Moses, Solomon and the Monsignor

By Ralph Cipriano

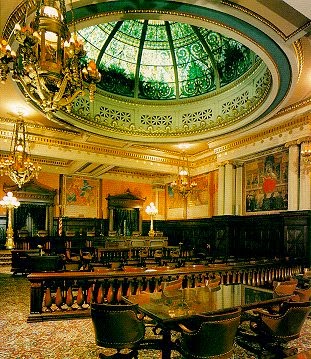

Under a stained glass dome and bronze statues of Moses and Solomon, the state's highest court this morning debated the fate of Msgr. William J. Lynn. "God save the Commonwealth and this honorable court," the court crier shouted in the packed, ornate chambers of the state Supreme Court on the fourth floor of the state Capitol in Harrisburg. Up at the raised mahogany bench, Chief Justice Ronald D. Castille got things rolling by announcing, "The issue here was this application of the [child] endangerment statute." That really is the issue in the Lynn case. The other justices, however, did not seem to want to stick to that script as they fired one extraneous shot after another at Thomas A. Bergstrom, the monsignor's defense lawyer. After it was over, Bergstrom had the dazed look of a hockey goalie. His adversary from the D.A.'s office seemed to get off much easier, but he did have to concede a few key points that could be fatal. Assistant District Attorney Hugh J. Burns Jr. chief of the Philadelphia D.A.'s appeals unit, was the leadoff speaker at today's oral arguments, which lasted less than an hour. In the Lynn case, Burns didn't have the law on his side so the fast-talking, heavyweight appeals specialist basically did some nimble tap dancing around the facts while tossing around phrases such as "legislative intent," "common-sense manner," and "accomplice liability." "Could you slow down a little bit?" Castille interrupted him. "You're going to overwhelm us with facts." That seemed to be the game plan as Burns attempted to paper over the facts of the case, which are pretty straight-forward. In 2005, former District Attorney Lynne Abraham and a grand jury looked at state's original 1972 child endangerment law and concluded it didn't apply to Msgr. Lynn, a supervisor of priests, rather than somebody who had direct contact with children, such as a parent or guardian. In 2007, Abraham led a statewide campaign to change the state's original child endangerment law to include supervisors with oversight of people who came into contact with children, supervisors such as Lynn. The state Legislature complied with the D.A.'s request by amending the state child endangerment law to include supervisors. In 2011, a new D.A., Seth Williams, decided without any official explanation to charge Lynn with child endangerment under the old state law, the same law that D.A. Abraham and the 2005 grand jury had said in writing didn't apply to Lynn. The state Superior Court saw the logic of this last December, when they tossed Lynn's conviction on child endangerment charges by saying -- drum roll please -- the original state law didn't apply to Lynn. D.A. Seth Williams appealed the reversal of Lynn's conviction to the state Supreme Court, and the Supremes decided to review the case. Without the law on his side, Burns launched a political broadside at Lynn that seemed to appeal to some justices. Lynn, the former secretary for clergy for the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, was responsible for investigating allegations of sexual impropriety against priests. But in making his argument, Burns gave Lynn more power than he actually had. "Instead of protecting children he [Lynn] protected priests by reassigning them," Burns charged. Under the original child endangerment law, Lynn may have not had direct oversight over children, Burns said, but by keeping track of abuser priests, Lynn was indirectly responsible for the welfare of children. So he should have kept problem priests like Edward V. Avery out of St. Jerome's parish in Northeast Philadelphia, Burns said, where Avery supposedly raped a 10-year-old altar boy named "Billy Doe." It sounded great unless you knew the facts of the case, which are that Lynn didn't have the authority to assign or reassign priests. In the imperial Philadelphia archdiocese, only the late Cardinal Anthony J. Bevilacqua had that kind of authority. But that didn't stop Burns from inventing his own story line. "He [Lynn] put Avery in a parish with children," Burns said. The monsignor, Burns said, was "guilty of accomplice liability." That's when Castille butted in and said under the law of accomplice liability Lynn "had to have knowledge" of what Avery was doing, didn't he? Burns had to admit that Lynn "didn't have knowledge of what Avery was doing." But the monsignor had to know he was "creating a danger to children" by putting Lynn in a parish with children, Burns argued. That appealed to Justice Debra Todd who asked Burns if it were true that Lynn was aware that Avery was continuing to moonlight as a disc jockey, a job where he had molested a previous victim. Burns was happy to answer that question in the affirmative. But Justice Thomas G. Saylor brought Burns back to the simple facts in the case when he asked if the state legislature's decision to amend the child endangerment law back in 2007 was a response to what the first grand jury had decided was a deficiency in the original law. It sure was, no matter how much further tap-dancing Burns did about the broad legislative intent of the original law. When it was Tom Bergstrom's chance to speak, the defense lawyer quoted the 2005 grand jury report that said that the original child endangerment law applied to people in close proximity to children, such as parents and guardians. The 2005 grand jury report concluded that the original child endangerment law did not apply to Lynn and other "high-ranking archdiocese officials," Bergstrom said, because they were "far removed from direct contact with children." In Pennsylvania, we have "35 years of precedent," Bergstrom said. The original child endangerment law was only applied to people with direct contact with children, such as parents or guardians. "Before you spin off," Justice Max Baer told Bergstrom, didn't Lynn assign Avery to St. Jerome's parish? "He did not," Bergstrom shot back. "Cardinal Bevilacqua assigned Avery to St. Jerome's." Bergstrom insisted that under the old state law, in order to be guilty of child endangerment, Lynn had to have "some involvement with the child." "He didn't even know this child existed," Bergstrom said of the alleged victim in the case. The justices wanted to know if Lynn supervised Avery. No, Bergstrom said. Why then is Lynn getting reports on Avery if he isn't Avery's supervisor, the justices wanted to know. It was up to Lynn to keep tabs on Avery, Bergstrom said, but when it came to the chain of command, Avery was under the supervision of the priests at St. Jerome's, and the officials at Nazareth Hospital, where Avery worked as a chaplain. In order to be guilty of child endangerment under the original state law, Lynn had to have direct contact with the child, Bergstrom argued. "He [Lynn] is not involved with a child," Bergstrom said. Lynn was secretary for clergy from 1992 to 2004. Billy Doe was allegedly sexually abused during the 1998-99 school year, but didn't report the abuse until 2009. Lynn "didn't know about it until he was charged," Bergstrom said. Chief Justice Castille thanked both lawyers for their arguments. We have your briefs, the chief justice said, and we'll be reading them. With that, the hearing was over. The court supposedly has some three months to make a decision on the case. []

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.