|

Of two minds on economics: Does teaching at Creighton institute contradict Catholic social thought?

By Steve Jordon

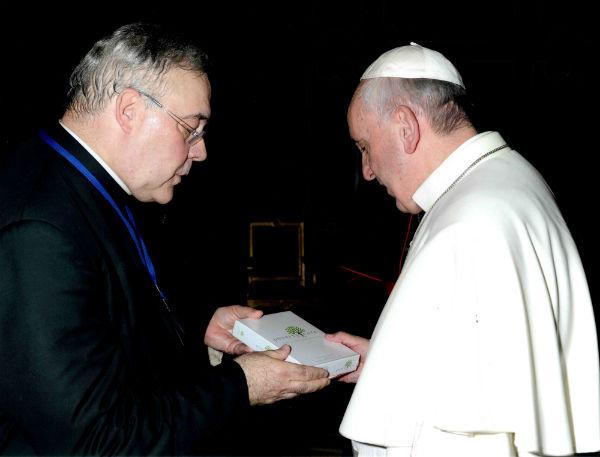

Creighton University is now part of a loosely connected but growing network of U.S. universities with economic teaching and research funded, in part, by Charles Koch, the Kansas billionaire and backer of conservative candidates and causes. Critics of the new Institute for Economic Inquiry say it favors a brand of economics that contradicts long-established Catholic social thought, endorsed by Pope Francis and his predecessors. One Omaha priest accuses the Charles Koch Foundation of pushing its ideas “to the very doorstep of the Vatican.” The institute is funded 50-50 by pledges totaling $4.5 million over five years by the Charles Koch Foundation and the family of Omaha trucking entrepreneur C.L. Werner. Gail Werner-Robertson said she approached the university, her alma mater, last year about a new economics program because she thinks too few college students, including her own children, get information about the different economic systems at work in the world. “I’m fascinated with the history of many things, but particularly economics and why different countries have different levels of prosperity,” she told The World-Herald. “We are the most blessed country on the face of the earth. ... It’s really been a passion of mine: What do we have different that maybe other countries don’t have?” Among the institute’s other supporters are Creighton’s president, the Rev. Timothy Lannon, who told The World-Herald that the university’s Heider College of Business is “a good home” for the institute and that he recognizes the disagreements it can raise regarding economics, politics and even religious principles. “There’s a tension there, about the role of the government and what it should do about the human community,” Lannon said. “What better conversation to have than about the impact that different economic models have on the well-being of the human community?” But others, both inside and outside Creighton, say a Koch-influenced view of economics and politics is tainted by the reputation of the Koch family’s businesses and is at odds with Catholic social thought, including the recently expressed ideas of Pope Francis. In a report sent to the Vatican, the Rev. Clifford Stevens, senior pastor in residence at Boys Town, said the Creighton institute is part of a Koch-supported campaign to “unseat Pope Francis as the moral voice of Catholicism ... by a band of nominal Catholics whose devotion to free market economics is almost religious.” Instead of viewing economic activity and wealth as a means to advance the common good of society, as Catholicism has taught for generations, the institute comes from a school of economic thought — considered mainstream among U.S. universities — that says people’s economic decisions are based on self-interest, although benefits to others may follow. Creighton Business Dean Anthony Hendrickson said the institute’s added faculty positions will help the college keep its 20-1 student-teacher ratio as it grows, from 650 undergraduates two years ago to nearly 900 today. Beyond that, he said, a campus should have “a lively discourse on issues, especially in the area of economics. I think this is the type of thing that has to happen if you have a good university.” Creighton’s Jesuit tradition allows viewpoints that aren’t shared by everyone, Hendrickson said. “We don’t want our students to be indoctrinated. ...We want to present all ideas and teach students how to think critically and let them come to their own conclusions.” Creighton theologian Thomas Kelly said he is not opposed to wide-open discussion, but he’s not sure institute officials are interested in doing that. “They’re just kind of doing their things.” Proponents of free market economics, he said, characterize traditional Catholic social teaching as “wishful thinking” because of what they see as an unrealistic belief that people make economic choices with the common good in mind. That economic viewpoint is “extreme” in its opposition to Catholic social thought, Kelly said. “It is inconsistent with who we are in a Catholic university. They essentially take starting points and take positions that really disagree with our heritage.” In addition, he said, there was no advance discussion about accepting money from the Koch Foundation. “It’s been disturbing for many of us on the arts and sciences side to sort of see that the money came in without any debate campuswide. We would have never accepted pro-choice money, yet we accept the Austrian school of economics money. In terms of what kind of society do we have, it’s certainly not one committed to the common good.” The Creighton Institute hired economists Michael and Diana Thomas, husband and wife, from Utah State University, which has Koch financial backing. Their doctorates are from George Mason University, where Charles Koch is on the board of an economics think tank. George Mason University has received about $30 million in Koch Foundation money in recent years. Werner-Robertson said that when the business college embraced the idea of the institute, she and her father and her husband, Scott, pledged half the money and worked with the Koch Foundation to pledge the other half. In 2005, the family had funded the Werner Institute for Alternative Dispute Resolution at the Creighton Law School, where Werner-Robertson earned a law degree. She said she knew Charles Koch had supported economic studies at other universities, had met him and was aware of some of his views, which matched hers. Koch (pronounced “coke”) is CEO of Koch Industries, a petroleum-led conglomerate that is the second-biggest privately owned company in the nation, behind Cargill Inc. His brother, David, also a company officer, is founder of Americans for Prosperity, a political group that backs conservative political candidates, including Nebraska Gov.