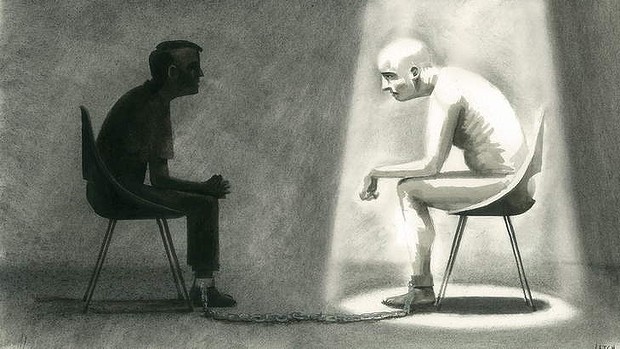

Try a New Approach on Sex Crimes and Justice

By Gay Alcorn

So fraught has any discussion of rape and sexual assault become, so enmeshed in gender politics, so prevalent - from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, to the Stephen Milne rape saga, even Julian Assange's refusal to travel to Sweden to face rape allegations - that it seems any crime involving a sexual element is highly charged. The reason why sex offences are so emotional is understandable given how we have grappled with them historically. The notion that rape was a property crime against a father or husband was not fully abandoned until marital rape was outlawed in Australia in the 1980s. Sexual offences are notoriously under-reported, and naming complainants would no doubt make that worse And whatever the law says, conversations in offices and pubs will still mention a woman's sobriety or short skirt if she later claims she was raped, particularly by someone she knows. The law has been reformed in the past 30 years, and the attitudes of the police and courts to victims transformed. Maximum jail sentences have increased, and the definitions of what constitutes rape changed, all to emphasise the seriousness of sex crimes and to make it easier for victims to seek justice. And none of it has budged conviction rates; the Office of Public Prosecutions says that just 45.1 per cent of all sex cases last year that went to trial led to a conviction, down from 54.8 per cent in 2004. There's no simple answer, but it's at least worth considering whether our continuing approach to sex offences - as somehow a crime apart, different from all others, with harsher penalties and shrill coverage - has had consequences never intended. And that gender politics, as essential as it is to understand sex crimes against women, can also mean refusing to acknowledge a crime's complexity - a complexity we have no trouble seeing in non-sexual crimes. The case of former magistrate Simon Cooper - who pleaded guilty in August to seven charges of indecently assaulting two brothers, both aged 17 or 18 at the time of the offences - at least avoids the overlay of gender politics, but it does highlight the increasing number of historical sex cases. The offences took place between 1984 and 1985, close to 30 years ago. It is exceptionally rare that police would prosecute an assault case if the victim didn't make a complaint for 20 or 30 years. But they do in sexual cases, even ones that are at the lower end of seriousness; a 2011 Victorian report noted a ''big increase in the number of historical cases'' in recent years. (Children delaying seeking legal help are entirely different; there is substantial research to explain why young children repress telling anyone about abuse for years or decades.) People who accuse others of crimes are named, but not those who claim sexual assault. Sexual offences are notoriously under-reported, and naming complainants would no doubt make that worse. Yet we are long past the era when rape was shameful because it cost a woman her virginity or damaged her marriage prospects or humiliated her husband. In some ways, our cultural attitudes to rape - from the deep-seated assumption that women routinely lie, to assuming that a victim must be deeply ashamed about what has happened and is unlikely to recover - undermine our intentions to grapple with these crimes. It doesn't seem entirely unfair that the two women who have accused Assange of rape, molestation and unlawful coercion should have been named on the internet. And it was hard not to feel sympathy for former state Labor minister Theo Theophanous, accused of raping a woman in Parliament House in 1998. The case was thrown out at the pre-trial committal stage, the magistrate describing the woman as an ''entirely unreliable witness''. She was never identified. Theophanous' career was destroyed. In the Cooper case, victim groups and even some politicians were outraged that he received a three-year suspended sentence, thereby avoiding jail. But if you read the full sentencing remarks, you might think Judge Stephen Norrish weighed up all the circumstances fairly, took into account Cooper's betrayal of the trust of a family that befriended him when he was a young barrister, the impact of his crimes on the older brother in particular and Cooper's remorse and assistance to police, as well as his public humiliation and the collapse of his outstanding career. The offences were tawdry and often alcohol-infused, but there was no penetration and no violence. One of the victims was interviewed last month on 3AW, and declined to join the chorus for vengeance. ''For me, it is [enough],'' he said of the sentence. ''A lot of people, I have no doubt, I know for a fact, ask the question, 'Why bring this up after so long?' I understand that question, I get it, and I'd say that those people are very fortunate because they've never had an experience of a sexual assault case or something similar in their family … I think bringing it up is the way of healing and talking about it.'' It was a compelling answer. He wanted his story acknowledged and believed. It may or may not have suited him, but there are some tentative suggestions for a different way to handling some cases. The Sunday Age this week reported an idea from senior judges and lawyers for ''restorative justice'' - to allow victims of some sex crimes, such as historic offences or incest, to meet their offenders in a controlled setting. They could ask for an explanation, and gain an apology or another form of reparation. It wouldn't be downgrading the seriousness of offences, but acknowledging that our black and white adversarial system isn't working for all cases. After all this time, all this failure, surely it's worth a try.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.