|

Globe reporters tell their ‘Spotlight’ stories

By Walter V. Robinson And Michael Rezendes And Sacha Pfeiffer

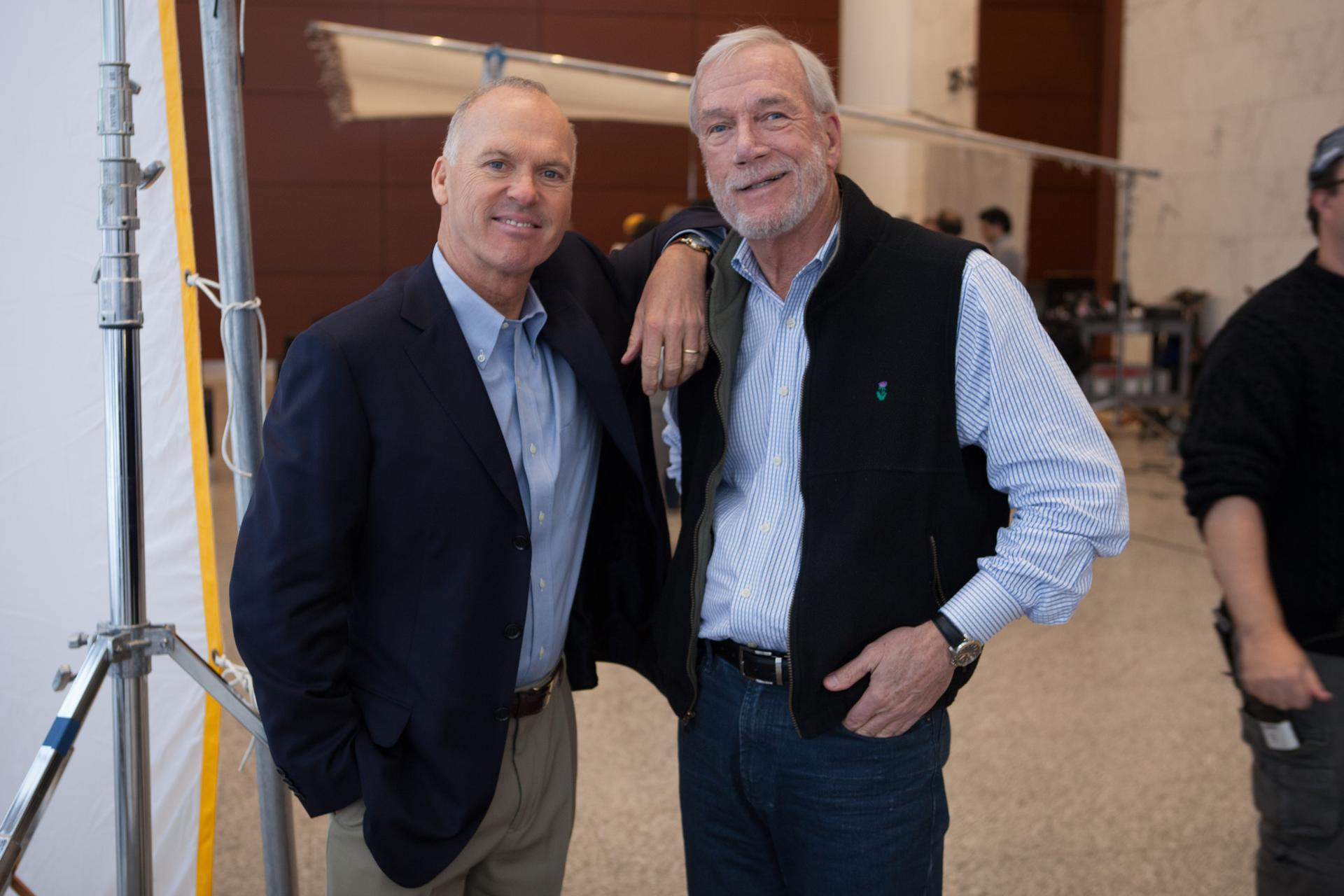

For months in late 2001, the Globe’s Spotlight Team chipped away in secret at a story that at first seemed unimaginable — that a succession of cardinals and bishops in the Boston Catholic Archdiocese had for decades covered up the sexual abuse of countless children by priests. In many cases, Church leaders took no action to deny their Roman-collared child molesters access to children. When the Globe began documenting the extensive abuse and the cover-up in January 2002, the story exploded, first in Boston, then nationally and in countries around the world. In the Boston Archdiocese alone, an estimated 200 priests abused children. Nationally, it is at least 7,000 priests. The escalating disclosures continue, and have shaken the very foundation of the Church. In September, director Tom McCarthy (“The Station Agent,” “Win Win”) and a cast of Hollywood names including Liev Schreiber, Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, and Stanley Tucci began shooting a movie titled “Spotlight,’’ about the Globe’s investigation. The filmmakers used locations in Boston and in Toronto, where they re-created the Globe newsroom and the Spotlight Team’s offices. With camerawork expected to wrap in the Bay State on Sunday, the film is scheduled for release late next year. For three members of that Spotlight Team — reporters Sacha Pfeiffer and Michael Rezendes and editor Walter V. Robinson — the movie is a constant reminder of the courage of the many victims of sexual abuse whose willingness to tell their stories in 2001 made the Globe’s investigative stories possible. And the film is also something else for those three journalists: It’s surreal. The “Spotlight” stars have all but assumed the identities of the characters they play, in ways the real reporters have found both humorous and, at times, a little unsettling. They share their experiences in Boston and Toronto. It was a familiar after-dinner parlor game, perhaps two decades ago: Who’d play us in a movie, we were asked. Lee Marvin would be me, I was told. Maybe James Coburn. Really, I thought. Why not Abe Vigoda? Fast forward to 2014: At least Abe is still alive. So there I am, last month in Toronto, in a near-perfect replica of my 2001 Globe Spotlight Team office. Michael Keaton is sitting at a copy of my desk, a two-fingered typist, just like me, his lips pursed, peering through reading glasses at a vintage 2001 Globe computer screen. Beside him on the desk? A framed photo of my real-life daughter, Jessica, taken in 2000. And beside that a framed photo of Michael — as me — with his arm around actress Elena Wohl, who plays my wife, Barbara. When art imitates life, Michael is a Vermeer among actors. He sounds eerily like me. He has expropriated my Boston accent, the one that comes and goes — whenevah. “Spotlight” director Tom McCarthy shouts, “Action,’’ and his voice dips an octave to match my base. My facial expressions, hand gestures, piercing look, arched eyebrow? They’re all his now. The way I sometimes — though not often, really — ask questions while lowering my voice rather than raising it? That’s now as much his modus operandi as mine. My persona has been hijacked. If Michael Keaton robbed a bank, the police would quickly have me in handcuffs. To watch Michael become me on film makes me want to apologize to many people I’ve interviewed: I never meant to frighten them into divulging anything, really. In