Raped by His Supervisor Then Convicted of Buggery: Life in a 70s Boys" Home

By Helen Davidson

In 1972 a 16-year-old resident of a Sydney boys’ home was charged with buggery after he tried to report to his carers that he had been raped by a supervisor at work. Peter Solway says he was forced by the home’s administrator to lie to the police and confess to what was then a crime, or be transferred to a notoriously violent detention facility in Tamworth. As New South Wales moves to join Victoria in allowing people to have their convictions for homosexuality expunged, Solway’s story serves to show how the conviction is often only part of the story, and the bill only one step towards making amends for damaged lives. The NSW parliament will soon debate the private member’s bill from Liberal MP Bruce Notley-Smith, who is confident of it passing. Under the legislation, people charged with homosexuality will be able to apply for their conviction to be extinguished, provided the secretary is satisfied the other person involved was a consenting party. Homosexual acts weren’t decriminalised in NSW until 1984, and the age of consent for gay men remained at 18 until 2003. “We’re not quite sure how many [convicted] people there are out there,” Notley-Smith tells Guardian Australia. “You can’t easily pull these figures out, and many are not digitised. That’s why we’re making it that people apply to have their conviction extinguished rather than in one fell swoop extinguishing all convictions.” The Victorian government this year became the first state to introduce legislation expunging historical convictions, and expects to hear applications from next year. However until the processing begins it is unclear how complicated it will get, particularly with cases involving former wards of the state and victims of sexual abuse such as Solway.

In October 1971, aged 15, Solway was charged with being “uncontrollable” and sent to the Wright house at the Church of England Charlton boys’ home in the Sydney suburb of Ashfield, living alongside 19 other boys. At least two of the four Charlton homes are now believed to have been places of physical and sexual abuse of young boys, for which the governing body of the Sydney diocese of the Anglican church issued an official apology in 2004. Last year, 73-year-old, Albert John Abel, was sentenced to three years and four months in prison for attacking a 12-year-old boy he abused over several years at the Charlton home in Glebe. Solway tells Guardian Australia that soon after arriving at Ashfield he and other boys were taken by Charlton’s executive officer, Ray Menzies, on a camping trip to Sydney’s Blue Mountains. Solway says he witnessed Menzies sexually abusing a boy there. After about two months at the home, Solway landed a job in Stanmore, replacing another Charlton resident who Solway says he had witnessed being beaten by a houseparent because he was suspected of stealing. Solway says he was was raped three times by his supervisor at his job and threatened with the sack if he reported it. However, one Friday night a child welfare officer came to the home and the sole friend Solway had confided in convinced him to tell the officer, who took him into a room along with Menzies, his houseparent and another allegedly abusive teacher.

