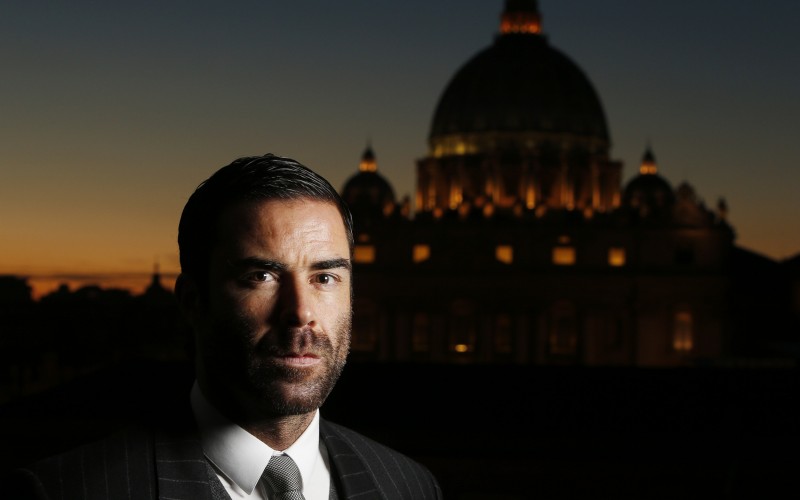

The Days of Ripping off the Vatican Are over

By Cardinal George Pell

In an exclusive article Cardinal George Pell explains his mission to sort out the Vatican's finances Recently a young Spanish lad asked me to explain the nature of my work in the Vatican as prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy, as well as the past and present economic situation of the Holy See. Why? Because as a member of Opus Dei and a first-year university student, he wanted to be able to answer the questions of his fellow students and defend the Church. A member of a British parliamentary delegation put it in a somewhat different way: why did the authorities allow the situation to lurch along, disregarding modern accounting standards, for so many decades? In reply, I began by remarking that his question was one of the first that would come to our minds as English-speakers (lumped together by the rest of the world as “Anglos”), but one that might be much lower on the list for people in another culture, such as the Italians. Those in the Curia were following long-established patterns. Just as kings had allowed their regional rulers, princes or governors an almost free hand, provided they balanced their books, so too did the popes with the curial cardinals (as they still do with diocesan bishops). Because of the size of the Catholic community, with about 3,000 dioceses spread through every continent, the principle of subsidiarity – that is, local management of diocesan and religious order finances – is the only option. The responsibilities of the Secretariat for the Economy are limited to the Holy See, Vatican City State and the almost 200 entities directly answerable to the Vatican. But already some cardinals and bishops have wondered aloud whether the new set of financial procedures and chart of accounts, introduced in November this year in the Vatican, might be sent to bishops’ conferences for consideration and use. This is something for the future. It is important to point out that the Vatican is not broke. Apart from the pension fund, which needs to be strengthened for the demands on it in 15 or 20 years, the Holy See is paying its way, while possessing substantial assets and investments. In fact, we have discovered that the situation is much healthier than it seemed, because some hundreds of millions of euros were tucked away in particular sectional accounts and did not appear on the balance sheet. It is another question, impossible to answer, whether the Vatican should have much larger reserves. I once read that Pope Leo XIII sent an apostolic visitor to Ireland to report on the Catholic Church there. On his return, the Holy Father’s first question was: “How did you find the Irish bishops?” The visitor replied that he could not find any bishops, but only 25 popes. So it was with the Vatican finances. Congregations, Councils and, especially, the Secretariat of State enjoyed and defended a healthy independence. Problems were kept “in house” (as was the custom in most institutions, secular and religious, until recently). Very few were tempted to tell the outside world what was happening, except when they needed extra help. Many will remember the scandals at the Vatican bank (IOR) in the early 1980s, with Archbishop Paul Marcinkus and the lay bankers Michele Sindona and Roberto Calvi (who was famously found hanged under Blackfriars Bridge), and the Vatican being constrained to pay $406 million (?259 million) in compensation. Comparative quiet then returned, until the international laws against money laundering needed to be applied within the Vatican. The authorities supervising the Vatican bank did not move swiftly enough, and some tens of millions of euros were frozen by the Bank of Italy, with many European banks refusing to deal with the Vatican. It was a grave situation where the worst was narrowly averted. It was only this November, after years of dialogue and good work, that the ˆ23 million (?18.3 million) were released. A major factor in this normalisation was the establishment of the Financial Information Authority (AIF) within the Vatican, an agency, like those in every Western country, dedicated to preventing and eradicating money laundering. The Swiss layman Rene Brulhart has just become the first lay chairman of the AIF. Its board principally comprises international (lay) experts. Irregularities or suspected crimes are referred to the Vatican authorities when they occur within the Vatican and are reported to other national authorities, such as Italy, when appropriate. When we return to the last years of Benedict XVI’s pontificate, we find that troubles had returned to the Vatican bank. The bank’s director, Dr Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, was sacked by the lay board and a power struggle in the Vatican resulted in the regular leaking of information. The scandal exploded when Paolo Gabriele, the papal butler, released thousands of pages of photocopied private Vatican documents to the press. My first reaction was to ask how a butler could have enjoyed any access, much less regular access for years, to sensitive documents. Part of the answer is that he shared a large undivided office with the two papal secretaries. All of this was severely damaging to the reputation of the Holy See and a heavy cross for Pope Benedict, who asked three distinguished retired cardinals to investigate the situation. They did so, presenting Benedict XVI with a confidential report. He then gave it to his successor, Pope Francis, after