one scene, Michael was even curtly dismissive of Rachel McAdams, who’s portraying my Spotlight colleague, Sacha Pfeiffer. Immediately, the real me texted the real Sacha to apologize. I first met my doppelgänger just after Labor Day in the bar at the Greenwich Hotel in New York. We shook hands. He gave me that gimlet-eyed, quizzical look I’d thought was mine alone. Before I’d uttered so much as a full sentence, he furrowed his brow, gave me a crooked smile — my smile — and said, “You know, you really don’t have that much of a Boston accent.” It was not a question. But how could he have known? He’d been tracking me, that’s how. He’d gotten hold of video and audio of past appearances I’d made on television news shows, C-Span and NPR. He’d been studying me. I was busted. During a long dinner that night, he was the reporter, I the subject. I chewed. He watched. I sipped. He peered. And he’s good at his new craft: Over several meetings since, Michael has extracted much too much information from me. Between scenes, he’s asked lots of questions: How would I have approached this subject or questioned another character? How deferential was I to senior editors? (Not nearly enough.) Initially, I was skeptical. First off, Michael looks a bit like my father, not me. Second, here is Hollywood making a film about Boston, and the first issue he raised is my accent. I knew where this was going. On the big screen, I was going to sound like a cross between JFK and Tom Menino. Wrong. The cast’s first get-together was the next day, after which I received a phone call. Michael, said my reliable eyewitness, “did a perfect impersonation of your voice.” When it comes to newspapering, this is not Michael’s first rodeo. People probably know him best for “Batman,” “Beetlejuice,” “Mr. Mom,” and now “Birdman.” My own fave is “The Paper,” in which he played a newspaper metro editor, in a pitch-perfect performance that real metro editors — including me at the time — raved about. What’s more, he’s a newspaper junkie who studied journalism in college. This is different: He’s playing me, not a fictional metro editor. It’s fascinating, of course, but also a bit bizarre. It’s like watching yourself in a mirror, yet having no control of the mirror image. This could go to my head. But on location, there’s plenty to bring me back to Earth. On the set, there are reminders, though sometimes confusing, about who’s who: When someone calls out “Robby,” my nickname, they mean Michael. And there is one of those raised director’s chairs, with the name “Robby Robinson” on it. That’s for him to sit in. My chair on the set? It says, “Guest.” When I found out Mark Ruffalo was going to play me in a movie based on the Globe Spotlight Team, I immediately flashed on the crazy quilt of characters he has played: the obsessed detective in “Zodiac,” the aw-shucks ladies’ man in “The Kids Are All Right,” and the washed-up record producer in “Begin Again,” to name just a few. So how was Mark going to play me circa 2001, when I was one of the reporters investigating the cover-up of clergy sexual abuse in the Boston Archdiocese? Pretty much exactly as I am — or was — it turns out. At first, watching Mark re-enact five months of my life was like looking into a funhouse mirror, as I slipped into a summer evening at Fenway Park more than a dozen years ago. There he was – or I was – with my short-cropped hair, blue button-down shirt, and black leather jacket, exactly as I would have appeared at a Red Sox game after work. But it was more than the wardrobe. After the fifth or sixth