|

Francis’s Holy War

Matter

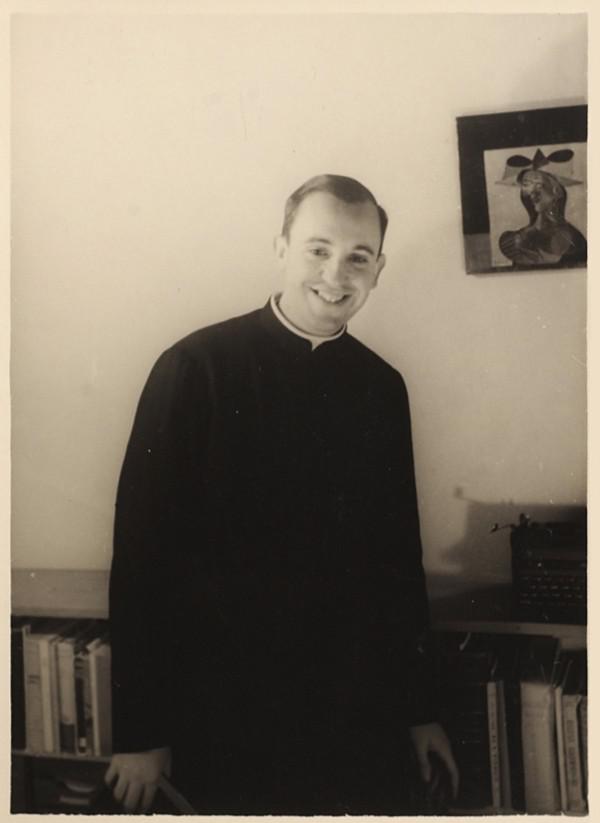

If you intend to be a proper Catholic priest, you would be wise to follow the little formalities of the church. When in Rome, for example, you are required to wear your cassock or at least a clergy shirt, and bishops and cardinals are expected to wear their flowing robes. But Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who was cardinal of Buenos Aires before he became known to the world as Pope Francis, hated pomp and ceremony and was not very proper at all. He kept his scarlet robes in a convent founded by an Argentine nun, so he wouldn’t have to carry the damn things back and forth to Vatican City. Before heading for a priests’ residence in central Rome he would stop by the convent, chat for a bit, and pick up the garments, which had been reverently pressed and folded for him by the nuns. Bergoglio stopped at the convent one last time, last year in March, on his way to the historic conclave of 115 cardinals that would elect him the first Latin American pope and the first from the order of the Society of Jesus—the Jesuits. He must have had a very good idea of his chances. Little known beyond Argentina, he had nevertheless finished second in the vote that elected Benedict XVI in 2005. It was understood that he was an outlier, ascetic, unconventional to a fault, but he seemed to be the right kind of pope to clean up the world’s oldest and largest institution, hemorrhaging followers and riddled as it is with ancient vices, and bring it into the XXIst century. What may not have been so clear to the cardinals who chose him above all others at that conclave is that Francis would enter the Vatican like Jesus into the Temple or a bull into a china shop, knocking over conventions and rules with abandon. And what stunned everyone was that, from the moment he stepped out on the balcony of St. Peter’s for the first time on that drizzly evening, he would channel a ravening hunger for change among millions of people all over the world. He certainly didn’t look like a world-changer. A mild-mannered, slightly stooped, grandfatherly old man dressed in simplest white—no lace and scarlet finery for him—he stood quietly contemplating the crowd for a very long minute before uttering a hearty buona sera! with a pronounced Argentine accent. The effort of bending forward to receive the people’s blessing made Francis’s back tremble slightly, and watching on a screen I, a non-Catholic, was moved, too. A few weeks later, on a plane coming back from Brazil, he uttered his famous “who am I to judge” gays, and things started to move very fast. What, really, can we make of this strange new pope? Hundreds of thousands of words have been written in the effort to understand him. He is without question the most popular human being alive today: Barack Obama gets an average of 1,300 retweets on his account; Pope Francis gets twenty thousand. Beyoncé, traveling from one city to another, fills an auditorium in each with twenty or forty-five thousand people. Francis, a 77-year-old who walks with a limp, has been filling St. Peter’s square every Wednesday morning with between eighty and a hundred thousand euphoric people. “Who cares what that old man says?” a worldly friend of mine said recently. Well, a jillion Catholics do, not to mention a large number of Palestinians and Israelis who looked on in astonishment as Francis, with a series of shockingly simple gestures, preached a wordless sermon of tolerance in the Middle East in May. Smiling, kissing babies, embracing beggars, donning a fan’s baseball cap, saying plain things in plain Italian, scoffing at his own church’s obsession with sex, the pope seems to us intimate and sensible, affectionate, neighborly, instantly readable, radiating warmth. Jorge Mario Bergoglio is, no doubt, all of these things, and also, sometimes, positively odd. He doesn’t take vacations. He’s terrible at languages. In the days following his election, he snuck out of the Vatican late at night to distribute alms among the homeless. He likes to imitate Christ, and he avails himself of random opportunities to engage in foot-washing, even though standard church practice is for priests and popes to wash the feet of twelve men of the faith—not women—only during Easter Week. But there are also earlier and more troubling stories from a lifetime ago, that in 1976, as head of the Argentine