-elect Pete Ricketts. Charles Koch is a student of economic history, Werner-Robertson said. “He’s an amazing fountain of knowledge. He has studied this since he was in his 20s and now he’s in his early 80s. He’s spent a lot of time learning these theories. I was fascinated about how this could be brought to Creighton.” Werner-Robertson’s vision was that the institute would expose students to a wide range of economic thought, and that has happened in its first semester, she said, partly through an evening reading group. Its 10 students meet with Michael Thomas and review a varied list of economic writings. “The students are really bright. They come prepared and ready to discuss,” said Werner-Robertson, who has attended two of the group’s sessions. Thomas said a similar reading group, organized by other professors, was successful at Utah State. As at Utah State, the students in the noncredit reading group receive a stipend — $200 if they attend at least eight of the 10 sessions this semester, plus about $75 worth of books. The institute also pays students an hourly wage for research projects they carry out during the year. Topics so far include how government regulation affects the Uber and Lyft shared-ride business and how politics is influencing the debate over Internet neutrality, a pair of issues that fall in line with the Thomases’ field of study known as public choice. (Its adherents also assume that individuals make economic and political choices based on their self-interest.) At the core of some concerns about the new institute is whether the Koch Foundation will influence the curriculum and research at the institute or its recruitment and hiring of faculty members. In 2011, a Koch Foundation grant agreement at Florida State University calling for an advisory committee appointed by the foundation to recommend faculty candidates was roundly criticized as a violation of academic freedom. There’s no such requirement at Creighton, said John Hardin, director of university relations for the Charles Koch Foundation. The foundation’s grant guidelines specifically say faculty hiring, research subjects, teaching practices and other academic matters are strictly up to each of the 250-plus universities receiving grants. (That’s up from about 150 universities in 2011.) The mission of the Creighton institute, Hardin told The World-Herald, “aligns very closely with our mission. We are very interested in supporting opportunities for scholars to dig into questions about the institutions, the ideas, the conditions that enable our society to be better off or to offer opportunities for everyone to improve their well-being.” He said there is a “total disconnect” between the foundation and Koch Industries, and concerns about Koch Industries should be directed to Koch Industries, not the foundation. The University of Nebraska at Omaha received about $10,000 a year from the foundation for five years to hire replacement teachers so that economist Arthur Diamond Jr. could develop new seminar courses for graduate and advanced undergraduate students. Diamond said he also has received grants from a group funded by George Soros, a left-leaning businessman, and that such support helps advance his teaching, research and publications in economics. The Koch connections have raised concerns among faculty members, said Roger Bergman, a sociologist and anthropologist and director of Creighton’s Justice and Peace Studies Program. The institute’s first campuswide event was a Nov. 12 speech by the Rev. Robert Sirico, a parish priest from Michigan who also is director of the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty, a think tank funded in part by the Koch Foundation. He wrote a book, “Defending the Free Market,” that is on the reading list of the institute’s student reading group. The Acton Institute has an office in Rome and has won some high-ranking church officials to its economic viewpoint. Its website has a photo of Sirico handing the pope a copy of the “PovertyCure” DVD series, which advocates encouraging entrepreneurs as a mean of fighting poverty. Bergman said when Sirico during his speech implied that the Catholic church is discarding “liberation theology” — a long-held Catholic idea that the teachings of Jesus call for liberating the poor from unjust economic, political and social conditions — “I could feel my blood pressure going up. That’s intellectually irresponsible.” Bergman, who challenged Sirico’s statement about liberation theology during a Q&A period after the speech, said in a later interview that having Sirico as the institute’s first speaker was a sign that the institute would ignore traditional Catholic thought on government’s role in regulating business and helping the poor. “There are