take of Mark taking guff from an older reporter and an editor, Mark introduced an odd, closed-mouth chuckle that I didn’t even know I used but which former Spotlight reporter Sacha Pfeiffer insisted was eerily accurate. “Oh my God,” Sacha said, grabbing my arm, as we watched the scene unfold one more time. “He’s got your laugh.” Weeks later in Toronto, where the movie makers had commandeered an old Sears building and rebuilt the Globe newsroom, it was very much the same. There was Mark at his desk in the ersatz Spotlight digs, spinning his chair around to yell into former Spotlight editor Walter V. Robinson’s office for a little banter, exactly as I had done virtually on a daily basis. It was, for me, like being rocketed back in time. But I should not have been surprised. When I met Mark for the first time at my home in Winthrop he quickly turned the tables, taking on my customary reporter’s role by whipping out a notebook and using his iPhone to record what turned out to be more of an interview than a conversation. Mark is as friendly and engaging as he often appears in his films but he’s also intensely devoted to his work. In this case, that devotion meant grilling me for hours about the ins and outs of reporting while trying to understand, as completely as possible, why I remain so dedicated to investigative reporting. The next day I met with Mark at the Globe, this time observing him as he observed me, another hall of mirrors experience. For starters, Mark shot video of me as I walked to my desk and settled in for a day of verbal combat. Then he sat with me and listened in as I worked the phone, trying to coax information from sources. Mark also had a chance to interview my colleagues and came up with a choice anecdote about how I’d recently raised my voice — turning up the volume more than a notch or two, it seems — while trying to get to the truth out of a suburban mayor who had totaled a city-owned car after an event where he’d been seen drinking. “Can I listen to you yell at someone?” reporter Mark Ruffalo inquired. It was the only time I politely declined to help him out. It wasn’t always pleasant to be rocketed back in time. For all of us who were on the Spotlight Team back in 2001, investigating clergy sexual abuse was a heart-breaking experience — and more hard work than any of us could have imagined. Each of us spent weeks interviewing victims, and I had heard more than a few stories I had tried to forget. And yet there was Mark, bringing it all back home. Mark’s research never seemed to stop. Whenever I was on set, it was not usual for him to seek me out to chat about a scene or ask me to repeat a line, or even just a word or two. During a break on that funhouse mirror evening at Fenway, Mark approached me for what I thought was going to be a friendly black-slapping moment. Instead, he leaned in close with an urgent request: “Hey, say this line for me.” During dinner at a downtown Boston restaurant, on an evening that was already feeling surreal — Rachel McAdams by my side, offering tastes of her branzino, Mark Ruffalo across from me, telling rip-roaring stories about his bartending days — Rachel leaned over and gestured to my right hand. “You’re wearing a ring you didn’t mention,” she whispered, with a tinge of surprise. I followed her glance to a small gold band on my pinky finger, a long-ago gift from a dear friend. Rachel was right: Weeks earlier, when she’d asked me what jewelry I wore in 2001, I’d forgotten about that tiny ring. And because she is trying to look, act, and even think like I