Jesuits, he ousted two of his radicalized left-wing priests from the order, leaving them with no protection against the searing repression that was getting started under the supervision of the country’s fanatical right-wing generals. The self-abaser who washes feet, the representative of Christ on earth who repeats earnestly that he is a sinner, the troubled autocrat who may indeed have committed a terrible sin, the beaming, fatherly pope who gives hope and spiritual sustenance to millions are one and the same person—a complicated man, conservative and radical, charitable and intransigent, a mass of contradictions. Eager to get the church back to its foundational years of poverty and evangelization, he’s made enormous changes already in everything from the way church finances are run to the renewed sense of purpose clergy now have in their lives. Always fearless, he has just boomed out a verbal excommunication of all members of the ’Ndrangheta, a particularly vicious global mafia organization based in Calabria. But a number of things stand in the way of his ambitious plans for the church’s future: his own character, which in the past has made him a divisive leader; the Vatican Curia, or government, beset with corruption and inefficiency; deeply conservative church hierarchies everywhere from Africa to the United States; and his health, which is far from good. This last month alone he cancelled two full days of appointments due to fatigue, and last week the Vatican announced that Francis would cancel his regular Wednesday audiences and daily morning masses through July. He has much to accomplish, and a larger mandate than any previous pope in memory to achieve his goals, but time and institutions stand in his way. One afternoon on the Borgo Pio—the Vatican neighborhood’s restaurant row—I talked late into the lunch hour with Jesuit Father Gabriel Ignacio Rodríguez, an intensely spiritual and friendly Colombian priest, about Francis, and his own feelings toward this startling pope. “Francis surprises me every day!” Rodríguez said, speaking in a hushed, churchy voice in the crowded restaurant, and managing the trick of exclaiming under his breath. He had been looking back to the “horrendous” years of Benedict XVI’s papacy, during which, whenever the church was in the news it was because of another financial scandal, or accusations of pedophilia against one more bishop, while the shy, elderly Benedict withdrew into his own rooms, increasingly aware that he was unfit to cope with the crisis. With the shock of Benedict’s resignation in February of last year came the sense of a church unmoored. “The only way I can explain the difference between that day—Benedict’s resignation—and what we have today is that God became present in the church,” he said. “Francis is a man who’s in the news every day because he surprises every day. Because he’s free, and human, and responds to the events of everyday life with an open heart.” “The way he interacts with people is clearly that of a Latin American man,” he added. “The kneeling everywhere, giving away rosaries, carrying the gospel around in his pocket—all of these are part of the religiosity of the people. It’s based on signs—symbols, gestures. European religion is more in the brain; more about discourse and categories. And then there’s the physical element. He needs contact. He arrives at a gathering looking worn, and in a few minutes he’s recharged through the contact with people.” Rodríguez leaned back in his chair, considering the joyful new sense of purpose that fills him and his brethren, the electrified crowds in St. Peter’s, the non-Catholic world’s enthusiasm. “If that isn’t God acting,” he exclaimed, out loud this time and with an enormous smile, “then tell me what it is!” I had the impression, as I made the Vatican rounds, that I was talking to men who hadn’t laughed in a while and were now relishing the opportunity. One afternoon I sat in the chic white office of Antonio Spadaro, who is the editor in chief of the influential Jesuit magazine Civiltà Cattolica. Last August, Francis chose the crisp, witty Spadaro as the interlocutor for his first lengthy interview, a text whose many ideas have been read, studied, and quoted in the Catholic world any number of times since. But what Spadaro wanted to talk about when we met was not the interview but the man. “The first time I met him, he gave me a hug,” Spadaro said of