concerns that the work of this institute would be directed by the Koch brothers,” Bergman said. “They say no, not at all, yet the first person they bring in is not an academician and is an advocate of libertarian economics, what they call Austrian economics,” from a Koch-backed group. Many faculty members in the college are keeping an eye on the new institute. “As long as we have the opportunity to include all viewpoints, it’s a good thing,” said Thomas Purcell III, an accounting and law professor. Andrew Gustafson, an ethics and society professor, said the Thomases are “good with the students. They’re good at raising dynamic discussions. I have not found them to be ideological.” Ernie Goss, a longtime Creighton economist and director of the new institute, said he was asked at a faculty meeting whether it would bring in speakers with opposing viewpoints. “Probably,” Goss told The World-Herald. “But nobody asked the Center for Health Policy & Ethics if they’ll bring in somebody from the other side, or the Justice and Peace Studies Program if they’ll speak for the other side by having somebody in. “We will have some venues where we’ll have a panel that will speak to issues. I’m not sure what the other side is, if we’re defending free markets. Is the other side defending Marxism? I don’t know that we’re required to bring in somebody to defend Marxism.” He said some faculty members with different viewpoints have turned down invitations from the institute. The institute co-sponsored a panel discussion Friday with Esther George, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Goss said he more or less shares the views of Charles Koch that markets should not be unduly restricted by regulation and that capitalism is the best system for improving everyone’s standard of living. He said he thinks there’s concern that nationally on college campuses, there are not enough voices of “those who believe that the freer market provides more support for those who are less well-endowed, the poor.” Lannon, Creighton’s president, questioned the idea of a litmus test for donations. Quoting Pope Francis, he said, “Who am I to judge? ... It’s really dangerous to judge people’s backgrounds in deciding whether to receive a donation.” He said the Koch-Werner grant will provide valuable economic instruction for students and worthwhile research. In his three years at Creighton, Lannon has rejected one donation, a $500,000 offer that had “strings attached that I could not accept.” Creighton also accepts scholarship money from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which advocates birth control in Third World countries, a position contrary to church teaching. “Should we not accept the funding that allows poor students to attend Creighton? If you have a litmus test of some sort, it gets pretty dicey.” Institute faculty member Diana Thomas said she’s aware of campus concerns about influence by the Koch Foundation. “Everything I’ve done in my career has been independent from the funding source,” she said. “Nobody has ever told me to do anything or not.” She said faculty members in the economics department “kind of agree on economics. All of us are mainstream economists.” She doesn’t consider herself political, a Republican or a Democrat. Last summer, she worked on efforts to encourage the State of Nebraska to issue driver’s licenses to immigrants who were brought to the United States illegally as children but have obtained federal permits that allow them to work. Thomas said denying driver’s licenses is “economically wrong” because it makes employment difficult for people otherwise qualified for jobs. The American Civil Liberties Union, usually considered a liberal organization, supports the licensing effort. But Thomas’ studies and research also have led her to a conservative position on government’s role in the economy. Last year she co-authored a Washington Times article titled “Antitrust Busybodies” that criticized federal handling of the merger of American Airlines and US Airways. “Antitrust law enforcement decisions are vulnerable to the influence of special-interest groups, as we recently documented in a Cato Institute policy analysis,” the article said, referring to the libertarian think tank founded in 1974 by the Charles Koch Foundation. Thomas introduced Sirico at his campus speech. “The whole point was choosing somebody who would engage the whole campus,” Thomas said. “He’s interested in the same problems. We thought that was a good choice for the first speaker. But unfortunately that didn’t seem to be true.” She said she hopes the discussion about economics will continue. “Academia is all about dialogue and having conversations and figuring out what the right situations are,” she said. “... I think it’s all about figuring out what the right answers to the wider questions are. That can only happen when you talk to people who have different perspectives.” Thomas said part of Creighton’s attraction for the couple was that they are both Catholics. “The original question that economists have been trying to answer is, how do we make people better off? What economic system solves problems and allocates resources so that people are the most benefited? “I can’t imagine that would be in conflict with Catholic social teaching.” Contact: steve.jordon@owh.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.