Playing Hardball against Women’s Rights: the Holy See at the Un

By Joanne Omang

During the Vatican conclave in March, while pundits in Rome spotlighted Pope Francis’s new-era penchant for buses and informal speech making, the old-era Vatican was hard at work at the United Nations, trying once again to take women’s rights out of the global dialogue. It failed, but was this a last attempt? Pope Francis, with his genial manner and his preference for the poor, has raised flutters of optimism among many Catholics hoping for a less arrogant and more modern church. That can’t happen too soon at the UN, where the Holy See has played serious hardball against women’s human rights for nearly 50 years. The New York Times called the latest example of the Holy See’s interference at the 53rd meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women an “unholy alliance.” Working with Iran, Russia and others, Holy See representatives tried to delete document language asserting that religion, custom and tradition are no excuse for allowing violence against women. The commission ultimately rejected this effort and the final document stands as a precedent against invoking any of these reasons to justify human rights abuse. The Holy See’s modus operandi has been to impose its conservative social ideology at the UN via relentless pressure—evident ever since it gained semi-official standing there in 1964. Pope Paul VI spelled out his privileged position at the UN the following year: his dual status as head of a church and head of state for the Holy See, he said, left him “independent of every worldly sovereignty” and made him the “bearer of a message for all mankind.” Nearly half a century later, the Roman Catholic church has global influence via the UN that is unique among the world’s religions. Only the Holy See and Palestine (since November 2012) hold Non-member State Permanent Observer status at the UN and most of its agencies. They have the right to speak, reply and circulate documents in the General Assembly, as well as take part in international conferences with “all the privileges of a state,” including the right to vote.

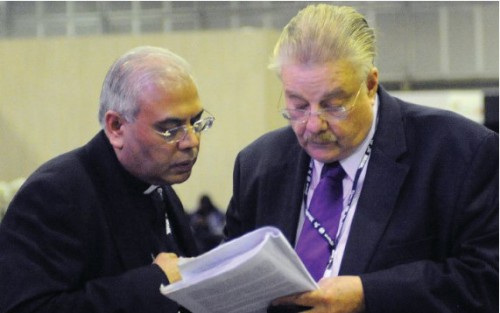

That means real power. Other religions or nongovernmental organizations must collar delegates in hallways and restrooms to make their points. Further, UN conferences operate by consensus. Every word, every punctuation mark of meeting “outcome documents” is negotiated among delegates from up to 180 countries in closed-door sessions—often acrimonious, agonizing gatherings that go late into the night. And, as many who have dealt with the Holy See know to their frustration, it’s all but impossible to negotiate with someone who claims to be voicing divine will. “They have their eyes on the prize,which is getting reproductive health off the global agenda,” said Alex Marshall,chief of UNFPA’s Services Branch, about his experience with the Holy See’s representatives. “They never stop, and they never give up.” Holy See delegates are legendary for their tireless attention to detail at UN conferences, resulting in long-term reverberations. Because they prolonged negotiations to such an extent that the closure of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) was delayed by five days, the definition of reproductive healthcare in the outcome document omitted abortion services. The European Union later endorsed the ICPD Programme of Action wholesale, without amendments, so that including abortion services in resulting programs now requires the reinsertion of abortion services every time. Score a few for the pope. Vatican emissaries routinely try to substitute women’s “dignity” for women’s “human rights” and to erase any reference to decision-making rights for adolescents. Pseudoscientific claims appear repeatedly in Holy See statements. Adrienne Germain, former president of the International Women’s Health Coalition, recalled in 2008 that the Holy See refused to endorse the use of condoms to prevent HIV at a 1999 gathering on the grounds that they are ineffective at blocking the virus. “I remember when people literally gasped” at that assertion, she said. In 1995, at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Holy See delegates objected to the word “gender” as code for “a broad feminist rights strategy that includes abortion.” Other false assertions include statements that women are victimized by rights-based reproductive healthcare, or that studies show abortion harms a woman’s mental health. More recently, the falsehood that “as a matter of scientific fact, a new human life begins at conception” was entered in the minutes of a 2011 General Assembly session. Other Vatican tactics are less subtle. Marshall recalled that in 1994, a Bolivian delegate to an ICPD preparatory meeting who was deemed insufficiently supportive of Vatican positions was “replaced with someone more compliant overnight, at the behest of the country’s nuncio”— the Holy See’s diplomatic representative to Bolivia. The conference chair refused to seat the replacement, but again, the failure didn’t faze the Holy See. Before the ICPD gathering, its secretary-general, Nafis Sadik, had an audience with Pope John Paul II, who “berated her for her unwillingness to steer the process in the right direction, as he saw it,” Marshall recalled in a 2010 Conscience article.