Francis. “And what was surprising was how comfortable it felt. The cercanía, the closeness, struck me. “People who knew him [before he was elected pope] say he was not always like this. He was more serious, withdrawn. Now he is more smiling, more expansive, as if he were more happy with himself. He has even gotten maybe a little bit fat, or not really fat.” Spadaro smiled affectionately and made a plump-y gesture with his hands. “Maybe more at ease.” Truly, one can look through hundreds of photos of Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Argentina and not find one in which he is smiling. Asked to define himself in the interview with Spadaro, Pope Francis answered, “I am a sinner,” and added, “It is not a figure of speech, a literary genre…. I am a sinner whom the Lord has looked upon.” Spadaro, who has clearly reflected intensely on every aspect of his meeting with Francis ever since (“He changed my life!” he says now) considered his subject: “There have been many crises in his life,” he said. “They are part of his personality. He has experienced suffering.” It was in 1973 when Bergoglio’s time of greatest suffering began. He was 36 years old and newly named as provincial superior, or national director, of the Argentine Jesuits. I was much younger than that and passing through Buenos Aires at the time, and clearly recall the collective political insanity of the period. The military, having deposed the populist leader Juan Domingo Perón years earlier, had just decided to allow him back. But the Peronist movement was split into a dozen factions, notably an ultranationalist far-right wing allied with sections of the putschist military, and an ultranationalist far-left wing spearheaded by a guerrilla organization, the Montoneros. The military set up clandestine torture centers and disappeared thousands of suspected guerrillas and their sympathizers. The guerrillas assassinated “class enemies” and set off bombs. Neighborhood priests became radicalized under the banner of the new, left-wing liberation theology (which claimed that the church should have “a preferential option for the poor”) or its Peronist variation, theology of the people (which shared that aim, but without liberation theology’s Marxist influence). Much of the church hierarchy collaborated openly and shamefully with the government torturers. Where was Jorge Bergoglio in all this? He was, at a minimum, sympathetic with a thuggish Peronist group called the Iron Guard, and eventually turned over administration of one of the Jesuits’ two universities in Buenos Aires to a few of its leading members. The historian Tulio Halperín Donghi remembered the group well: “It was a fairly sinister organization. In the [university] schools of the humanities, which were always the most political, these furies would suddenly appear, swinging chains,” he told me in a recent phone conversation. “It was completely crazy, because aside from everything else they were vegans, or something like that.” Bergoglio took his final vows in April 1973, as a member of the rigorous order of Jesuits, and barely three months later he was named provincial. He was too young, he says of that time now, but most of all he appears to have been far too inexperienced. During those years several radicalized Jesuit priests who worked in the shanty towns around Buenos Aires became trapped in a net of gossip and rumors against them, a net that their direct superior, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, may have helped to weave. The accusations centered on two men: the Hungarian-born Franz Jalics and the Argentine Orlando Yorio. Bergoglio, whose job as provincial it was to assign priests to their posts, kept telling the two priests that there was pressure from Rome to remove them from pastoral work. But he would not tell them why, or what the accusations were, according to a detailed account of the whole affair written by Yorio. The fact that Bergoglio was not only ideologically opposed to the activist priests but also younger—he had been their student—was no doubt a factor in the tensions between them. But the poisonous gossip that surrounded Yorio and Jalics wherever they went had to do with their politics, and especially with a general suspicion that Yorio was having an affair with one of the young women in the community and collaborating with the Montoneros.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.