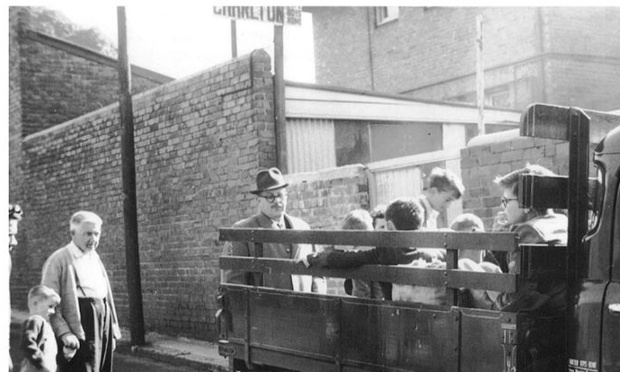

Solways says that upon hearing of his complaint about the rapes, Menzies threatened him. “I was shaking like a leaf, and Ray Menzies says to me ‘I’m going to send you to Tamworth boys’ home for this behaviour’,” recalls Solway. A detention facility for runaways from other boys’ homes, the Tamworth home has since been revealed as an extraordinarily violent place. At least 35 violent deaths have been linked to the the home, and an ABC investigation found a number of former detainees grew up to become some of Australia’s most notorious criminals and murderers. “I would meet kids when I was on remand, [who] had come down from Tamworth to go to a dentist or whatever, and you could see they were hardened,” Solways says. “I’m pleading with [Menzies], ‘please don’t send me there, I’ll do anything you want.’ ” Menzies sent him to the police and Solway was charged with “the abominable crime of buggery”. Police documents obtained by Guardian Australia state the perpetrator was also charged with the same crime in an adult court, and that Solway admitted to the act. “[Solway] was approached by the foreman and then during the course of employment the various acts of oral intercourse and buggery took place between them,” it reads. “This lad eventually became worried by his conscience and then he reported it to his housemaster at Charlton.” The documents also record that Solway told them he would like to stay at Charlton. Solway was held on remand at Yasmar boys’ home – another institution that has since faced allegations of abuse – until the case went to the children’s court. Charlton2.png Charlton boys’ home launches an appeal for funds in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1978. The ‘Peter’ referred to is not Peter Solway. Photograph: Sydney Morning Herald “I had to leave Yasmar holding prison and walk through rather large gates. My mother was there. I told her this was a set-up,” says Solway. “When the court asked her to stand and say something to support me her statement was: ‘Peter seems to be easily influenced.’ ” Solway was released back to Charlton on probation. In the following 18 months until he left the house, Solway says he was singled out by his houseparent and Menzies, with frequent jokes about his assault, as well as extra chores and physical and psychological punishments. Guardian Australia spoke to another former Charlton resident who says he was sexually abused by Menzies with increasing frequency over the years he lived there. “I ran away from Charlton twice – the second time I took off up to Katoomba,” the man, now in his 50s, tells Guardian Australia. “By Wednesday evening I got caught by the police. While sitting at the police station … I did happen to mention it to a desk sergeant. He said: ‘What do you expect, you’re in a boys’ home aren’t you?’ ” The man, who wished to remain anonymous, said he was currently in communication with Anglicare, the welfare arm of the Anglican church, and has told his story to the royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse in a private session, as has Solway. Solway received $75,000 as part of a “care and assistance package” after going through Anglicare’s redress scheme. In return he signed a deed of release, but Anglicare tells Guardian Australia that does not prevent a complainant sharing their story. Anglicare has received several complaints about Menzies, who is believed to have died in 2007, and at least one about the houseparent and the teacher, whose whereabouts are unknown. Andrew Forde, the director of pastoral care and mission development at Anglicare, does not know whether Menzies was ever questioned about the complaints. “When people come to us, particularly about Charlton, we have a fairly good idea that the perpetrators were there at particular times, and a fairly good idea now about the abhorrent things that happened at that time,” Forde says. “We accept care leavers’ stories pretty much at face value, and then work with them to acknowledge their story and work with them as much as we can providing counselling, walking alongside of them through a process of seeking some form of justice. “All of those things were abhorrent and should never have happened, and they’re particularly grievous when those who should be caring for these vulnerable young men, don’t just physically or sexually abuse them, but [take] coercive actions to intimidate on top of that,” he says.

Solway was unaware of the NSW legislation, but thinks he might apply if it passes. The associated abuse and stigma stayed with him long after he left Charlton. “You’re walking around and you get pulled over or picked up by police back then. I’d be with a couple of mates and they’d get on their radio to check out the charges,” he says. “And of course [that would lead to] ‘Oh we’ve got a ripe one here. Did you know your mate’s camp?’ It went on and on and on.” Solway got a job quickly and moved back to Lane Cove. “Then I picked up a drink of alcohol and never put one down till the age of 30. That’s how I coped,” he says. “I got to AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] at the age of 30, I was homicidal, suicidal, and my wife and I had just had our first child. I just couldn’t cope. So I found AA and I’ve been a member for 28 years.” Solway, now aged 58, says because of his “bad choice of lifestyle” he has hepatitis C, and has also suffered through kidney stones, Bell’s palsy, collapsed lung, renal failure and liver failure. He had a liver transplant in 2007, but then developed an addiction to pain medication. It took Solway two years to wean himself off it. “So I’m a survivor,” he says, “I’ve been tested. I survived it and I did that for my kids. I told my kids I’m going to try like hell to see it through. “I’ve been looking at all this … all this comes from my childhood, all of it,” he says.

“When you’re 15 your brain’s still growing, and when you put them into situations of trauma, you don’t develop properly. I missed out on adolescence, I never had boy-meets-girl, I never had any of that. That was all taken away. “I was robbed of all that.” On hearing Solway’s story, Notley-Smith said the buggery conviction was obviously one that should be extinguished. “If there is something in this bill that is an impediment to that, certainly we can amend the bill prior to it going to a vote,” he says. “One of the purposes of drafting a bill and then laying it on the table is that people from all sides can come along and say ‘I don’t fit into this category and yet I should.’ That’s certainly something I’ll be looking at.” Notley-Smith says the legislation is important because it will finally say “these people should never have been convicted, it was wrong”. “And to recognise the devastation it’s had on their lives, albeit very late in the day, we can correct some of the wrongs of the past.” Notley-Smith was 20 when homosexuality was decriminalised in the state. “Up until that time the feeling of insecurity and shame that is felt by knowing that you were potentially a criminal was quite devastating. Whilst I was never charged with anything, had I been I can just imagine how it would have completely altered my life. And I know that it did alter a number of people’s lives. Many, many people, and many of them are not with us any more.”

He would not be drawn on a potential formal apology, saying the focus for now was on the legislation. Solway’s case will be part of a submission delivered by the Care Leavers Australia Network (Clan), to the United Nations committee against torture in Geneva next year. Leonie Sheedy, the chief executive of Clan, called on all police commissioners and state governments to issue an apology to care leavers who tried to report their abuse when they were children. “Every child that ran away from an orphanage or foster home, they weren’t believed and they were put straight back into the hands of the abusers, no questions asked,” she tells Guardian Australia. For its part, NSW police does not have an available record of Solway’s case. In a statement, a spokesman says the force “encourages all victims of sexual assault to report their cases to police, no matter how long ago the assault may have occurred”. “The royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse has referred a number of matters to NSW police for investigation. The cases referred to police are being actively investigated, so no further comment can be provided at this stage,” he adds. The bill is expected to be debated when NSW parliament returns this month.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.