his decision to resign – the first such resignation since that of Pope Celestine in 1294. In the pre-conclave meetings before the election of Pope Francis there was an almost unanimous consensus among the cardinals that the curial and banking worlds in the Vatican needed to be reformed and normalised. Since his election Pope Francis has explicitly endorsed the programme of financial reforms, which are well under way and already past the point where it would be possible to return to the “bad old days”. Much remains to be done, but the primary structural reforms are in place. When Pope Francis realised that the Vatican financial systems had evolved in such a way that it was impossible for anyone to know accurately what was going on overall, he appointed an international body of lay experts to examine the situation and propose a reform programme. The group came to be known as the Organisation for the Economic-Administrative Structure of the Holy See (COSEA) and was led by Joseph Zahra, a senior Maltese banker. Senior executives charged nothing for their services, met regularly over 10 months and put together the reform package which is being implemented now. For generations to come, the Church will be very much in their debt. Three basic principles lay at the heart of their work. They are not original – and not exactly rocket science. The first principle was that the Vatican should adopt contemporary international financial standards, much as the rest of the world does. Until recently, the Vatican had no prescribed standard accounting procedures. The second principle meant that Vatican policies and procedures would be transparent, with financial reporting broadly similar to that of other countries, and the consolidated annual financial statements would be reviewed by one of the Big Four audit firms. The third important principle within the Vatican was that there should be something akin to a separation of powers and that within the financial sector there would be multiple sources of authority. These organisations would be coordinated, but would each have senior expert international lay leadership exercising substantial control. The budgets of individual congregations and councils would be approved, and their costs controlled against these budgets during the year. But each of these bodies would be responsible for its expenditure and penalised in the following year if overruns occur. On February 24, Pope Francis set up the Secretariat for the Economy, which has authority over all economic and administrative activities. It no longer reports to the Secretariat of State, but directly to the Pope. This represents a substantial division of authority. Equally new is the fact that the Secretariat implements the policies determined by the Council for the Economy, which has eight cardinal or bishop members and seven high-level lay members, all from different nations. The lay members are not advisers but have equal voting rights with the cardinals (one person, one vote). Having decision-making lay members at this level is an innovation in the Vatican. Neither the Secretary of State nor myself, as prefect for the Economy, is a member of the Council, whose role is similar to that of a university senate or council in the English-speaking world, where the vice-chancellor has to persuade the senate of the wisdom of his recommendations. The IOR will continue to be governed by an expert lay board, set up by a commission of cardinals, but will not technically be the Vatican bank as it will deal with money from dioceses, religious orders and Vatican employees. The Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See (APSA) will become the treasury of the Vatican. It will continue to link up and liaise with central banks, such as the Bank of England. Eventually, all investments will be made through Vatican Asset Management, controlled by an expert committee, which will offer a range of ethical investment options, with varying degrees of risk and return, to be chosen by individual agencies such as Congregations. Prudence will be the first priority, rather then risky high returns, in order to avoid excessive losses in times of turbulence. In the New Year an auditor general will be appointed, answerable to the Holy Father, but autonomous and able to conduct audits of any agency of the Holy See at any time. The auditor general will be a lay person. These reforms are designed to make all Vatican financial agencies boringly successful, so that they do not merit much press attention. Such ambitions cannot ensure that we will not find some static on the lines in the next year or so. But we are heading in the right direction. A German princess once told me that many used to think of the Vatican as being like an old noble family slowly sliding towards bankruptcy. They were expected to be incompetent, extravagant and easy pickings for thieves. Already this misapprehension is dissolving. Donors expect their gifts to be handled efficiently and honestly, so that the best returns are achieved to finance the works of the Church, especially those aimed at preaching the Gospel and helping the poor escape from poverty. A Church for the poor should not be poorly managed. Recently a senior delegation from the United States, mainly Evangelicals, came to discuss our work. One finished up by explaining that he was praying for the success of the financial reforms, because he wanted the Vatican to be a model for the world, not a source of scandal. This is our aim too.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.