did 13 years ago to play me in the upcoming “Spotlight” movie, the omission caught her eye. In this scrutiny-by-movie-star, no detail is too minute. Rachel has asked me how long I kept my fingernails. What size Post-it Notes I preferred. Whether I bought lunch at the Globe cafeteria or brought food from home. Did my husband and I ever cook together? (Yup, he’s a character in the movie, too.) What endearments did we use? Was there ever a time, while writing about priests who molested children, when I broke down? I’ve gotten used to texts from her arriving out of the blue: “Hey Sacha, random question: Do you remember what kind of shoes you wore around the office? (I know you had your trainers for your walks?) Did they usually have a heel or flat?” My answers have shaped the dialogue, props, and costumes for a Hollywood movie with an A-list cast. When I told Rachel that my late South Boston grandmother, who’s also a character in the film, was called “Nana,” not “Gran,” the writers changed the script. On set in Toronto, when I pointed out that my phone had been to the left of my computer, the crew redesigned my onscreen desk. Our initial contact was by e-mail. Its subject line — “from Rachel” — needed no last name. We set a date to talk by phone; that conversation lasted an hour and a half. Then we arranged to meet. She took a train to South Station, and as travelers came streaming off the platform I worried I wouldn’t be able to pick her out of the crowd. Suddenly, a peculiar realization: she had asked for photos of me from 2001 so she could have her hair cut and colored like mine. I shouldn’t be looking for Rachel McAdams; I should be looking for a replica of myself. By the time we met face-to-face, she had listened to taped conversations I’d had with director Tom McCarthy and screenwriter Josh Singer, watched videos of public appearances I’ve made, even tracked down interviews I’ve done more recently as a radio host. I talk quickly — a friend once said I “speak like a machine gun” — and Rachel told me she’d been working to mimic my rapid pace. Eventually, though, it was decided that if she spoke on screen like I do in real life, she’d be too fast for the audience to understand! She did, however, get to use my actual car: a 1995 Honda Civic. Its cameo in the movie came with a free paint job, leaving me with a 19-year-old diva that gleams like it just rolled off the dealer’s lot. Why capture the details from a decade ago so precisely? Here’s how Rachel explains it: When actors play fictional characters, “we’re usually making it up as we go along,” but when they portray real people — and “you’re my first,” she said — “it’s nice to have a solid foundation” to create an accurate “inner life.” “I totally think you’re allowed to take liberties,” she added, but “when I have the truth in front of me, I feel a responsibility to get you right and to find your essence.” You may be wondering if being channeled by a celebrity is going to my head. I’ll simply note that when a British newspaper obtained photos of Rachel filming a scene in which she nailed my look — loose untucked shirt, practical black shoes, even the natural wave in my hair — it eviscerated her appearance as only a London tabloid can. “Rachel McAdams Dresses Down For Role As Investigative Journalist,” the story crowed, citing her “messy tresses,” “clunky” loafers, and “baggy clothes.” Dressed as I did in my late 20s, the actress was pronounced “hardly her red-carpet-ready self.” Contact: walter.robinson@gobe.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.