Hello and Goodbye – Review

By Claire Kilroy

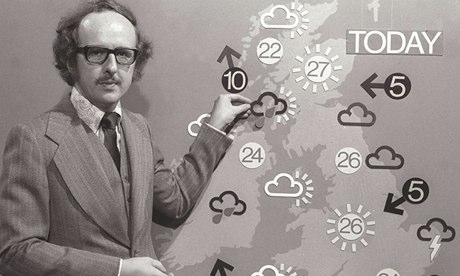

Published in a flip-over format, Hello and Goodbye is billed as two Halloween horrors in a single volume: Patrick McCabe does Patrick McCabre, if you will, for McCabe is a master of both the demented narrative and demented narrator. Beneath the ghosts and ghoulies, however, lies a compassionate exploration of the aftermath of psychological damage. The first novella, Hello Mr Bones, concerns a disgraced Christian Brother and an abused child. However – in a radical departure for Irish fiction – the abused child is the Christian Brother. As a boy, Valentine Shannon had been "interfered with" by the local psychopathic Anglo-Irish toff from the manor, "eccentric pervert" Balthazar Bowen, who styles himself as Mr Bones. Valentine goes on to join the Christian Brothers, only to be ejected after striking a student, one Martin Boan. In an effort to escape his past, he relocates to London and works as a lay teacher. His past, however, catches up with him when Valentine receives a phone call from Mr Bones. This call is even more disturbing than a call from one's abuser might usually be, given that Bowen, or Bohen, or Boan, or Mr Bones, is now dead. These days, Valentine is sustained by love. In his partner, Chris Taylor, a 70s feminist and lone parent, McCabe introduces another character who is something of a rare bird in Irish fiction: a good mother. Mr Bones, however, has designs on Chris's disabled son, Faisal, and repeated references are made to a horrific crime carried out on a boy with Down's Syndrome in Florida by a certain clown called Bonio who, by all accounts, is limbering up to strike again. The novella is set in 1987 on the day of the hurricane that assailed Britain. Michael Fish has reassured the populace that there is no need to worry, but in McCabeland, there is every need to worry. As the storm brews, Mr Bones's demonic plans reach fruition, leading to a chilling denouement. If the narrative voice of Mr Bones recalls that of another amoral Anglo-Irish murderer, John Banville's Freddie Montgomery from The Book of Evidence trilogy, the spirit of McCabe's second novella, Goodbye Mr Rat, is Samuel Beckett all the way: the main character is interred in an urn. Gabriel King has been cremated, though he hasn't let it stop him. His friend, Beni Banikin, from Indiana, is returning his ashes to his hometown, Iron Valley, in the border counties of Ireland. Beni believes her old friend Gabriel to have been a hero in the Irish Republican movement, who went on hunger strike in the Maze prison in 1981, a story Gabriel dined out on in the States. However – and yet again, McCabe tackles a topic that is rare in Irish fiction – repeated references are made to a sectarian attack carried out by Catholics on Protestants, a real crime in a little village called Altnavogue in which seven Protestants were murdered, one of them a baby into whose cradle a bomb was dropped. Gabriel expresses disgust and remorse from his urn, but his story changes as his narrative progresses. Can he be trusted? Similarly, his fellow IRA operatives are now respected elected public representatives, poachers-turned-gamekeepers. Their ringleader is mayor. Can they be trusted? Can anyone be trusted? Will the truth about the horrors of the dark decades of the Troubles ever come to light? Meanwhile, more damage is wreaked, this time on Beni, herself marked by a "sometimes shocking vulnerability" due to institutional abuse. When her unhealthy relationship with alcohol yields to the bacchanal of the harvest festival, and the word "bipolar" is thrown into the mix, we know we're in for another explosive climax. These are without doubt strange pieces, and they are strangely effective. How better to articulate the atrocities of the Troubles and the devastation of child abuse than through the horror genre? Hilary Mantel did it in Beyond Black, in which a rape victim, now a psychic by trade, literally lives with demons. Mantel didn't sanitise the aftermath of abuse, and nor does McCabe, for this isn't Alice Sebold's Lovely Bones, narrated from heaven and suffused with redemption. These are the Bones of Patrick McCabe: stark, fierce, and wonderful. • Claire Kilroy's The Devil I Know is published by Faber.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.