, adding there’s something particularly painful when a spiritual leader violates one’s trust as opposed to a Scout Master. Although D’Antonio is coming to Santa Barbara, he’s not exactly conversant with the details of the scandal that engulfed the Franciscans at St. Anthony’s seminary where at one time one out of every four brothers was a pedophile. Ray Higgins, who experienced a searing loss of faith from that ordeal, said he plans to bring him up to speed in the meantime. Over the years, spokespersons for the church—either the Franciscans themselves or the archdiocese as a whole—have insisted they’ve taken appropriate corrective action and as a result, no fresh sexual abuse cases are being filed. D’Antonio said he’s not in a position to judge which order have been most responsive, but expressed skepticism that even now the church is moving nearly fast enough. “After all this time, I’d be shocked to learn it’s as bad as it used to be,” he said. “But there were cases filed in the last year by individuals under the age of 18.” D’Antonio noted that for a thousand years, the Catholic Church ran the best global communication system on the planet. In that time, the church controlled a dominant flow of information. With the rise of the internet and world wide web the tables have turned. “Now someone in Milwaukee can post internal church documents online and share them with someone in California and someone else in Italy at the same time,” he said. “That’s fundamental. D’Antionio credited the sex abuse scandal as being one of the factors that pushed form Pope Benedict to resign last year. “He was tired and that was one of the major reasons that had tired him out.” The new pope, Francis could be promising, D’Antonio believes. It’s not uncommon for bishops throughout Latin America to have life partners whether they’re officially married or not. This tradition, he suggested, might make it more likely for Pope Francis to allow married priests. That, he said, was more likely than the ordination of women priests. In the meantime D’Antonio said, individual Catholics are re-defining their own relationship to their faith and the institution that represents that tradition. The church is not the hierarchy,” he said. “It’s not the bishops and the cardinals and the Pope. It’s the people. And increasingly the people are not loyal to the hierarchy and bureaucracy and to the leaders. But they remain loyal to their faith.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.