Of course, all NGOs and governments are expected to press their views on others i n order to w i n consensus. “There’d be absolutely no problem if the church was lobbying like other religions and other pressure groups,” said Jon O’Brien, president of Catholics for Choice. “But their privileged position gives them an ear of governments that they shouldn’t be able to have.” To states in which Catholic votes are critical such lobbying can be very persuasive. In 1994, the Vatican called in ambassadors from predominantly Catholic countries and lectured them on the proper positions on contraception and abortion to take at ICPD. John Paul II wrote to every head of state asserting that the ICPD draft would be a “serious setback for humanity” that would “condemn marriage to obsolescence.” His speeches called it “the snare of the devil.” “The church is very influential in Latin America, and things like that indicate ‘We’re not going to support you in the next election,’” said Serra Sippel, director of the Center for Health and Gender Equity (CHANGE) and a veteran of many battles over UN documents. The pressure can backfire, however, Sippel said. At 2004 conferences in Puerto Rico and Chile, Latin American delegates who had some reservations about reproductive health language “stepped up and owned it any way because they were so annoyed” by Holy See pressure. “They said ‘Hey, we agreed to the ICPD and you’re not going to come down here and tell us what positions to take on this,’” she recalled. Bene Madunagu, chair of the executive board at the Girls’ Power Initiative in Nigeria, was just as indignant. Bishops in Nigeria, she said, promote the status quo, “where talk about sex is taboo and talk about preventing unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases is forbidden.” In a statement to support Catholics for Choice’s initiative, The “See Change” Campaign, in 2000, she was blunt: “The role that the Roman Catholic church has played as an obstacle to AIDS education in Africa calls into question its moral right to a high status at the United Nations.” At the same time, Amparo Claro, director of the Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network, called it “entirely unacceptable that UN negotiations are influenced by exclusive and dogmatic ideologies and moralities permanently imposed on other members by a unique and privileged member.” The old-era Holy See ignores such protests and continues to tell governments what positions to take. Guatemala, Honduras, Ireland, Malta and Poland are reliable Vatican allies, among others. As early as 1994, special Vatican envoys went to Tehran and Tripoli to enlist their support—to “sup with the devil,” as Washington Post columnist Jim Hoagland put it—and alliances since then have included Iran and Libya as well as Syria, Egypt and other countries that do not support full human rights for women.

These countries got behind the Holy See’s efforts to exclude “forced pregnancy” from a list of war crimes proposed during the 1998 debate over setting up the International Criminal Court. They agreed that the Beijing Platform for Action did not express universal values but spoke only for disgruntled radical Western feminists. They have helped block efforts to extend human rights references to gays and lesbians, and at the 2012 Rio + 20 Conference on Sustainable Development fell in line behind the Holy See to exclude “sexual and reproductive” healthcare from areas of healthcare deserving particular attention in the outcome document. Some of the work opposing sexual and reproductive rights is accomplished by UN allies, with the Holy See preferring to remain behind the scenes. Conservative religious NGOs disrupted March 2000 preparatory meetings for Beijing + 5, surrounding opponents to pray over them, according to a 2001 Conscience article. At the ICPD, unofficial Arabic translations of draft documents were circulated that insinuated the phrase “sexual health” was equivalent to promiscuity. Vatican representatives “don’t need to put out documents when their allies do a lot of that work,” Sippel said. Marshall asserted that the new era for the Vatican may look very much like the old. “The new pope isn’t going to change that,” he said.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.